Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

THE GATWICK/HEATHROW AIRLINK

– recollections by Captain Bill Ashpole FRAeS– Manager & Chief Pilot – with contributions by others including named individuals* who played vital parts in the establishment and operation of this unique service *especially Laurie Price (who provided much of the introduction of this article), Betty Wells and Frances Thompson

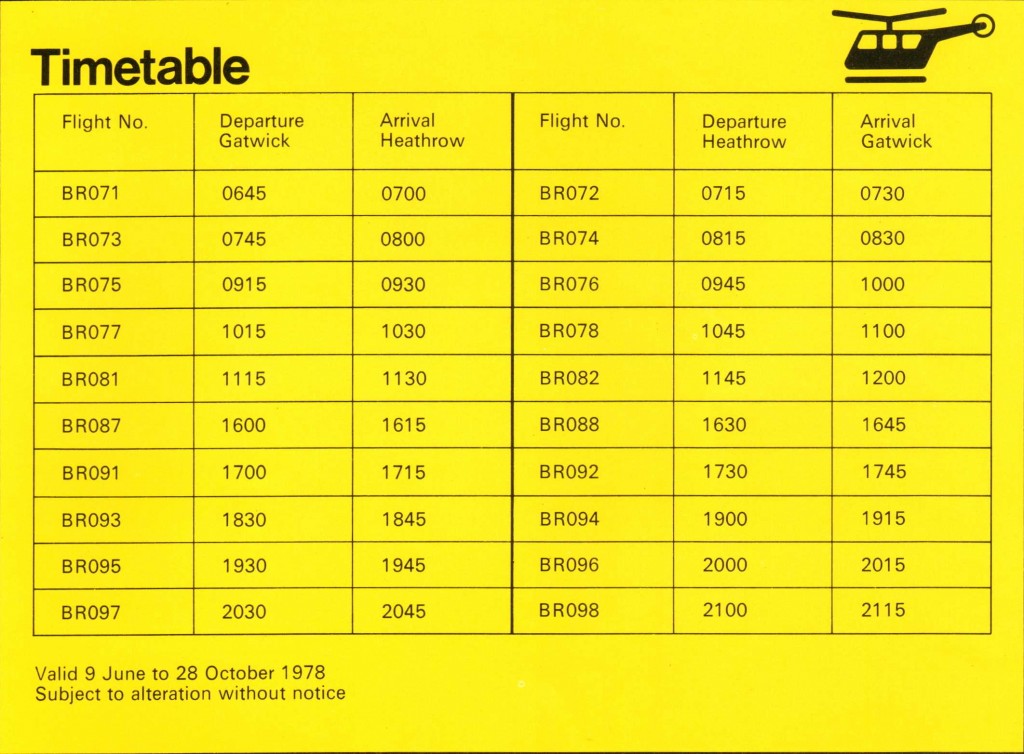

The front cover of the BCal pamphlet with Dawn Shuter, one of our Airlink Agents

Aviation breeds a special kind of individual. Enthusiasm, dedication and attention to detail are essential qualities if success is to be achieved and safety assured. This article is a revision of previous articles written by the author on this unique service. Apart from being a record of the technical and commercial expertise intrinsic to the service, it is a tribute to all of the men and women who contributed to the success and safety of the Gatwick/Heathrow Airlink. It contains some specialised detail in the hope that no matter the discipline, or former discipline of the reader, all will find sections of interest and relevance to their particular speciality. Anyone wishing to contribute to the article in the form of additions or corrections may do so using airlink@ashpole.org.uk.

Introduction and Background

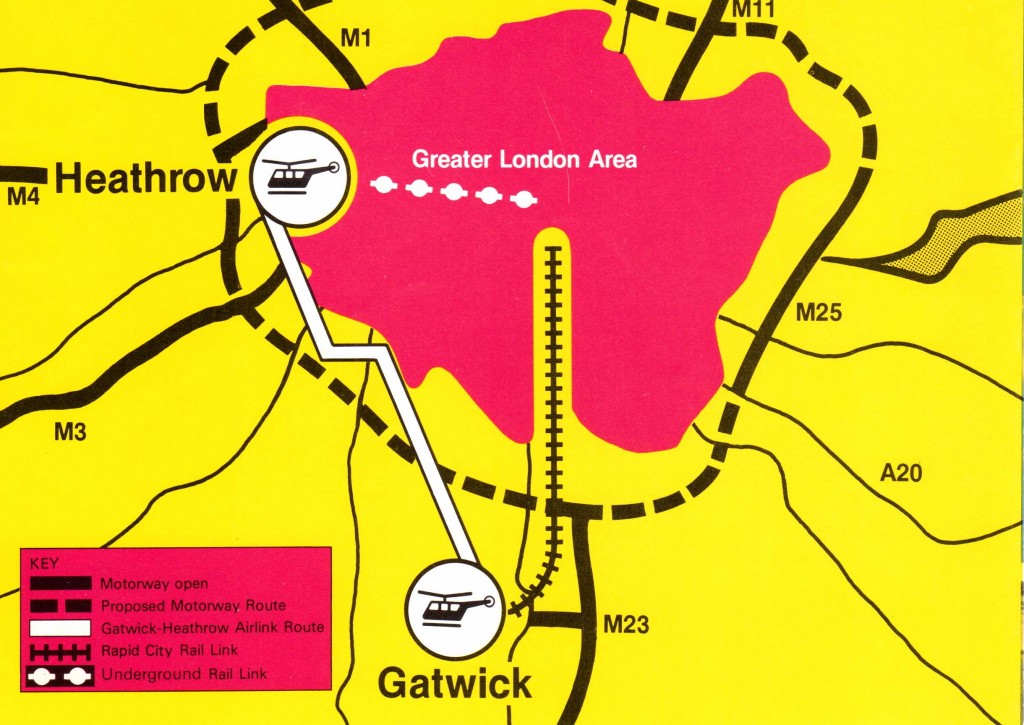

British Caledonian (BCal) was formed in 1971 as a result of the recommendations of the Edwards Committee. A key recommendation was that it should be based at London Gatwick thereby imposing an immediate penalty – the one runway Gatwick having the potential of only half the slots available for network and frequency development compared with the two runway Heathrow. Also, at that time, almost 50% of the operations at Gatwick were charters, leaving limited room for growth in peak scheduled services. The 1970’s was also a very different regulatory environment to that which would evolve later, with all routes requiring Route Licences from the newly formed Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) and overseas routes requiring Bilateral designation.

The usual consequence of these requirements was that only one carrier per nation was allowed to fly a route. Thus route development and service opportunities available to BCal at Gatwick were limited and those that did arise were the subject of fierce Licence hearings despite active Government and CAA licensing policy which favoured route development at London’s “second” airport. To fill the gap in Gatwick’s scheduled service network and provide vital connecting traffic opportunities to BCal, the “second force” airline needed to tap into the Heathrow network. BCal had for years run cars for its high yield traffic between the airports making use of Tristar limousines, but unlike the normal IATA Interline agreement, where the “delivering carrier pays”, BCal had borne the total cost of car transfers. Against this background of gaps in the BCal and Gatwick network and frequencies and, as a result of the US/UK Bermuda 2 agreement, with the prospect of new routes to the Southern USA opening in 1977 to Dallas, Houston and Atlanta, BCal looked to see how it could tap into the Heathrow network more effectively.

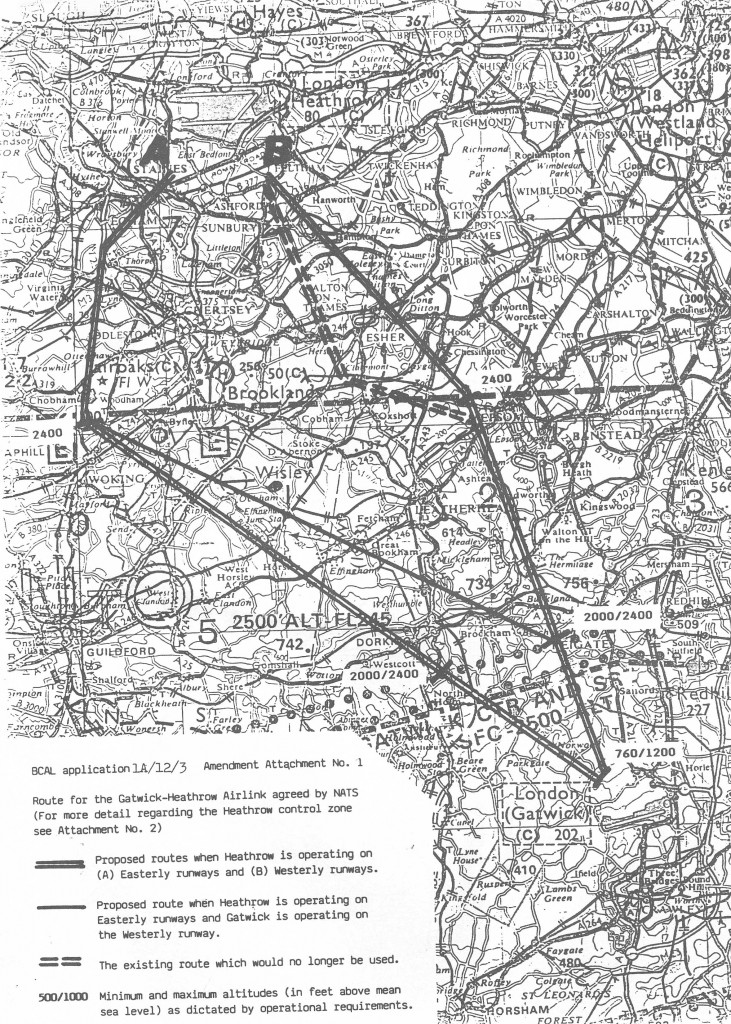

The BCal Planning Department, led by Alistair Pugh and John Prothero Thomas, was put on the case. They asked Laurie Price, then Manager Economic Strategy, to look at the options and liaise with BAA who were keen to promote their “Twin airport” system. There followed months of research, analysis and meetings. All options were considered. The then new DHC Dash 7 STOL (short take-off and landing) aircraft was demonstrated. Continuation of surface transport was not ruled out but it was finally concluded that a helicopter operation was most likely to succeed with least adverse impact on slot availability (even then) at Heathrow and Gatwick. A trip to New York followed to see the New York Airways inter airport helicopter operation. Many meetings were held with NATS* (National Air Traffic Services) and a lot of work ensued with potential new partners – BAA, British Airways Helicopters (BAH) and British Airways Executive Handling at Heathrow. (*Largely to explain the versatility of helicopter operational capability as an alternative to the lengthy aeroplane arrival procedure to Heathrow.)

Fundamental to the service was a requirement to gain a route licence from the CAA. BCal’s adroit Licence Application and Hearing team led by a formidable advocate, David Beety QC, BCal’s one time Secretary and Solicitor, was put on the case. David was assisted by Hugh O’Donovan who, like David, went on to assist in many BCal licence hearings at the CAA. It resulted in the first of five Airlink hearings and some of the most unusual to be faced by a CAA Panel. It was the first Air Service Licence Hearing where environmental issues were raised significantly and householders and local authorities were allowed to make representations; even the opportunistic local bus company objected! There was also an approach from a travel company in London – Air Link Travel accusing us of stealing their trade mark; so the operation became the Gatwick/Heathrow Airlink – although in reality it was always referred to as Airlink. The result of that hearing was the granting of a one year licence. Four further licence hearings were held and all were successful with the eventual grant of a licence that would run until the M23 / M25 link was open when the situation would be reviewed.

Rationale and Implementation

The Airlink scheduled helicopter service commenced operation in June 1978 as a fully commercial operation by British Caledonian Airways supported by the British Airports Authority. Both of these organisations had a vested interest in introducing a high speed connection between Gatwick and Heathrow airports (as explained above). Since neither had helicopter expertise, they turned to another company resident at Gatwick, British Airways Helicopters (BAH), who could provide the expert staff and equipment necessary for the CAA to issue an Air Operators Certificate (AOC) for the service. The original BAH Project Manager was Captain Don Huggett who was running the BAH Beccles operation at the time. Captain Stuart Birt, BAH Chief Pilot, also had a significant hand in preparing vital operational paperwork. With respect to persons involved it must be mentioned that Captain John (Jock) Cameron, Managing Director of BAH was as enthusiastic as any for the implementation and success of this service. He, alongside his contemporary, Alan Bristow, MD of Bristow Helicopters, were the two undisputed visionary grandfathers of British commercial helicopter operations.

So, the British Airports Authority was seeking to promote its second major airport, Gatwick, as a leading interline hub convenient to London and joined by an umbilical cord to Heathrow, the World’s premiere hub for interlining international passengers. British Caledonian Airways, the nation’s second largest major airline after British Airways, was keen to compete more effectively with airlines operating from a very highly dominant Heathrow hub and its rival BA. As mentioned earlier, in order to connect Gatwick with Heathrow, British Caledonian were hiring an ever increasing number of limousines to ferry passengers between the two airports. Surprisingly, for every passenger sent from Gatwick to Heathrow, only one returned. This indicated the high level of poaching being practised at Heathrow, a factor proving very costly to BCal as the second force airline.

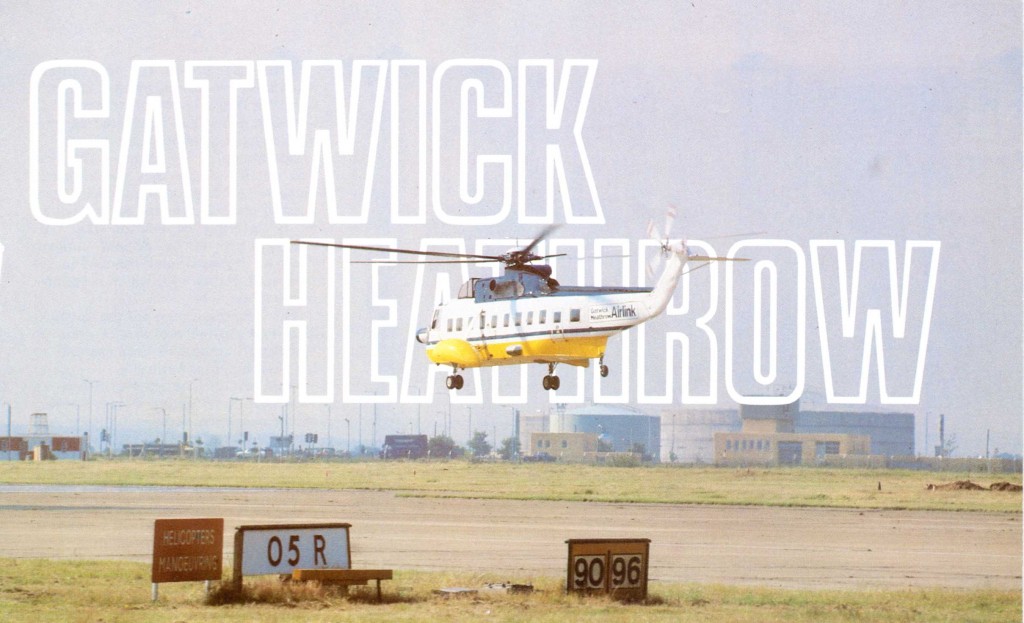

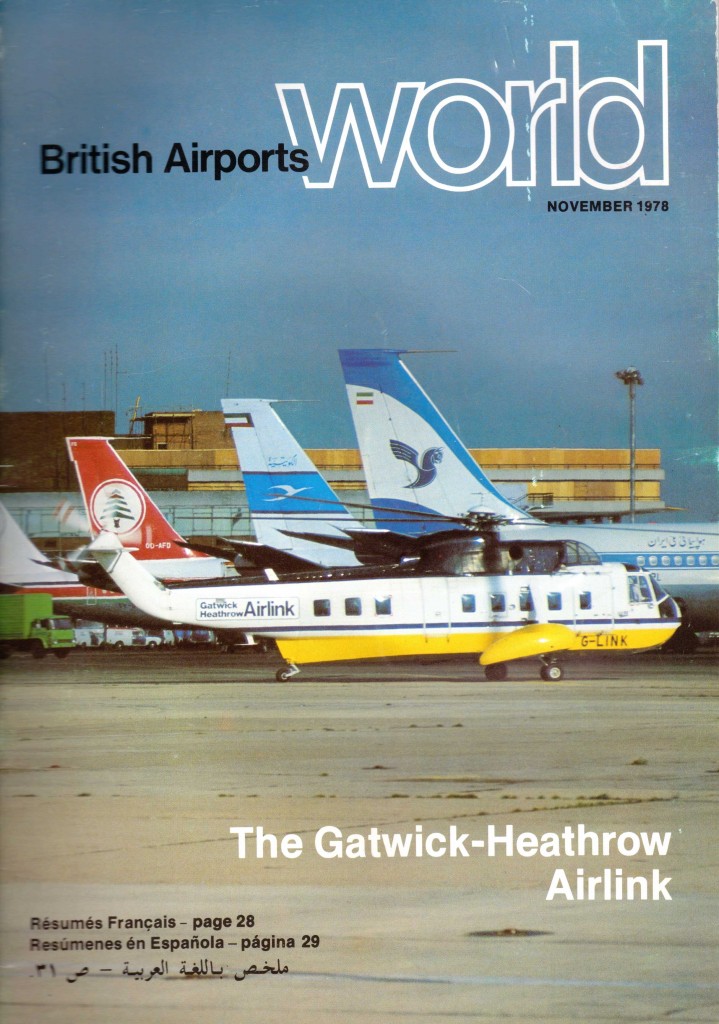

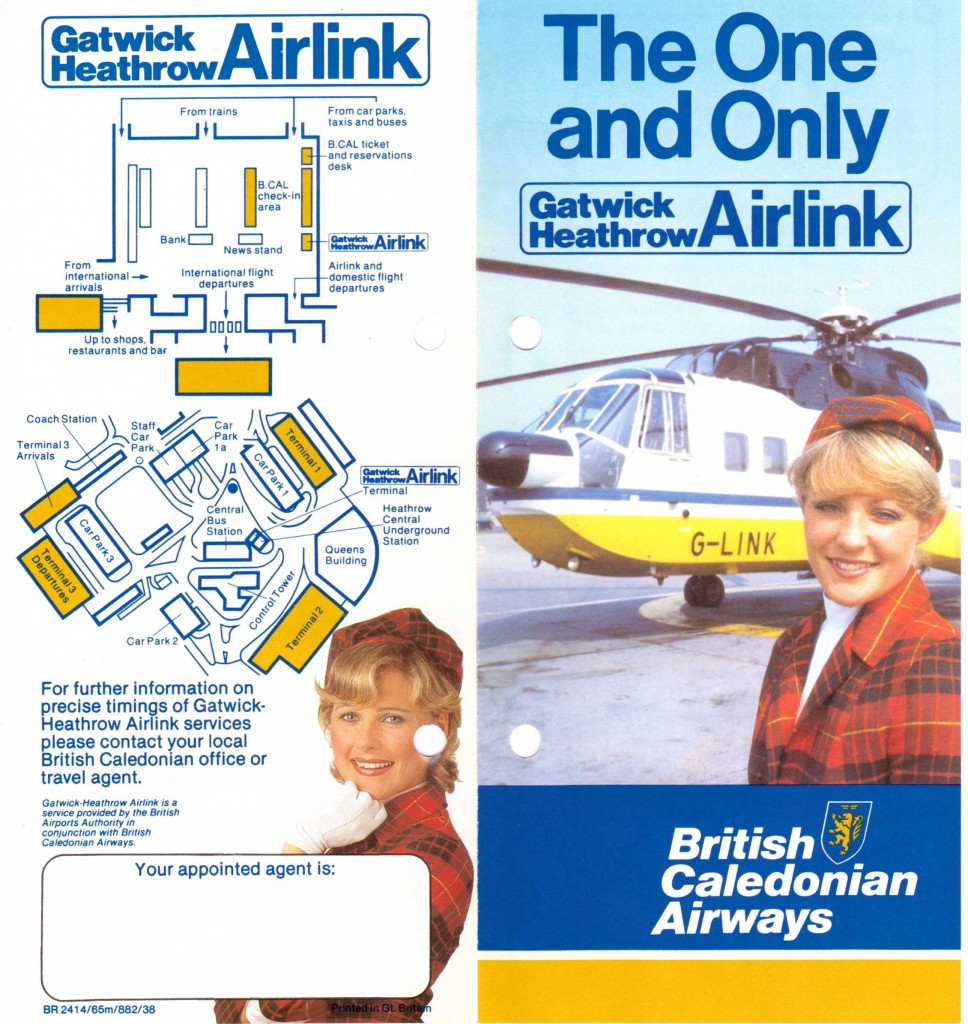

Following the decision that the helicopter provided the best solution, the British Airports Authority was persuaded to purchase one Sikorsky S61N helicopter, with appropriate UK registration G-LINK (proposed by BCAL), at a cost in 1978 of £2million. British Airways Helicopters provided pilots and engineers; British Caledonian Airways (BCal) provided the overall commercial management, took the financial risk and provided personnel to act both as cabin attendants and check-in staff, together with baggage handling staff at Gatwick. British Airways contracted to provide staff at Heathrow for passenger check-in and baggage handling. Operational management as Chief Pilot of the service was given to me as a senior captain in British Airways Helicopters with three years’ experience as the Manager of the BAH base in the Shetland Isles and three years on the Penzance/Isles of Scilly scheduled service – probably the longest running scheduled helicopter service in the World (1964-2012). Just before the commencement of the service, J.R.S. (Mick) Sidebotham, Operations Director of BCal, honoured me to be BCal’s Manager of this quadruple company enterprise.

Most of the international airlines operating through Gatwick and Heathrow became signatories to the special interline agreement with British Caledonian Airways, ironically these airlines now having to help pay for inter airport transfers which hitherto they had avoided. Under the terms of this agreement the airline which benefited from the long haul sector of a two or three leg itinerary would pay for the Airlink sector. If two airlines were involved in long haul sectors for a particular journey, with the Airlink sector as the middle leg, then each of the two airlines would share half the cost of the Airlink fare. Laurie Price, who was BCal’s Airlink Project Manager, having been involved in the conception of the Airlink service from the start, was responsible for negotiating interline agreements.

G-LINK arrives in Le Havre, France

The ship that brought G-LINK from the USA to Europe was the Atlantic Conveyor, the same ship that, four years later, was sunk off the Falklands by Argentinian Exocet missiles. There was a strike at Southampton Docks so the ship docked at Le Havre. Captain Tom Porteous and John James (who supplied these details) positioned to Le Havre with some engineers from Gatwick to collect the aircraft and perform flight tests. They flew G-LINK from Le Havre dock to Octeville to clear Customs and then to the Beehive at Gatwick on 4 May 1978. Below is probably the first photograph of G-LINK in Europe taken by a BAA photographer from an aeroplane hired by the BAA.

Captain Tom Porteous and John James flying G-LINK from Octeville in France to Gatwick with the engineers who assembled the helicopter after arrival in Le Havre.

Airlink commences operation

Prior to the inaugural flight, five days were spent on proving flights during which hundreds of airline and airport staff were flown between the two airports whilst we practiced passenger check-in, baggage handling, engineering considerations, rotors running refuelling and flight operations. All went smoothly.

A small group of Airlink staff prior to the inaugural. Laurie Price to the left looking towards the camera with Jonathan Oakes to his right. Paul Lacey and Dawn Shuter or Pauline in tartan. Mike Evans (far left), John Bamford (far right) and the author in BAH uniform. Probably Don Huggett hidden in group.

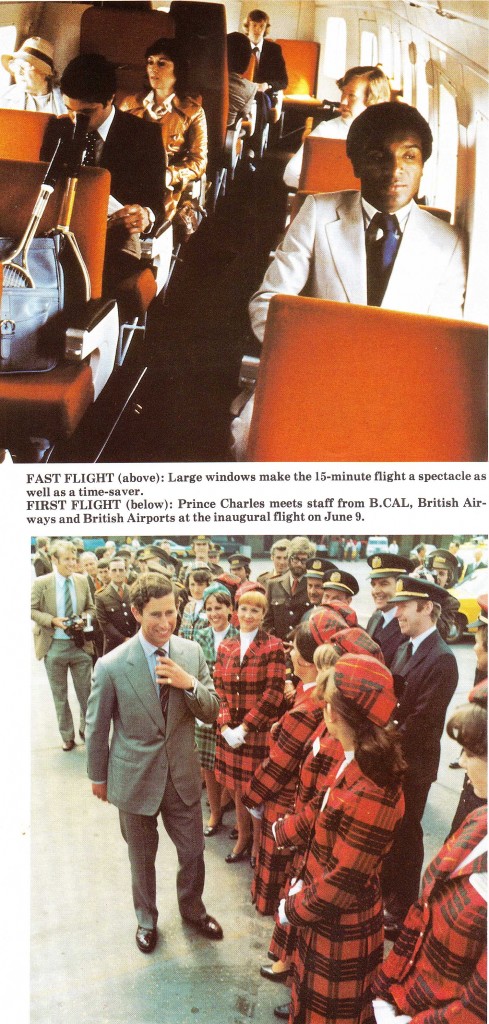

On 9th June, 1978. H R H Charles, Prince of Wales, travelled from Victoria to Gatwick on the inaugural Gatwick Express rail service. He then toured the extension to the South Terminal at Gatwick*. His third function of the day was to fly on the Gatwick/Heathrow Airlink inaugural. (*My thanks to David Hurst, Public Relations, British Airports Authority, Gatwick for this correction to the original text).

Line up of Airlink Agents and others awaiting the visit of Prince Charles prior to the inaugural flight

Prince Charles arrived at the side of the helicopter where a guard of honour of pilots, cabin staff and engineers were assembled. He then boarded the helicopter followed by several VIPs. In view of his special interest in aviation matters and the fact that he was a qualified helicopter pilot, he was invited to travel on the supernumerary crew seat in the cockpit between myself and Captain Don Huggett. The conversation included mention of the environmental issues and Prince Charles commented that he knew of such matters, Windsor Castle being in line with both runways at Heathrow!

It is usual, of course, for one to stand and bow when meeting royalty. However, in this occasion, in order to minimise delay, Don and I were strapped in and had completed the checklist ready to start no.1 engine. Prince Charles arrived at the small entrance to the cockpit and, whilst still standing, had to bow in order that we might shake hands and introduce ourselves!

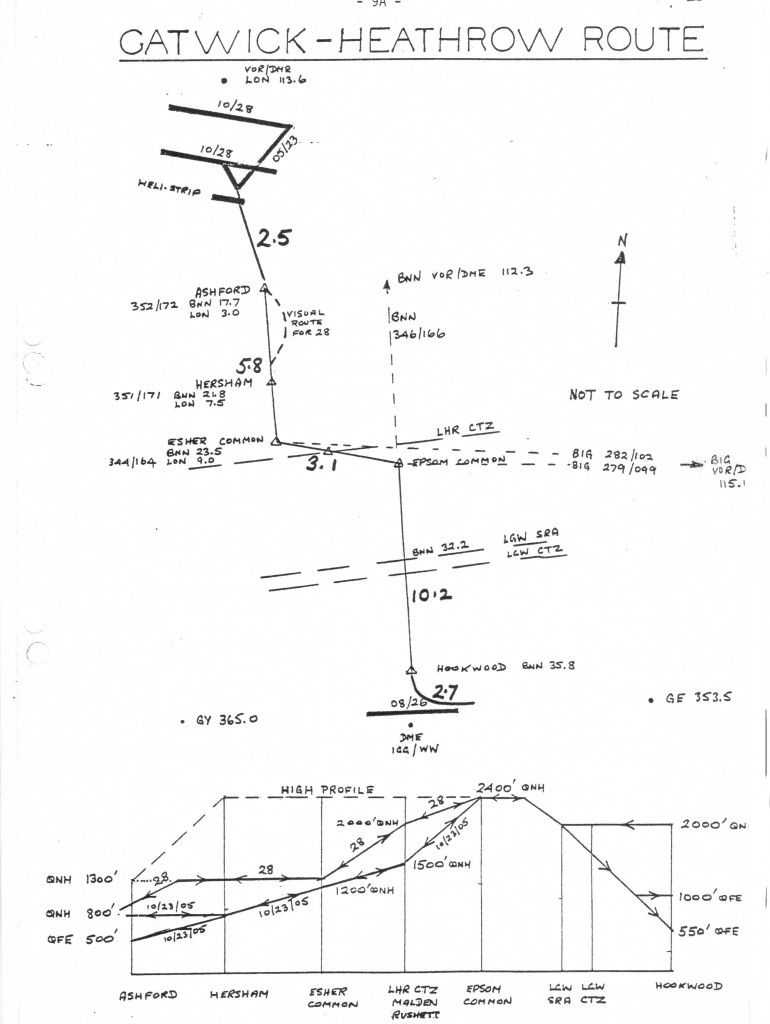

The Operation

In the early days of the operation air traffic control procedures were laborious (as had been anticipated during the initial protracted negotiations with NATS) the average sector time from stand to stand being in the region of 25 minutes. Almost 10 minutes of this was ground taxing and other ground delays. G-LINK started to go through brakes and tyres at an alarming rate, almost unprecedented in helicopter operations! During the inaugural flight, as we taxied for five minutes to the then take-off position, one of the VIPs on board, Freddie Laker, quipped “Oh we are going by road!” The practice of inviting air traffic controllers to fly on the supernumerary crew seat in the cockpit was encouraged. This quickly produced a dramatic reduction in sector times. These highly professional men soon learnt how versatile the machine was and realised that the helicopter was being held unnecessarily. With only 10 pilots dedicated to the Airlink operation, the controllers appreciated that they could completely rely upon their instructions being obeyed immediately and precisely. This fact, together with operational adjustments negotiated with the management of National Air Traffic Services, soon produced consistent sector times of just over 18 minutes block to block with an airborne time of just over 15 minutes i.e. all air traffic control holding on the ground together with all ground taxing amounted to an average of just three minutes in total per sector – a remarkable achievement by all concerned.

One cannot speak too highly of both the ATC controllers and their managers. Their understanding of our needs and their willingness to give us certain freedoms made many things possible. A particular example was the freedom we exercised in respect to vortex wake and jet blast. Generally speaking, the larger the aeroplane the greater the vortices emanating from each wing tip, vortices which can be highly disruptive to smaller aircraft which stray into them, even some miles or minutes later. Similarly, the larger the aircraft the greater the “blast” emanating from each engine at the commencement of the take-off roll. A landing “Heavy” aircraft, with flaps fully extended, creates considerable vortices. Although the air traffic operational instructions issued by NATS had taken vortices and jet blast into account, it was essential to the efficient operation of the helicopter that we could use our judgement in choosing a safe flight path during take-off and landing. Suffice it to say that the Airlink pilots became very skilful in ensuring a safe operation when operating close to the ground. Making the mistake of flying through the downward side of a vortex could be rather eye-watering!

Crucial to the success of the Airlink operation was the ability to operate with no impact on fixed wing operations. Each runway slot was precious and were the helicopter to significantly affect the capacity of either airport, Airlink would have ceased to be acceptable. Whilst it would have been relatively simple to operate as a VFR helicopter operation, the resulting regularity of service would have been inadequate for what was essentially a feeder service. An IFR capability was essential. (VFR – Visual Flight Rules – the pilot flies the aircraft using outside visual reference for control and navigation; IFR – Instrument Flight Rules – the pilot has the capability of flying the aircraft using cockpit instrumentation providing the pilot with spacial orientation and navigational information). The fact that British Airways Helicopters had pioneered the introduction of the commercial Instrument Rating for helicopters a few years earlier – the first of its kind in the World outside of the USSR – made this possible. In fact the author was awarded the third to be issued “certificate of competence to fly helicopters in IFR conditions” (the forerunner to the helicopter instrument rating). The holders of the first two were Captain Dave Eastwood, who had driven the programme with the CAA, and Captain Mike Perkis, former Manager of the BAH Penzance-Isles of Scilly helicopter scheduled service. State of the art navigation available to helicopters in 1978 was the Decca Navigator – a far cry from the versatile and extremely precise navigational equipment which would become available some years after the demise of Airlink with the advent of GPS.

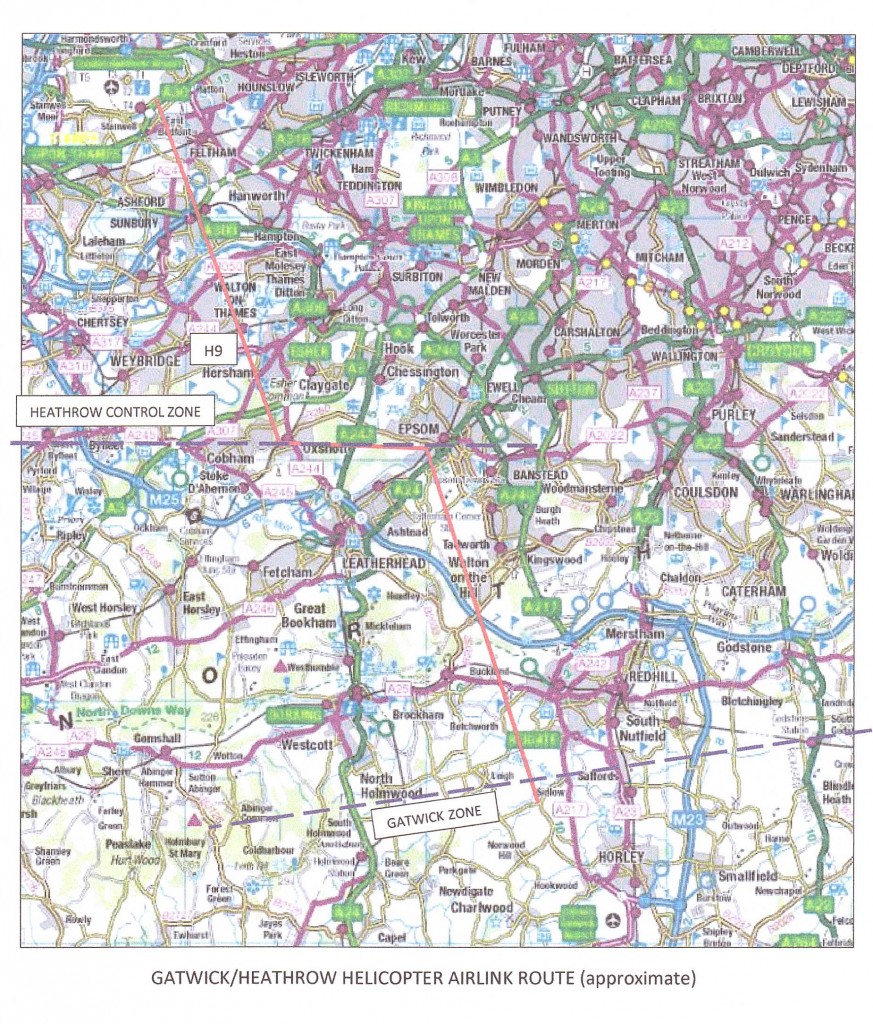

Decca provided the Airlink pilots with a moving map display in the cockpit giving approximately one inch to the mile representation of the route between the two airports. A very precise height and track profile was followed on every flight using this system. Essentially, whether flying visually or on instruments, the pilots would adjust heading to keep a pen, representing the aircraft’s position over the ground, on the line representing the official track. Thus the Airlink helicopter was able to fly through cloud and descend at the destination airport using a cloud break procedure. The final approach path of the helicopter was at 90 degrees to the orientation of the runways at Gatwick and Heathrow. Once visual with the ground, the helicopter would be given a landing clearance by air traffic control at a time and location which would not cause interference with aeroplane operations.

Initially at Heathrow a grass helicopter landing strip was laid out delineated with lighting. As the operation became more efficient from an ATC point of view, and we were cleared to land and depart from the southern end of the “V” formed by the two disused runways, the strip was abandoned. Eventually HAL asked if they could remove it.

The minimum descent altitude and minimum in-flight visibility permitted using this cloud break procedure were 550 feet QFE* at Gatwick and 500 feet QFE* at Heathrow and one kilometre respectively. In the event that visual contact with the ground was not achieved on the descent then the helicopter would perform a 180 degree turn and commence a climb. In the case of Gatwick the helicopter would then request radar vectoring for an ILS allowing a safe descent to 200 feet above the threshold of the runway in use by aeroplanes. (Instrument Landing System – the standard ICAO precision landing approach system installed at most airports around the World). On these few occasions when an ILS became necessary, the Airlink helicopter could have a small adverse impact on fixed wing operations. However, this impact was minimised by the pilots maintaining as high a speed as possible on the approach and clearing the runway centre line whilst still airborne when over the runway threshold. *QFE – above airfield level.

After a few months of operation, I began a project to achieve lower operating minima at Heathrow. As we were denied use of the ILS, I investigated a military instrument landing system manufactured by a firm in Crawley, next to Gatwick. The system called MADGE was a compact item which could be carried by two soldiers and “pegged” into a field. It was, in fact, a mobile microwave ILS system. I proposed that the MADGE equipment could be set up in proximity to the helicopter landing strip on the south side of Heathrow to give us minima similar to ILS. The senior manager of National Air Traffic Services with responsibility for Airlink matters was Ron Toseland, then head of ATC Heathrow but later to become Director General of NATS. Following my request, he organised a meeting of all departments in regulatory circles who would be concerned with the MADGE proposal. A meeting of over 20 individuals resulted! There was a lot of head scratching and shortly after Ron phoned me to propose an abandonment of the MADGE project in return for use of the regular ILS facility at Heathrow!

An unusual feature at Heathrow, was that the Airlink helicopter was permitted to carry out an ILS approach to one of the parallel runways whilst aeroplanes were landing simultaneously using the ILS on the other runway – a precursor of developments which would be needed later to cope with growth in aeroplane traffic at Heathrow. Using a combination of visual, Decca cloud break procedure and ILS, throughout the period of the Airlink operation from 1978 to 1986, loss of regularity due to weather factors was adequate for a feeder service, i.e. with few exceptions, aeroplanes (except those with BA’s Autoland) did not then have the capability of landing in lower weather minima than those of the helicopter, viz. 200 feet cloud ceiling and 300 metres. In fact, I recall one morning when flying into Heathrow with Captain Gerry Howie as co-pilot, we requested an ILS approach. We were given it with the comment that “no one else was trying!” We successfully landed on 10 Left with the weather almost exactly on our limits. If we thought that this was an experience, finding our way to the stand in the fog was something else!

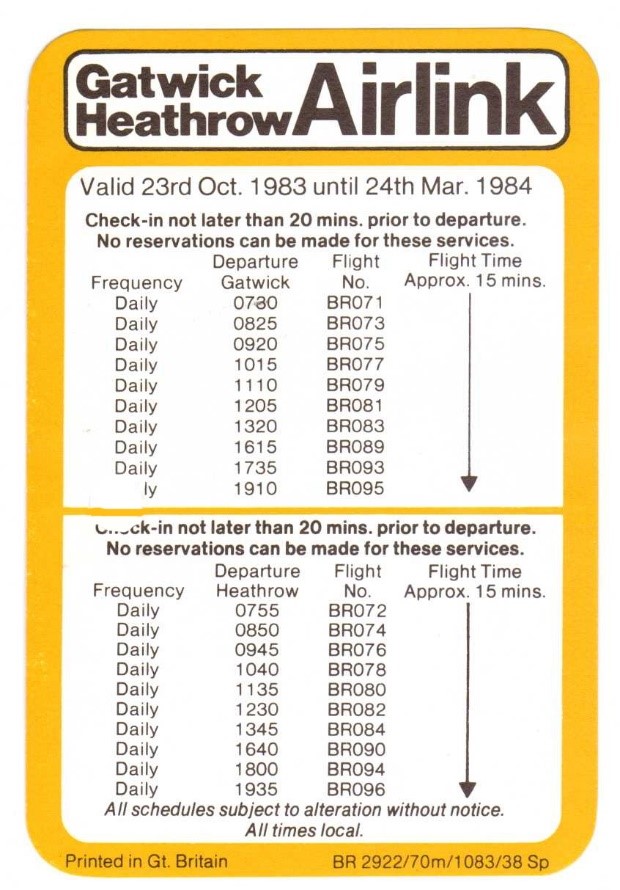

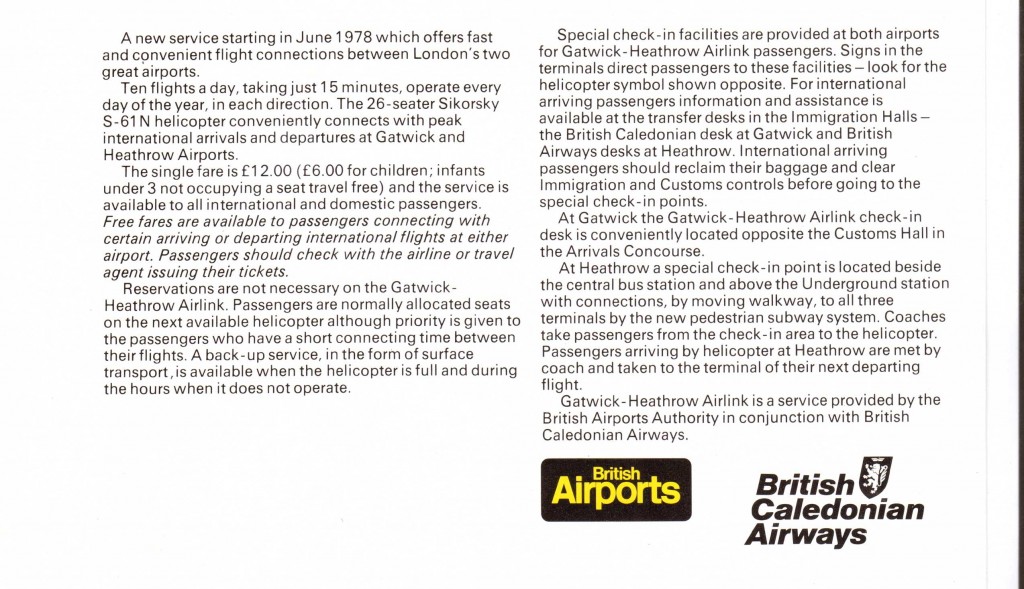

Six return flights of the total 10 daily return operations were scheduled almost consecutively commencing at 7:15 a.m. (The initial timetable commenced 30 minutes earlier but was revised in the light of experience). Such was the efficiency of the service that by keeping the rotors turning whilst passengers and baggage were loaded and offloaded and pressure refuelling following each arrival at Gatwick*, the single helicopter could be scheduled to leave Gatwick every 50 minutes. The remaining four return flights permitted by the CAA route licence were scheduled throughout the afternoon and evening with the last landing at Gatwick at 8:00 p.m. (*Refuelling each time permitted the maximum payload of passengers and baggage.)

An additional facility would have been introduced if it had not been for the untimely termination of the Airlink. Negotiations had been successfully concluded with HM Customs & Immigration, GAL (Gatwick Airport Ltd.) and HAL (Heathrow Airport Ltd.) for an “airside” operation, i.e. passengers would be treated as international throughout their Airlink transit and thus, if they were arriving from and departing to a foreign country, they would avoid the inconvenience of passing through customs and immigration controls at either airport. Permission was also included for passengers arriving from or departing to domestic flights to be carried on the helicopter. Thus only domestic to domestic passengers would have been ineligible for carriage.

The number of passengers travelling on the Airlink service rapidly increased. The morning flights experienced average load factors of over 80 per cent which, for a service without reservations, was extremely high and meant that many flights were full. The Gatwick/Heathrow Airlink became well known to the travel industry. The concept envisaged by the planners became reality in that these two major airports were now perceived by the travelling public as a mere 15 minutes apart – a very important marketing concept for British airlines and the BAA when promoting the multi-airport multi-terminal London airport system against competition such as the single airport single terminal Amsterdam Schiphol. Passengers found it extremely convenient and the popularity of Gatwick and Heathrow as interlining hubs was enhanced. The dominance that these two airports had achieved over the years in the World league of international passenger throughput was further strengthened against competitors such as Paris, Amsterdam and Frankfurt. It was calculated that this one helicopter was responsible for an additional interlining revenue benefit to British Caledonian Airways of some £6 million per annum and to British Airways £9million.

Passenger numbers on Airlink continued to increase to the point that the need for extra capacity became a concern. Dialogue commenced with Westland Helicopters, the British manufacturer of helicopters based at Yeovil in Somerset. They were offering the WG30 in a 14 seat configuration and were very keen that we should be a lead customer. The very rectangular box of a cabin gave good headroom but baggage capacity would have been a challenge. The economic case for operating such a machine was also proving elusive although we did hold hopes of a “deal”. Unfortunately, this project had to be abandoned with the arrival of the recession of the early 1980’s. The growth in airline passenger numbers declined and we continued with G-LINK alone. Westland did go on to manufacture and sell a number of WG30 aircraft and one was used on the Penzance/Isles of Scilly operation, Captain Terry Nelson being the manager, to supplement the S61NM.

Airlink was always a NON SMOKING service. There was insufficient time during the very short turnarounds for cleaners to come aboard the helicopter and smokers do tend to leave a mess of ash and cigarette packets. Following the demise of Airlink I was appointed Manager Domestic Operations for BCal and responsible for ground handling at the five airports, Manchester, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Prestwick and Jersey, served by BCal’s BAC-111 services. Using Airlink as an example, I suggested that these services should be made NON SMOKING. Apart from improving the environment for the non-smokers, the majority of our passengers, this innovation would also, I understand, have largely solved the problem that the engineers were having with the pressurised cabin vent valves (not the technical name). These had to be cleaned regularly to remove the gunge resulting from tobacco. Richard Havers, General Manager, and Arthur Jamieson, Marketing Manager, sucked their teeth but concluded that this was too revolutionary a step for that time. However, in view of the worldwide NO SMOKING policy now standard on all airlines, it goes to show that Airlink was a leading edge operation!

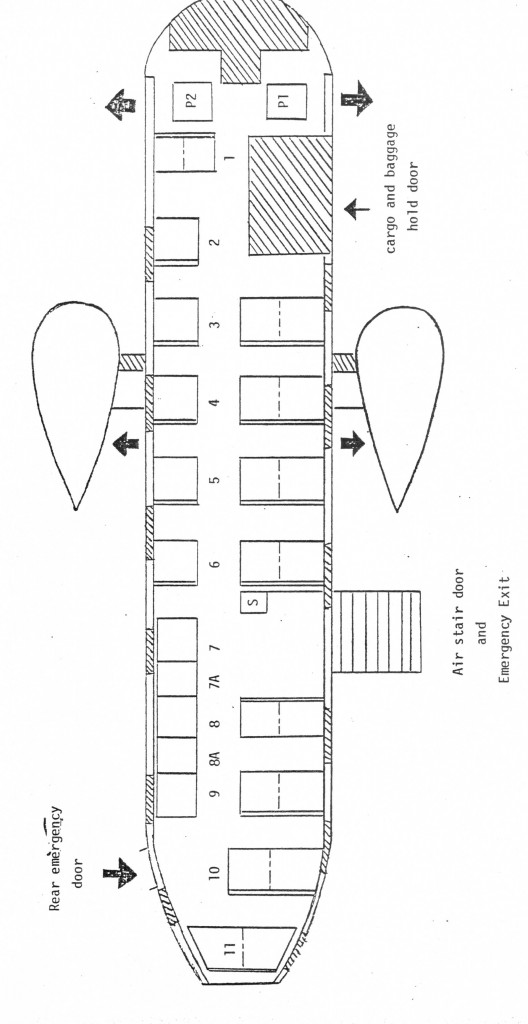

The amazing Sikorsky S61N

It would be remiss in an article on this subject not to mention the aircraft – the amazing Sikorsky S61N! This helicopter became the DC-3 of the North Sea and even today [2014] one can still see them flying in various roles including Search and Rescue. The military version still transports the President of the United States and HRH Prince William recently completed a tour of duty on the British military version, the Sea King. Sea Kings, flown by the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy, are still a vital part of UK military operations in Afghanistan and elsewhere. It is a superb aircraft, very resilient, with a very useful payload in a spacious small airliner style passenger cabin; 26 seats in the case of Airlink but 32 in the S61NM used on the BAH Penzance/Isles of Scilly service. Like others, I have flown the S61N between Shetland and Norway in forecast winds of 100 mph with reported wave heights of 50 feet, yet have felt every confidence in the machine to do its job. It was given a “light” icing clearance by the CAA – a rate of accretion of half an inch in 40 miles as detected on a thin metal rod in the air-stream just outside the captain’s window. This proved very useful on Airlink as well as all other operations. The “leading edge” ethos prevalent in British Airways Helicopters ensured we got the best from the machine in terms of performance and safety. Its faults are few but the poorly designed pilot’s seat is one. Made to a military specification, with the expectation of very low utilisation, perhaps 12 hours a month, it became an instrument of torture when used on a commercial operation with many more hours being flown each month by individual pilots, perhaps 80. Back problems were prevalent as a certain chiropractor at Penzance, who had treated nearly all the pilots based there over the years, testified. I, and others, were regular sufferers, but when I ceased to fly the S61N backache became history.

Our passengers

The itinerary of a typical Airlink passenger might be from Lagos in Nigeria to Washington in the USA. On arrival at Gatwick from Lagos our passenger, typically male with hold baggage of 44 kilograms, would clear customs and immigration and report to the Airlink check-in desk. Here he would show his ticket which would probably include the Airlink sector. His hold baggage would be accepted at the Airlink desk and he would wait in the Airlink lounge for the next helicopter to Heathrow. Upon arrival at Heathrow he would again be a reunited with his hold baggage and proceed to check-in for the British Airways flight to Washington. Thus from the time he checked in with British Caledonian Airways at Lagos to the time he arrived in Washington our passenger would know that he was “contained” within the airline system – a very important “comfort and security” consideration for international interline passengers. The service began with G-LINK configured with 28 passenger seats. It soon became apparent that our typical passenger brought with him or her a considerable amount of baggage. The baggage handlers strived magnificently to squeeze it into the forward hold, which included a vertical extension up to the cabin ceiling from the original hold in the hull, but this delayed departure and was sometimes impossible. It was decided to sacrifice two passenger seats in favour of a larger hold. Operating with 26 seats completely solved the problem.

Airlink’s 200,000th passenger – Mr P de Agurusighe – itinerary – Columbo, Sri Lanka to Gatwick to Heathrow to California; J. R (Mick) Sidebotham, Operations Director BCal with Airlink Agent Jean Longland

The BAH base at Gatwick, the Beehive and the hangar, were only a few hundred yards from Stand 1, used exclusively by G-LINK and immediately adjacent to the runway and the Airlink offices and crew rooms. First thing each morning and after the last flight in the evening, the helicopter would be positioned between the base and the stand. One morning, with a very low cloud base and visibility and with no aeroplane traffic, two of our intrepid pilots, who shall remain anonymous, took off and climbed a little too high. Losing sight of the surface they had no alternative but to continue climbing and request an ILS! So their positioning flight of 3 minutes took nearer 15 – the record for the longest positioning flight!

Airlink’s First Birthday Left to right: Bob Manning, George Chatwin, ?; Author; Chris Elvery, Alan Stewart, Shell refueller?

The roster provided for one crew of two pilots to operate the first five return flights and a second crew to operate the remaining five. Given low cloud and poor visibility, it would have been possible to carry out 10 ILS approaches during one shift – an exceptional task piloting an aircraft with no autopilot and just an AFCS (a stability augmentation system). No-one, to my knowledge, ever took the prize.  We had the occasional addition to the Gatwick/Heathrow/Gatwick run, Father Christmas transport being one such. Another interesting operation for which we were fully prepared but were never called upon to perform was requested by the London Flood Emergency Team. It had been realised that whilst work was still in progress on the Thames Barrier, many of the team were based south of the Thames and in the event of serious flooding they would not be able to travel to the London Flood HQ on the north side. An Airlink operations order was carried in the cockpit which detailed the procedure to be followed in the event of a callout, namely to fly to Kenley aerodrome to pick up the team then fly them to the White City Stadium. Another interesting diversion was the replacement of two air conditioning units on the roof of the South Terminal at Gatwick (described next to the photo of the operation). Charlwood, a small village just to the north-west of Gatwick airport held a festival in 1980 to celebrate its 900th anniversary. A video of the visit to the festival by G-LINK can be seen on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bUGUf5JqHuw .

We had the occasional addition to the Gatwick/Heathrow/Gatwick run, Father Christmas transport being one such. Another interesting operation for which we were fully prepared but were never called upon to perform was requested by the London Flood Emergency Team. It had been realised that whilst work was still in progress on the Thames Barrier, many of the team were based south of the Thames and in the event of serious flooding they would not be able to travel to the London Flood HQ on the north side. An Airlink operations order was carried in the cockpit which detailed the procedure to be followed in the event of a callout, namely to fly to Kenley aerodrome to pick up the team then fly them to the White City Stadium. Another interesting diversion was the replacement of two air conditioning units on the roof of the South Terminal at Gatwick (described next to the photo of the operation). Charlwood, a small village just to the north-west of Gatwick airport held a festival in 1980 to celebrate its 900th anniversary. A video of the visit to the festival by G-LINK can be seen on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bUGUf5JqHuw .

Celebrity Passengers

Apart from HRH, The Prince of Wales on the inaugural flight, we did occasionally carry a celebrity. I looked back into the passenger cabin on one flight and saw Ian Paisley, Baron Bannside, the Northern Irish loyalist politician and who served as First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2007 to 2008. Below is a photograph of Harry Secombe, one of Britain’s most loved stars of show business having been flown by Captain Robin Morgan, F/O Dave Prince and Airlink Agent Fiona George. Harry was particularly famous for his singing voice, the Goon Show and the film “Oliver”. Harry was travelling that day with his film crew whilst making a TV programme called “Highway”.

A screaming experience

Very occasionally as a pilot one has cause to believe that the “Grim Reaper” has come to claim another victim. One flight I will never forget was one from Heathrow with a full load. We took off and headed south towards Gatwick. Less than two minutes after take-off an excruciating and very loud noise almost deafened us. It was the sound of metal scraping on metal and appeared to emanate from somewhere above and behind the cockpit. Immediately thought sprang to an engine or gearbox malfunction but a quick check of instrumentation indicated all was normal. The noise was truly terrifying! Disaster appeared imminent! I quickly turned G-LINK through 180° and headed back to Heathrow. Whilst I handled the aircraft and radio, John Lutkin as co-pilot, very quickly ran through the landing checks. At some point during the few seconds before touchdown the noise stopped. We landed and taxied back onto stand and shut down. All appeared normal and we had absolutely no idea what had caused the awful noise. There was no alternative but to send the passengers by road to Gatwick and wait for engineers to arrive to investigate. They discovered that the heater fan bearing had failed allowing the fan to scrape against the inside of its assembly. If there had been more time from the onset of the problem to achieving a safe touchdown then John might have picked up on the fact that the noise ceased when he switched off the heater. But given the very urgent situation presented to us it can be no wonder that the association was missed. All things considered I put this experience, particularly during the period of the screaming noise, in my very thin file marked moments of “stark terror”!

Something different

CAA Licence Hearings

The weakness of Airlink was not in its conception, profitability or operation but in the politics of environmental protest. The first year of operation was proposed on a trial basis and was subject to a CAA route licence hearing. Normally only airlines are represented at such hearings but, in view of the considerable environmental interest which arose because of the relatively low altitudes flown by the helicopter, the CAA decided to permit the so-called environmental lobby to be present and make their representations. This fateful decision gave a number of frustrated people and organisations the platform that they needed to promote their views. Using this new forum to advantage they wasted no time in introducing all kinds of anti-aviation arguments many of which had little relevance to the helicopter service. The CAA panel were charged by statute to consider environmental matters but to make their decision primarily upon the benefit to British commercial aviation. Having considered all the evidence, the CAA decided in favour of granting the application. The decision was referred to the Secretary of State, in accordance with procedure, and the route licence was granted for a period of 18 months. Further Airlink hearings were held by the CAA. On every application the CAA panel were convinced of the considerable interline benefit to British aviation. The Secretary of State endorsed their decision on every occasion except the penultimate when he directed that Airlink would cease 4 months after the completion of the south-west segment of the M25 Motorway. One final hearing took place to contest this decision but with the same result.

Hearing anecdotes

During one exchange at the first hearing in London between Laurie Price, as the main economic witness for BCal, and Mr Seward QC representing Surrey County Council, Mr Seward started a long expose saying: “Now tell me if a passenger turns up at 11 minutes past 8 for an 8:10 departure, he has to wait until 09:10, and if he turns up at 09:11 for a 09:10 departure he has to wait until 10:10 …” and so he went on and on. The reply from the BCAL witness was “well Mr Seward, you do seem to have chosen a most unfortunate passenger!”, which brought the house down, arousing much mirth, unusual for a CAA licence hearing and rather making the point. The CAA Panel were most appreciative having not taken kindly to the excessive use of legal bombast as CAA hearings were Quasi-Judicial and rather less formal than Courts of Law but nonetheless still very effective and challenging.

Another incident of relief to the proceedings at another hearing was occasioned by a Member of Parliament who was present to give voice to his objections to the service. Red-faced and rocking backwards and forwards on his chair whilst speaking he boomed “no one has needs so time critical that the saving of the few minutes afforded by the helicopter can be justified”. He completed giving his evidence and then said “well, must dash now, the House is sitting”. Followed by roars of laughter our QC, David Beety, remarked “well isn’t that interesting Mr X, it seems that only members of Parliament have time-critical needs!”

David Beety confided in us concerning a technique which lawyers call “a fishing trip”. He employed it when dealing with a man representing an environmental group along the route – the Meath Green Preservation Society. The man stated that the helicopter service could not be justified as road traffic between the two airports did not cause the delays claimed by the operators. David then turned the conversation to other matters then asked about road congestion in the area represented by this individual. “Awful” said the man. “And how about traffic between your house and Heathrow?” asked David. “Absolutely terrible – it takes hours to get anywhere!” was the quick reply. Game, set and match!

Another interesting contribution to one of the hearings was made by Cunli Fatona, then a BCal Sales Manager from Nigeria. During cross-examination, possibly by Mr Seward, he said that many Nigerian passengers favoured the safety and security of an air transfer rather than a bus. Mr Seward was most indignant and said “but this is Britain” to which the reply was “well what about the IRA!” .Point made and won! It was just after a military coach had been blown up by the IRA on the M62. This episode was a powerful illustration that assumptions by British commentators on safety and security in England may well be irrelevant to airline passengers who are residents of other countries where travel by road can be hazardous. (I remember a visit to Lagos in Nigeria on airline business when, on the journey from the airport to the hotel, my taxi was stopped by the police in a dimly lit side street . I was asked to open my suitcase and it became clear that the police sergeant was keen that I should give him a small electronic item. I was eventually permitted to go on my way unmolested!)

The Environmental Lobby

Within a few weeks following the inaugural flight, I was invited by Barney Barclay, Chief of Airside Safety& Operations of BAA Gatwick to attend a meeting of half a dozen of “his friends” living under or near the Airlink route. This meeting was reported in the local Press and I was met with a room packed with some 40 hostile residents! One of the main conclusions of this meeting was an undertaking to fly the helicopter within one quarter of a mile of the nominal track between the two airports and an assurance that the helicopter would be flown at the maximum altitude permitted by air traffic control. This undertaking was adhered to throughout the eight years of operation of Airlink making this service, arguably, the most precisely flown commercial operation in the history of aviation prior to the advent of GPS.![]()

As the years rolled by, environmental opposition became more organised. In spite of the tremendous efforts made by us to minimise environmental intrusion to residents, the claims became more exaggerated and, sometimes quite ridiculous. Letters of complaint were received charging the operators with flying in formation (only one helicopter was ever employed); of flying late at night (whilst the helicopter was on maintenance in the hangar); of flying far off track (in spite of being under radar surveillance at all times by air traffic control); that passengers could be using binoculars to spy on residents using their swimming pools! One man in particular to the south-west of Reigate was convinced that his daughter was the subject of aerial spying. Since our route took the helicopter almost directly over his property, G-LINK would have needed a glass bottom for anyone to see this young lady. Also, from a height of nearly half a mile, one wonders what this man thought we would be capable of seeing! This “nice” man sent me a gloating letter following the Government decision to terminate the service!

A lady living near Heathrow even sent me her underslip which, she claimed, had been stained by oil dripping from the helicopter. I had it analysed to prove we were innocent. One day I received a call from the office of the managing director of BCal concerning a complaint from the Oxshott area. Airlink was charged with flying at a low level over a particularly wealthy resident who was very well connected. He knew it was the Airlink helicopter because he recognised the shape. A quick telephone call to air traffic control at Heathrow established that the offending helicopter was a Royal Navy Sea King helicopter which would have passed overhead Oxshott in accordance with the rules governing flight along the established London Control Zone helicopter route, a height lower than that that permitted for the Airlink operation.

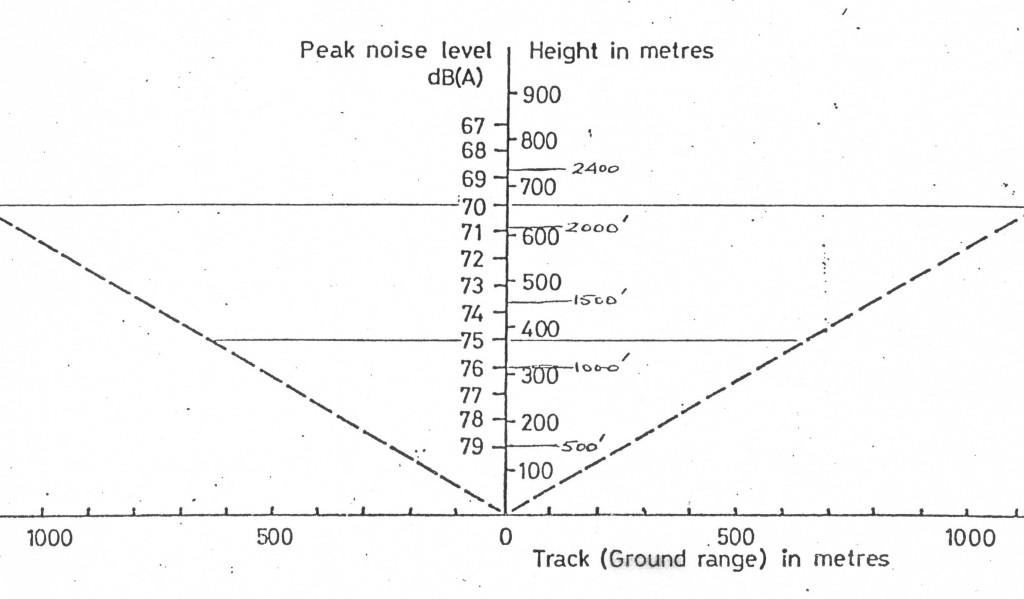

The facts were that the helicopter was flown extremely precisely and safely and both the visual and aural intrusion to those on the ground was minimal. The noise signature of the S61N helicopter was modest in spite of its size and was scientifically measured to be equivalent to that of a car travelling at 30 mph. passing an observer 32 feet away. In the suburban locations overflown by Airlink, road traffic and aeroplane noise was far in excess of any disturbance caused by the helicopter. Within the Heathrow air traffic control zone Airlink accounted for only one in five helicopter movements.

On one occasion the CAA Panel stood with complainers awaiting the overflight of this noisy beast! As the helicopter approached a lorry drove by completely drowning out the sound of the helicopter! On another occasion I was invited to the home of a couple resident near Gatwick to witness the “din”. As we waited I could hear the sound of shotguns nearby. “Oh, that’s our neighbour’s skeet shoot – we have one ourselves!” So it would appear that hours of volleys by shotguns were preferred to a few helicopter flights! – These were nice people but, I thought, somewhat hypocritical?

At the beginning of the service, GAL had appointed its own Manager Airlink whose role was to handle environmental complaints. David Shepherd performed this role in an exemplary fashion, liaising with me to establish the facts as regards individual flights subject to criticism. Once the service had been running for several months and the complaint situation was well in hand, David’s role was disestablished and he was given other assignments within GAL.

Dealing with environmental complaints was an eye-opener. The route had a 900 turn around “The Wells” – a large council housing estate near Epsom. I think we had perhaps two complaints from this estate during the eight years of operation. But other areas, in which there was more expensive housing, generated the majority of complaints. Some of this could be put down to a lower altitude being flown than near Epsom but many complaints had no relevance to this factor. We were told that certain very expensive properties overflown were owned by persons very influential in the opposition to the service. We were “threatened” by certain individuals that “they had friends in high places”….. The whole exercise was an interesting reflection on democracy in “our green and pleasant land”. One gentleman, who claimed influence at high level, spoke to us some months before the final decision to stop the service was made by the Secretary of State. He told us, in no uncertain terms, that he was completely confident that the Government would terminate the service!

UNLIKE ALL OTHER HELICOPTER TRAFFIC USING HELICOPTER ROUTE 9 SOUTH OF HEATHROW, AIRLINK FLIGHTS , FOLLOWING REQUEST BY THE PILOTS, AND SOMETIMES WITHOUT THEM EVEN ASKING, WERE GIVEN “HIGH PROFILE” CLEARANCES BY ATC. THIS ALLOWED G-LINK TO REMAIN AT 2,400 FEET A.M.S.L. UNTIL VERY CLOSE TO HEATHROW ON NORTHBOUND FLIGHTS AND CLIMB TO 2.400 FEET A.M.S.L. IMMEDIATELY AFTER DEPARTURE FROM HEATHROW. ALL THIS WAS DONE IN ORDER TO FLY AS GOOD NEIGHBOURS BY REDUCING THE NOISE AND VISUAL FOOTPRINT TO THOSE LIVING UNDER THE ROUTE.

UNLIKE ALL OTHER HELICOPTER TRAFFIC USING HELICOPTER ROUTE 9 SOUTH OF HEATHROW, AIRLINK FLIGHTS , FOLLOWING REQUEST BY THE PILOTS, AND SOMETIMES WITHOUT THEM EVEN ASKING, WERE GIVEN “HIGH PROFILE” CLEARANCES BY ATC. THIS ALLOWED G-LINK TO REMAIN AT 2,400 FEET A.M.S.L. UNTIL VERY CLOSE TO HEATHROW ON NORTHBOUND FLIGHTS AND CLIMB TO 2.400 FEET A.M.S.L. IMMEDIATELY AFTER DEPARTURE FROM HEATHROW. ALL THIS WAS DONE IN ORDER TO FLY AS GOOD NEIGHBOURS BY REDUCING THE NOISE AND VISUAL FOOTPRINT TO THOSE LIVING UNDER THE ROUTE.

In our efforts to fly in the most neighbourly manner possible I progressed a suggestion made during a discussion with a Mrs Attlee who was Chairman of FHANG (Federation of Heathrow Anti-Noise Groups). We discussed the advisability of splitting the intrusion of the helicopter by flying a two route system. The dilemma of doing so required the Wisdom of Solomon. Remaining with just one route meant dealing with existing objectors: a twin route system, although environmentally beneficial, would introduce a whole new set of complainants. We decided in favour of the “honest” solution – the one which would reduce environmental impact to the minimum for any individual overflown.

Captain Graeme Thompson of BCalH and I met with NATS and after considerable discussion, even argument, the managers present agreed the two routes. At the final licence hearing, we proposed this new twin route system which would give air traffic control the flexibility to permit the helicopter to remain at higher altitude for longer albeit that the maximum of 2,400 feet amsl could not be exceeded. This would have halved the intrusion for most of those living under the route.

One feature of the twin route system was the need to cater for the few hours each year when Heathrow had arriving/departing aircraft pointing in the opposite direction those at Gatwick. The route for these dozen or so flights per year would have overflown the Royal Horticultural Society gardens at Wisley. I received objections from as far afield as New Zealand! Yet one tractor in the gardens would have drowned out the noise of the helicopter. However, I have discovered by experience that there is no point trying to reason with unreasonable people.

There is an interesting conundrum when selecting a route. The obvious may be to draw a line over open countryside and avoid built-up areas. The paradox is that fewer people would be overflown but in areas with very low ambient noise levels an aircraft is more intrusive. There is also an argument that a relatively quiet aircraft flying over a busy urban area would not be heard above the day-to-day ambient noise of road traffic, etc. It was an interesting fact that I received a minimal number of complaints from a street to the south of Heathrow, a street directly under Helicopter Route 9 and flown at heights as low as 500 feet by all helicopter traffic including Airlink. On one occasion I was invited by Heathrow Airport Ltd to attend a meeting of residents who lived along and nearby this street. Expecting a certain level of hostility, I was surprised to learn that those present believed they were attending a meeting to protest about aeroplane noise at Heathrow. They seemed annoyed that the meeting had been called to discuss the Airlink helicopter and had little concern over it. At one point one gentleman queried the safety of helicopters on the premise that (he claimed) the Technical Secretary of the British Airline Pilots Association (BALPA) had said that helicopters were unsafe. I refuted his argument assuring those present that they were safe and as a family man I would not spend hundreds of hours each year as a pilot if I had any doubts. He then asked whether I felt I was more of an expert on the subject than the BALPA official. I replied that I was confident that I was. Immediately, others in the audience shouted “of course he is!” One can find friends in unlikely places.

Incidentally, whilst on the subject of noise, I have always found it strange that in my early days training to be a pilot in the RAF, it was a golden rule never to fly near hospitals. Yet anyone who has had the misfortune to stay in a hospital knows full well that the environment on the ward is often extremely noisy, even at night, due to the apparent unawareness of the staff of the noise they are creating, including loud chatter!

The staff of Airlink

No article on Airlink would be complete without mention of all the staff who made it possible. This includes not only the pilots but, of equal importance, the engineers and cabin staff/check-in staff dedicated to the service and the baggage handlers drawn from the general pool at both ends of the route. In addition, the British Airways team at Heathrow, also dedicated to the operation under their manager, Geoff Fordham, were exemplary in their handling of passengers and delivery to and from the helicopter. By “dedicated” I mean not only were they assigned exclusively to Airlink but by their approach to the job and their actions on the job they showed a complete dedication to giving of their best in the interests of the service. Although employed by four different companies, they worked as if one – the Gatwick/Heathrow Helicopter Airlink. I look back with many fond and appreciative memories of them all.

In fact there was another company which became involved in Airlink – British Caledonian Helicopters. After several years of operation with the pilots and engineers of BAH, new senior management in BAH decided to raise the contract price for their services. A double hike took place whereupon BCal felt it necessary to look elsewhere. There was now a choice alternative in the form of the BCal Group’s recently acquired helicopter subsidiary – BCal Helicopters – a takeover of Ferranti Helicopters. Bob Macleod, Managing Director of BCalH, was hungry for the business and so the staff of BAH were replaced by those of BCalH. The service continued with the same dedication as before. I had taken severance from BAH in May 1983 and joined BCal some time prior to this change of staff. I continued to manage Airlink as well as other operations within BCal. BAH appointed John Lutkin to take my place as Chief Pilot. He was replaced by Ken Brett. When BCalH took over the operation, Graeme Thomson became Chief Pilot. Another important change to the management of Airlink was the retirement of Mick Sidebotham. I now reported to the new BCal Operations Director, John Prothero-Thomas, as well as frequent contacts with Bob Macleod, based in Aberdeen.

The engineers performed magnificently in maintaining G-LINK. One must bear in mind that there was no back up aircraft. If G-LINK went unserviceable then it had to be fixed with the minimum of delay. The engineers were led by the Airlink Station Engineer, Harvey Pole for most of the life of the service (1978 to 1984) and Derek Hapgood during the latter days when BCal Helicopters took over from British Airways Helicopters (1984 to 1986). In fact G-LINK had the highest daily utilisation of any S61N of the many on the UK register.

Stephanie O’Connor, one of the Airlink Agents, with Nigel Maddock of the British Airways Handling Unit at Heathrow (photo courtesy of Stephanie Hawkey)

The service began with two male staff and eight female Airlink Agents. This was initially organised by Bob Manning but later placed under the supervision of Sally Caine, then Suzanne Taylor and finally Frances Thompson. The staff were given the title of “Airlink Agents” as they performed duties as flight attendants and check-in staff at Gatwick. The female cabin staff dressed in the famous and very attractive BCal uniform. The kilted skirts, with the Cameron tartan in respect of Jock Cameron (MD of BAH), were weighed down at the hem for reason of modesty. Normally the weights would be adequate in the downdraft from the main rotor at minimum pitch during rotors running turnarounds. However, I have heard tell of incidents when some cheeky pilot has been known to raise the collective lever….! Last but not least was Betty Wells, my secretary, who took over from Frances Grant. Betty was, and remains still, a central figure in maintaining contact with many of the former staff. She organised a number of Airlink get-togethers. The role of Betty and her predecessor and successor, Sandra Groves, included keeping Airlink statistics and many other vital clerical functions to enable the service to work effectively.

The Demise of Airlink

The demise of this tremendously successful service was totally political. Realising that the environmental lobby had many friends in government circles, the operators commenced lobbying members of Parliament. Some 70 members offered their support. Captain Peter Hounsome, one of the Airlink pilots, organised a petition to gain support for the service. His efforts were rewarded with over 7,000 signatures, far more than the total lobby of the opposition. He and another pilot visited Nicholas Soames, MP for Crawley. He said he had been under the impression that no-one was pro the helicopter service. To his credit, he then raised the issue in the House of Commons as can be seen in over two pages of Hansard (viz. for non-British readers – the official minutes of Parliamentary proceedings). However, all of these efforts came to nothing. Two days before the local government elections, Mr Nicholas Ridley the then Secretary of State, announced that Airlink would terminate 4 months following the completion of the M25 motorway. Competition for the Airlink helicopter was confined to surface traffic on the M25 motorway. Soon after Airlink began, Green Line Coaches commenced a new service called Speedlink connecting Gatwick and Heathrow. This high-frequency coach service had to contend with the severe congestion on the M23 and M25 motorways. Studies showed that the M25 traffic flow far exceeded the planned design criteria. Frustrated from the beginning by the environmental lobby, its three lanes were hopelessly inadequate. Late in the day, the government ordered an extra lane to be built. These road works, lasting over many years, caused even worse congestion and millions of tons of polluted air from lorries and cars at a standstill to drift in the prevailing south-westerly wind over London. For many years after the cessation of Airlink, transfer between the two airports by road could not be guaranteed to any timetable and even today, one accident can block the motorway for hours.

Epilogue

During its eight years of operation, the Gatwick/Heathrow Airlink carried 600,000 passengers conveniently and speedily between the two airports. It became established as the crucial link in the London airports interlining strategy. It was both popular and efficient. The interlining benefit to British Caledonian Airways and British Airways ran into tens of millions of pounds; the interline revenue for the London airports amounted to £100million. It truly fulfilled its function. Like many other brave British aviation ventures, it failed because of political interference based on misinformation or worse. The recent Davies Airports Commission (2013) decided that a new Airlink inter airport helicopter transfer could not be justified as there was no evidence of a market!! The late Laurie Price, following his retirement having spent over 40 years involved in Air Transport Economics, Strategy and Policy, commented that he did not consider the Commission, which did not include even one commissioner with any experience in airline economics, marketing or operations, had done their research very well. Despite the change in market composition at Gatwick since Airlink ceased, the total passenger throughput at Heathrow and Gatwick has doubled and, according to CAA data, there are some 3 million transfer passengers a year at Gatwick, many of whom are connecting to and from Heathrow and who might prefer the guarantee of an unencumbered helicopter journey to succumbing to the vagaries of the M25, particularly when a bus transfer costs circa £25 and taxi £100++. Some 18 months after the demise of Airlink, BCal had to give up the fight as Britain’s second airline and was taken over by British Airways. Margaret Thatcher’s friend, Lord King, had one less problem in their combined mission to privatise the state airline. I don’t suppose that Airlink’s considerable contribution to the profits of BCal would have saved the airline. However, BCal had one office at Heathrow whose staff issued tickets for BCal services. The supervisor of this office said that the day the helicopter service ceased it was as if someone had turned off a tap and they all but ceased to sell tickets on BCal services!

AND OF G-LINK?

A photo as sad as the Turner painting of “The Fighting Temeraire”

Roll of Honour

There follows a list of team members who worked extensively on the service. It is not exhaustive and there may be omissions who can be added by contacting the website. Personnel marked with an * were employed by BAH but transferred to BCalH when the contract changed hands. The list of everyone who served is long, partly due to the enthusiasm of so many to have their names included and this is just as it should be!

British Airways Helicopters – Airlink Staff during period 1978-1984

Pilots

Brian Taylor; Gerry Howie; John James; Paul Hammett; John Lutkin; John Humphrey; Alasdair Campbell; John Bamford; Keith Dunning; Simon Sullivan; Keith Dunning; Ken Brett; Alan Brew; Julian Verity; Peter Hounsome; Dave Prince*; Robin Morgan

Engineers

Harvey Pole – Station Engineer; Graham Short- Station Engineer ; Derek Hapgood*; George Chatwin; Ken Gazey*; Mark Lees; Bernie Young; Steve Jones; Reg Burnett; Derek Griffith; Tim Doddington; John Church; Chris Duff-Cole; Trevor Wilburn; Dave Carver; Dave Cook; Colin Wooton; Simon Gent*; Alan Jackson; Trevor James; Derek Paul; Tony Arnold; Arthur Spain

Secretaries

Frances Grant; Betty Wells; Sandra Groves

British Caledonian Airways – Airlink Staff during period 1978-1986

Airlink Agents

Sally Caine – Supervisor Suzanne; Taylor – Supervisor; Frances Thompson –Supervisor; Rozlyn Blackwell; Jeanne Williams; Cathy Jones; Gill Barnes; Paul Lacy; Dawn Shuter; Andrea Venton; Vanessa Edwards; Carol Feest; Sally Harper; John Palmer; Chris Spear; Karen Childs; Chris Elvery; Vicky Webster; Stephanie Hawkey; Fiona George

Airlink Facilitator

Bob Manning

BA Handling Heathrow – Airlink Staff during period 1978-1986

Geoff Fordham – Manager of Executive Aircraft Handling Unit BA; John Duncan; Jack Gelson; Roger Luft; Ron Couch; Nigel Maddocks; Sue Dance; Pamela Douglas; Mary Murphy

British Caledonian Helicopters – Airlink Staff during period 1984-1986

Pilots

Graeme Thomson – Chief Pilot; Peter Hounsome*; Frayne Coulshaw; Jake Walsh; Pat Bainbridge; Bill Wright; Gerry Howie*; Alan Brew*; Andy Nash; Dave Owen; Dave Prince

Engineers

Paul Hicks/Derek Hapgood* – Station Engineers; Ken Gazey*; Eric Hardacre; Albert Poulson; Steve Cooper; Terry Williams; Alan Jackson; Malcolm Power; Dave Matthews; Simon Gent*; Amjab; Dave Cook; Dave Johnson

Other staff who worked for short periods on Airlink but nevertheless made their contribution to its success

BAH

Ian Morrison; Pete Bramley; Tom Porteous; Digby Mackworth; John Keepe; Steve Stubbs; Mike Evans; Dave Ritchie; Dave Turner; Dave Bailey; John Hall; John Blanch; ? Gibb; Neil Charlton; Jim Booth; Tony Buckley; Dave Gilbert; Simon Sullivan; Roy Moxham; Greg Turner; Peter Dupon; Keith Dawson (who kindly filled in some of the above names); Sandy Macfarlane; Alan Stewart; Andrew Oxenford

Rotation Staff BCAL

Jane Austin; Sue Melbourne; Liz Blake; Melanie White; Sarah Grove; Marion Hewitt; Angela Russell-Croucher; Shirley Rose; Audrey de Sa; Gill Murphy; Debbie Green; Liz Leaver; Katy Kirkham; Pauline Hobbs; Sally Huggett; Maggie Carswell; Chris Warrington; Debbie Young; Tina Davies (or Davis); Lorraine Ferguson; Sharon Morley; Madeline Robinson; Jan Gardener; Sharon Thomson

Yet another illustration of the amazing S61N on the River Thames by Battersea Heliport in January 1967 – Captain John Millward instructing the author during his command course. The exercises were rejected take-offs and landings in water – necessary due to the limited performance of the S61 in the event of one of its two engines failing below certain low height and speed combinations. Our visit caused quite a stir among the passengers of passing pleasure cruisers. The original military version of this aircraft had much smaller sponsons (the outriggers either side of the fuselage). They contain airtight compartments, as well as the retracted undercarriage, to provide greater lateral stability to the helicopter in the event of a ditching. The civil version had larger sponsons installed as standard. The S61N aircraft used on long over water operations, such as oil rig support, had inflatable balloons along the outside edge of the sponsons to provide even greater lateral stability. Even so, the operations manual quoted a limiting wave height of 6 feet beyond which the aircraft might rollover.

BCALH ENGINEERS PREPARE A TEMPORARY REPLACEMENT FOR G-LINK. I THINK MALCOLM COWLARD IS VISIBLE TO THE LEFT. PHOTO SUPPLIED BY DEREK PAUL.

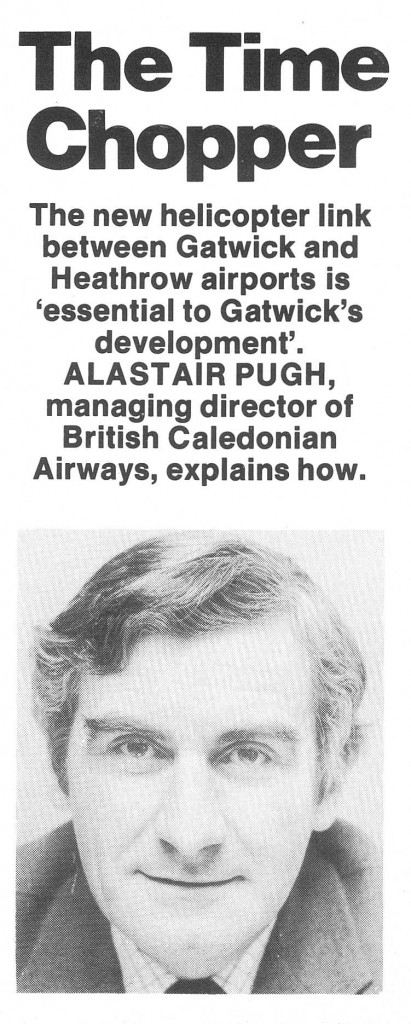

Lead article by Alistair Pugh, Managing Director of British Caledonian Airways in British Airports World – November 1978

EASY COME, EASY GO: The Sikorsky S-61N operates under special ATC procedures, operating virtually independently in and out of Heathrow. It uses the runway at Gatwick for less than half the time a fixed wing aircraft would require on a similar operation.

Exactly nine weeks from the date of inauguration, the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink helicopter service carried its 10,000th passenger. This traffic flow is well up to expectations and confirms the view held by the three joint operators – British Caledonian Airways (B.CAL), British Airports Authority and British Airways Helicopters – that a fast connecting service between the two major British airports was essential to Gatwick’s development. The Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink lifted off on June 9 this year, when the service was inaugurated by Prince Charles, who travelled on the helicopter from Gatwick to Heathrow. For the first full year of service, we budgeted on a load factor of 31 per cent -and in the first few months have actually achieved a figure of 30 per cent. If those figures appear low, let me point out that the very nature of the service, with free sale at overseas locations, means that we have to plan for seats always to be readily available. Even then there are substantial peaks of demand arising from the transfer of interconnecting passengers. Reaction has been encouraging. Business travellers in particular like the operation. Accolades have gone in particular to the helicopter’s regularity. So far, we have achieved an on-time performance factor of 97.42 per cent. The choice of equipment was sound. The Sikorsky S-61N – which is owned by the BAA – has proved its worth. It operates under special ATC procedures – a fixed wing aircraft of equivalent size would have to integrate with traffic flow at both airports. The helicopter can operate virtually independently into and out of Heathrow, and it uses the runway at Gatwick for less than half the time a fixed wing aircraft would require on a similar operation. When we came to plan the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink, we had to look carefully at its objectives. The service would, we decided, be primarily for the inter-airport transfer of interline passengers and their baggage; secondly, it would provide a substitute for the road journey to one or other of the airports for passengers starting their main air journey; and finally, it might carry fare-paying ‘joy-riding’ passengers when space was available after catering for the primary and secondary demand. It was agreed that it should be operated as a no-reservation, free-sale service with back-up capacity provided by chauffeur-driven cars and/or coaches. Priority for seats would be based on the time available to the interline passengers for their onward connections: those with the least time should have precedence. Once the helicopter was filled, passengers would be offered either a following flight or ground transport, as licensing restrictions prevented us from offering back-up helicopter services. Operationally, we planned that the link should operate as a domestic service with international passengers clearing controls inbound and outbound as if entering or leaving the UK. Baggage has to be cleared through Customs inbound and checked-in for outbound flights with which a connection is made. This ‘blueprint’ plan put the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink into service, once an operating licence had been granted by the Civil Aviation Authority. Over several months’ experience, we have been maintaining a close scrutiny of the operation, looking for ways and means of streamlining the service to passengers. We are already evaluating a system which will eventually enable international-to-international ‘through’ baggage to be checked over London to the next place of disembarkation: such baggage will be handled in bond, airside-to-airside, either by road or helicopter, greatly simplifying the transfer process.

It is not envisaged that international-to-international passengers will either need or be able to remain airside, because we want to continue to accommodate local passengers on the service. In any event, there are significant passenger dispersal and’ collection problems to be overcome at Heathrow before airside transfer arrangements could be made Other areas for action under review include: • Developing ways of providing free sale for all seats, with back-up by car or coach. Such a system is essential where no reservations system can be provided for international-to-inter-national passengers; and it is equally desirable for passengers wishing to use the service for personal transport from one airport to another where no interline transfer is concerned. • Introducing improved transfer arrangements at Gatwick via the new central airside transfer desk. This will make passenger registration and baggage identification easier when bonded baggage transfer becomes possible. • Reviewing the current Gatwick gate and stand arrangement (Gate 1H and Stand 1 are used at present) and considering an improved and exclusive gate arrangement for the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink. This plan goes hand-in-hand with proposals for new taxi and take-off procedures now being discussed with Air Traffic Control. The new operation has brought its share of complaints about noise, and we are taking very seriously the interests of the communities over which it operates. The routeing is kept under close review -we are checking the complaint record to see if there is anything more that we can do to keep the intrusion of the helicopter service on our neighbours to a minimum. The helicopter service was seen as crucial to the planned development of Gatwick, and also to the maintenance of London’s position as Europe’s Number One air gateway. It is rapidly achieving its original objective of making Gatwick and Heathrow ‘one’ airport. Before the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink, the transfer options were limited and time-consuming. BCAL operated a courtesy limousine service for its own connecting passengers, but this was unable to cope with the rapidly increasing traffic between the two airports, given the strong growth of services from Gatwick over the last few years. Until the motorway link between Gatwick and Heathrow is opened in the early 1980s, the helicopter link’s 15-minute journey time provides the best connecting bridge. For the time being, however, the first year of operations is regarded as being a period of test and trial. The Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink results from a co-operative effort unique in aviation. Inspired and backed by the British Airports Authority, it is operated by BCAL, using the flightdeck crews of BAH, which handles helicopters at Heathrow. We operate 20 one-way flights daily, with B.CAL taking prime responsibility for the commercial management of the service. B.CAL is also responsible for overall day-to-day running of the service, provision of cabin crew and handling at Gatwick. British Airways provides flight crews, technical support and the maintenance of the helicopter and handling facilities at Heathrow. Expectations are that the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink will carry a total of 60.000 passengers in the first 12 months, 48 per cent being generated by B.CAL. This bears out the British Government’s Airports Policy White Paper, in which Gatwick’s build-up was acknowledged to depend largely on the provision of greatly improved interline connecting services. Such services were regarded as essential to attract both passengers and airlines to the newly-developed airport and thereby make full use of the recent £100 million investment by British Airports at Gatwick. B.CAL has consistently felt penalised by the lack of a full range of interline service connections at Gatwick. Despite our efforts to foster the development of an increasing range of scheduled service connections into Gatwick, the range of interline connections from Gatwick remained inferior to those available from Heathrow – by a factor of one to four – in destinations served. But BAA also made it strongly known that it believed in the need for a better balance in the distribution of airline services between Heathrow and Gatwick. In this BAA was supported by the Government in its policy of aiming to achieve transfers of traffic from Heathrow. BAA’s efforts are progressing steadily and successfully, and the Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink has played its part. At the time of the licence application to the Civil Aviation Authority, we said: ‘The British Airports Authority sees the need for good inter-airport links as part of the Government’s plan to build up air services at Gatwick. Airlines consistently indicate to BAA the need for fast, frequent interlining facilities as a reason for not transferring to Gatwick from Heathrow.’ The Gatwick-Heathrow Airlink is a hop in the right direction.

SOME FORMER AIRLINK PILOTS AT ONE OF THE AIRLINK REUNIONS ORGANISED BY BETTY WELLS – Left to Right – Alasdair Campbell, the author, John Humphrey, Peter Hounsome, Robin Morgan, Dave Prince and Alan Brew

THE SAME GUY AT 75 YEARS, WITH WIFE, MARGARET, (SADLY NOW DECEASED) CRUISING ON THE NORFOLK BROADS AT 4 INSTEAD OF 121 KNOTS, STILL DODGING THE GRIM REAPER

An excellent and informative article, many thanks!

I think I can fill in some of the missing BAH names: Dave Bailey, John Hall, John Blanch, Neil Charlton, Jim Booth, Greg Turner, Tony Buckley, Peter Dupon. Moxam is a mystery I’m afraid.

And I made a modest contribution on occasions in ’83 and ’84 with detachments from Aberdeen….including an early morning ILS on 28R when the expected fog clearance didn’t – and realising when established that the published overshoot was out to Booker or thereabouts, not very practical with the Link fuel load and a mighty incentive to get visual by DH.

Best wishes, and thanks for the memories, Keith Dawson

Dear Keith – how lovey to hear from you, a former colleague. I hope this email finds you and your family well. Many thanks for the names. I will include them and yours with a special mention of your contribution. As regards the LHR approach, can you put this into an anecdote suitable for inclusion under your name, or anonymous if it was too dodgy an experience. I would be happy to include it.

With best wishes

Bill Ashpole

One small correction to this excellent article, Bill; HRH Prince of Wales didn’t open the North Terminal when he inaugurated Airlink. That was done by HM The Queen almost exactly ten years later. June 1978 was 20 years after The Queen opened the airport in 1958 and Charles toured the extensions to the South Terminal.

A minor detail in an article which taught me things I wasn’t aware of, even though I was involved on the fringes.

Best of luck

David Hurst

Public Relations, British Airports Authority, Gatwick.

Dear David

How lovely to hear from you after all this time. I hope you are well and enjoying life. It would appear from your signature that you are still working. Well done! I retired 13 years ago and can thoroughly recommend retirement.

Many thank for you correction. I will alter the text and make mention by name of your input.

Wishing you well in all things

Kind regards

Bill

Hello Bill

I was lucky enough to do 1 weeks leave relief in about 1981 although without the required route specific line check my contribution was as a copilot. It was a welcome (and my only) respite from 9 years of North Sea flying. However as a 777/787 pilot I am trying to do all I can to sustain your pensions.

Regards

Sandy Macfarlane

Hi Sandy – Great to hear from you and learn that you are still flying. Your name is now included – my apologies for the omission. I guess you did not appear in my log book and you were not on Betty Wells’ list. Please keep my two BA pensions topped up! Kind regards Bill Ashpole

Hi Bill

I just came across this article which has brought back many fond memories.

I am still in aviation handling VIP aircraft at Heathrow. We still handle the odd helicopter but off airport on private sites due Heathrow landing charges being a tad high.

Take Care

Regards

Roger Luft

Manager Private Aviation Services Heathrow

Dear Roger

How lovely to hear from you after all this time. Thank you for your kind comments on the article. I have tried to set down the history as best as I can remember it before too many of my brain cells (I am now in my 76th year) die!

As you can see, I, and others who have contributed to the article, cannot remember all the names of the guys at Heathrow. Can you assist? Please review the role of honour and fill in the gaps.

If you have anything else to add to the article, particularly any anecdotes, please feel free to pass them on. I will include them in the article with due accreditation to your good self.

I was delighted to see that you are still employed in aviation. It is good that the industry can still benefit from your massive experience.

Kind regards

Bill

[Other personal comments sent via email]

Hi Bill

Came across your site after looking for photos of G-LINK. Thanks for an excellent article. It certainly brought back many happy memories, a shame it all had to end.

I’m still working on helicopters. When I found out Harvey Pole, George Chatwin & Tim Doddington had come down from Shetland to join the team I never in a million years thought I’d end up there myself!

I’ve been up here in Sumburgh for 20 years now on the Coastguard SAR Unit, initially on the venerable S61N then the S92A from 2007 enjoying every minute.

Glad to hear you are still on the go, thanks again for taking me back many years.

Look after yourself

Best Regards

Steve

Hi Steve – great to hear from you and glad you enjoyed the article. Please feel free to send any additions to it. I will give you full accreditation.

Generally, I don’t envy anyone but will make an exception in your case. I really would love to be doing S & R – perhaps the best heli job ever.

Kind regards and safe flying. Bill Ashpole

I was one of the founder Engineers brought down from the Shetlands and I have a photo of G_BFPF a B.C.A.L. helicopter being prepared as the first Airlink in 1978 . I can send by e-mail if required

Regards

Derek Paul

Hi Derek – great to hear from you. Yes please – send the photo and I will include it with any comments you might wish to make relevant to the photo or anything other to do with Airlink. The website works well with jpeg photo format but may be able to cope with other formats.

Kind regards

Bill Ashpole