Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

My decision to leave the employ of Bristow Helicopters was taken at a time when the cyclical pattern of glut and famine in the pilot market was heading for a peak. All the world’s airlines were recruiting and I had job offers from Air Canada (who actually sent tickets) and Trans Australia Airlines and from helicopter companies including the helicopter division of British European Airways or BEAH. I decided to stay with helicopters and joined BEAH at Gatwick in May of 1966. The pilots based there were Captains’ Jock Cameron – the Managing Director, Doug Pritchard – Commercial Manager, Dave Eastwood – Operations Manager, and Second Officer, Tom Price. The first three of these gentlemen were former Viscount pilots seconded from the Airline. I joined as a First Officer and was quickly checked out on the S61N based at Gatwick for occasional charter work and leave relief at the other two bases, Penzance in Cornwall and Beccles in Suffolk.

Blood from a stone

My first two weeks were spent at Farnborough. BEAH, having recently acquired the S61N, was keen to exploit its capabilities to the full. There was some potential to improve performance criteria over and above that published by the manufacturers, Sikorsky of Connecticut, USA. This was done with the approval of the Air Registration Board, responsibilities later taken over by the Civil Aviation Authority. A team of BEAH personnel proceeded to Farnborough to perform a series of trials to demonstrate the aircraft’s capabilities during single engine rejected take-offs and go arounds. The aircraft was flown very precisely in minimum wind conditions and the trajectories were traced using kinetheodolites. The results were used to produce performance charts and figures that were then used for future BEAH/BAH operations and also, when they re-equipped with the aircraft, Bristow Helicopters. The new performance figures and graphs squeezed the final ounce out of the S61N using techniques which would be ideal for the Penzance heliport with its limited rejected take-off distance.

BEAH S61N PERFORMANCE TRIALS – TOP ROW: Mike Holt – Operations; Don Butler – Performance boffin; Author; unknown Farnborough guy; Captain Dave Eastwood – Flight Operations Manager; Gareth Jones; Bottom Row: Frank Atkinson – Engineering; Harry Bedford – Engineering; Second Officer Tom Price

BAH Gatwick – Jock Cameron with some of his team Don Huggett, Tom Price, Muir Parker, Betty Ballard, Don Courtenay, Bill Ashpole Mike Evans, Ian Wansborough, Jock Cameron, Russell Keefe, Fred Charlton – photo courtesy of Don Huggett

The S61N is considerably larger than the Whirlwind, had two engines and a seating capacity for 28 in a small airliner style of cabin. It is a two pilot aircraft, a legal requirement because of its weight. However, a second pair of hands is essential if only for adjusting the engine speed/torque levers situated to the rear of the top of the central windscreen. BEAH had started life as the BEA Experimental Helicopter Unit and then developed into a company. In 1963, Jock had somehow persuaded the Board of British Airways to purchase two S61N helicopters. This was no mean achievement and is entirely to his credit and dogged persistence as a helicopter visionary. The Penzance/Isles of Scilly scheduled helicopter service commenced in 1964 and replaced the Dragon Rapide biplane which used to fly from Lands End airfield. The other machine was destined for the North Sea and the base at Ellough airfield near Beccles in Suffolk for use in support of the offshore gas exploration industry. Both of these projects were, at the time, highly speculative only adding to Jock’s powers of persuasion. The choice of the Sikorsky S61N was also a masterpiece of good judgement. Alan Bristow went for the twin-engined Wessex, a mistake. To his credit, he quickly re-equipped with the S61N a few years later.

My very first commercial flight with BEAH was with the boss, Jock Cameron. The task was to fly to the island of Jersey for the annual Battle of Flowers. We flew low over the crowded main street and the cabin attendant, Wynn Jones, who threw hundreds of flowers out of the baggage hold door onto the public. We then flew on to Penzance where the helicopter was needed for the scheduled service. The manager of the service then was Captain Ron Dibb, who was one of the pilots of the BEA Helicopter Experimental Unit, the forerunner of BEA Helicopters Ltd. which then became British Airway Helicopters. Malcolm Dibb, son of Ron Dibb, kindly wrote and his notes are contained in the section Penzance/Scillies under “Comments”. They contain some interesting history and are well worth reading.

The Russians pay us a visit

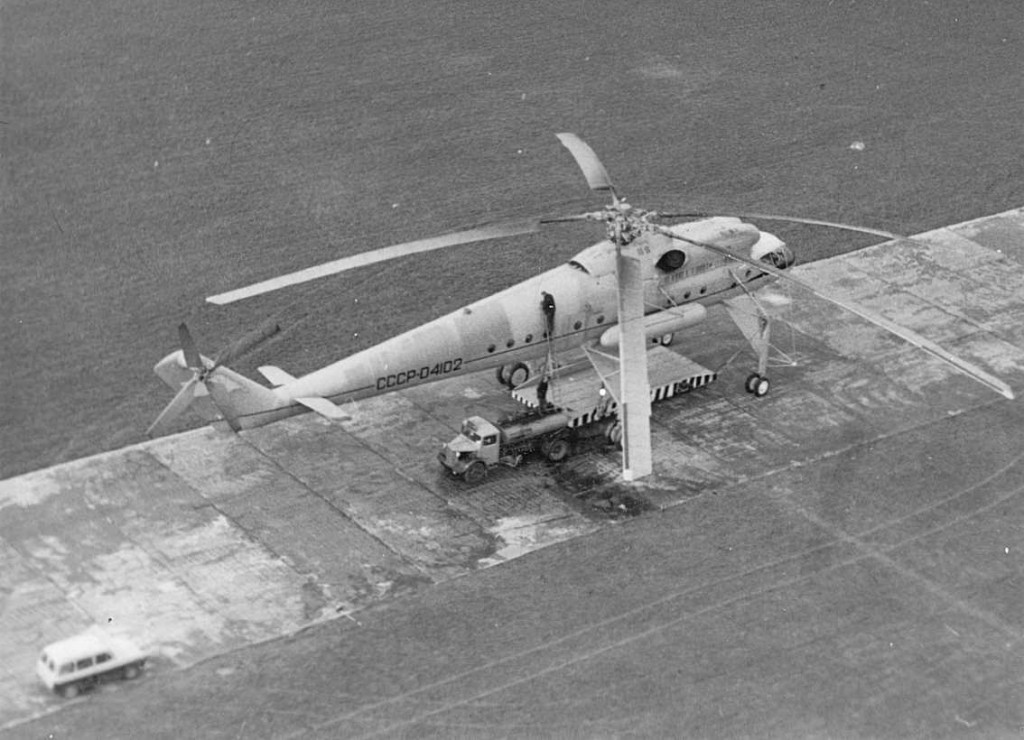

In 1967, Aviaexport, the marketing arm of the Russian aerospace industry, sent a Mil-10 helicopter on a sales tour. It flew into Gatwick on 12 March 1967 and BEA Helicopters was asked to be the host. It arrived with numerous staff on board, none of whom had a good command of English. Tom Price and I were detailed to fly on board to operate the radios. This whole episode on 12th to 14th March 1967 was an interesting experience. The Russians seemed to be a friendly bunch in spite of the fact that we were in the midst of the Cold War. The Mil-10 was a huge machine, impressive at every angle. It could sit over a motor coach. The Russians wanted to demonstrate its lifting capability by picking up and then flying a bowser full of fuel. The CAA were not impressed and permission was adamantly refused. During one flight they did pick up a lorry using the underslung hook. I told them that on no account could they fly over housing and other buildings. This was either misunderstood or ignored and we flew over the nearby town of Crawley with the lorry swinging in the air! The cockpit had a seat for the captain*, one for the co-pilot, another for the radio operator and at least two other seats. Not that seating mattered; at one time I counted no less than 9 men in the cockpit. *In Russian helicopters the captain occupies the left hand seat as per aeroplanes. This is the opposite to helicopters manufactured in the Western World. No one knows the reason why this aberration exists in the West. One explanation and the one that I prefer is that having mastered the machine sitting in the left hand seat, the original test pilot refused to swap seats in order to train other pilots!

Their attitude to flight safety was a world away from that in the West. Although the Mil-10 was a flying crane (the Mil-6 being the fuselage version), the cabin of the aircraft was larger than that of the S61N. It contained a kitchen table and chairs, numerous jerry cans of fuel and a few boxes of Vodka, none of which was secured to the floor. The Vodka was offered between flights and occupants smoked freely. Access to the aircraft was via a long metal ladder secured to one of the undercarriage legs. The cockpit dashboard included a TV screen which displayed the load underneath the belly of the aircraft. Apart from a hook for picking up loads, it also had a platform which could be secured to the helicopter by four vertical struts. The vehicle or whatever having been driven onto the platform, the four struts were attached and the platform was then drawn upwards until just clear of the belly of the aircraft. One evening, Tom Price and I, courtesy of our wives, invited a dozen of the Russian team to dinner at our bungalow in Haywards Heath. We had a convivial evening, probably in the company of the political representative who, we were told, was an essential companion to any Russian overseas mission. Driving to and from our home they were captivated by the cats-eyes in the road and surprised at the absence of pedestrians along the roads.

I was standing one day in the aircraft and experiencing a pronounced “woompah” (a vibration once per revolution of the main rotor caused by an aerodynamic tracking or mass imbalance problem). As we swayed from side to side I asked one of the Russians “Do all Mil-10 helicopters vibrate like this?” He answered with an absolutely straight face “Vot vibration?” I also enquired as to the performance of the helicopter if one engine failed “Russian engines do not fail!” was the reply.

Relations were so cordial that I was invited to try my hand at hovering the beast. I spent 10 minutes in the company of Captain Zemskov wrestling the stick which required considerable force to move. Although it had powered controls, there appeared to be a very strong spring mechanism to prevent sudden or large displacements, presumably to avoid the possibility of sending the huge rotor blades, which had a chord akin to a Chipmunk wing, into convulsions! One gained an impression that this was a remarkable aircraft, built to an impressive scale with a huge lifting capability. The engineering was less refined than the build of the typical Western helicopter, (akin to a Klingon Bird of Prey rather than the Star Ship Enterprise), but there it was, an amazing machine which did the job and we, in the West, had nothing remotely matching its capability. One of their team, a comrade Nikrasov, was a designer. He kindly gave Tom and me signed copies of his book on helicopter aerodynamics – in Russian of course.

Captain Boris Zemskov in the port seat with me in the starboard seat prior or after my hovering session, with co-pilot Karapetian Gurgen in the P3 seat

Below is a Pathe-News video of the visit. A very young author can be seen in the right hand seat after having a go at hovering.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/russian-helicopter-demonstration/zmfcy9q

And here is another by AP and starts with the young BEAH First Officer

Mil – 10 team with BAH personnel. Co-pilot Karapetian Gurgen, Captain Boris Zemskov, Fred Charlton (Chief Engineer BAH), another Russian, Bill Newey (BAH Engineering), Another Russian, Captain Dave Eastwood (Operations Manager BAH), another Russian and Captain Mike Evans (BAH)

See Helicopter World article on the Russian visit at end of this section.

Underslung at Liverpool

The company, through the Research & Development section of its Engineering department had government approval for modifications to the aircraft and ancillary equipment. One such project, lead by an engineer called John Wilding, was to develop an improved underslung load hook to exploit the capabilities of the S61 with its ability of lifting over 2 tons. The device that John developed was a rectangular frame bolted to the underside of the hull at four strongpoints with a system of cables free to move on pulleys so that the hook attached to the cables always hung in the ideal position. This mechanism gave a smooth flight even with the load swinging around. John Wilding would often fly with the aircraft and act as crewman guiding the handling pilot over the intercom. The pilots in the cockpit of the S61 sit well forward of the centre of gravity of the aircraft under which, of course, the hook is located. For this reason it is necessary that a crewman, with his head protruding from the cargo door several feet to the rear of the captain’s seat, gives guidance by giving simple directions such as : “forward 30..20..10..: right 6…5…4..: down 4…3…2 etc.” until the aircraft is in the desired position over the load. One of my memorable trips as a co-pilot was with Tom Price. It lasted from 2nd October to 5th 1966. The Mersey Docks and Harbour Board had a requirement to replace a marine marker situated on Hilbre island a few hundred yards off Meols Parade on the promenade at Liverpool. The police asked that we arrive at any time except midday on Sunday when the public tended to crowd the area. Due to inclement weather our departure was delayed and we arrived within 60 seconds of midday! There were hundreds of people in the area and the helicopter created a stir to the point that the ice cream vendor did so well that he gave us free ice creams. The police had to keep back the crowd to enable us to perform the underslung load operation. Tom picked up the marine marker, as shown in the photograph, and we proceeded offshore. The triangular pyramid of the marker had to be lowered onto a wooden guide pyramid and then bolted in place to the base which was already in situ. Unfortunately, something was wrong and at one stage the marker was jammed onto the base and we could not disentangle it even pulling maximum torque – a most unhappy situation and one with no future! Suddenly we broke free and were able to return to the Parade with the marine marker still on the hook. Apparently, the fittings on the base were not compatible with those on the marker. Some speedy engineering work by the customer fixed the problem and three days later the lift and installation went without a hitch.

William Press/SEGAS underslung loads

BEAH secured a contract with William Press who had been contracted by SEGAS to lay 280 pipes across a marsh near Eastbourne. The whole Gatwick complement of pilots were involved in this lengthy operation. Each cycle of picking up the load, ferrying it to its final resting place and then returning for another pipe took approximately 4 minutes so the whole job needed some 19 hours of flying not including positioning from and to Gatwick. It seemed an age until the enormous pile of pipes seemed to diminish in size! To our great surprise our efforts were rewarded with an envelope containing a tip!

The photograph below is by courtesy of Enrico at AviaFora. I recommend a viewing of his website which contains many excellent and interesting photographs of helicopters.

Back to piston engined Whirlwinds When I joined BEAH at Gatwick they had two piston engined Whirlwinds, registrations G-AOCF and G-ANFH, one of which was immortalised by Airfix who produced a small plastic kit model. The other four pilots, who were captains, (Tom Price having received his command), all flew these two aircraft on charter work. I owe my first command, albeit as a mere first officer, to Jock Cameron’s in-laws! Jock was scheduled to fly one weekend carrying a film crew following the Offshore Power Boat Race in the English Channel. This clashed with the visit of his in-laws and I heard an interesting argument between Jock and Dave Eastwood insisting that he, Jock, was the only one available to fly this charter. “Why can’t he (pointing to me) fly it?” retorted Jock. “Because he is not checked out!” replied Dave. “Check him out then!” said Jock. And that is how I first came to fly in command of a BEAH helicopter. In fact it was Jock himself who did the checking and in the next two days I completed the 1179H final check and visited the CAA for the type to be added to my licence.

I could argue that my masters were working on the principle that if I could survive the Offshore Power Boat Race then I would be capable of performing any task which came up. I don’t know what rules govern helicopter filming of this event today but in my day there were few and I was the only helicopter in the sky above the race. Now the S55 with metal floats, as shown in the photograph above, is quite heavy even with no fuel or passengers. It is also a drag-master! I set off on 3 September 1966 and headed for Cowes on the Isle of Wight to pick up the film crew from Stronghold Films. We were at maximum all up weight with the three man film crew on board with their equipment and sufficient fuel for following the race and reaching Portland then Torquay. I had dispensation from the CAA to ignore the minimum height rule of 250 feet above any vessel or person and did what was wanted by the film team, namely to fly very low over the racing vessels. In fact, we flew so low that the noise of the helicopter was drowned out by the noise of the individual power boats as they bounced across the surface of the sea at maximum speed. It was exhilarating flying!

My arrival at Torquay was even more memorable! The refuelling point was on a cricket field in a valley in the town of Torquay. Ricky Richardson, one of the BEAH engineers and quite a character, was waiting with a 45 gallon drum of AVGAS (aviation petrol). The lower I descended on the approach, the less the wind due to the geometry of the valley. This was going to be a tricky landing with insufficient power in hand. Approaching the hover and desperate to achieve a controlled descent, I “over-pitched” – a cardinal sin in which one allows the rotor rpm to drop below the 199 vital to hover a loaded piston engined S55. If the rpm drops to 198 then it is impossible to restore the speed to 199 unless one lowers the lever: but lowering the lever increases the rate of descent! I could not risk reducing speed to a hover as that would have cost me the little translational lift I had so I did a “run on” landing and ground to a halt. In fact the “landing” was a series of hard bounces that left me wondering if anything had broken off. I climbed down from the cockpit fully expecting to see something bent or lying on the ground thus bringing an end my career with BEAH. But no! – the beautiful machine was still in one piece in spite of the abuse it had suffered at my hands.

Various missions with the S55

An annual event was to despatch an S55 as the casevac helicopter for the Isle of Man TT Motor Cycle Races. Ricky Richardson, our intrepid engineer, set off with me from Gatwick. We arrived at Liverpool Speke airport. The helicopter landing area was very remote from the control tower where I needed to report. No problem! Ricky arrived in a few minutes with a borrowed pedal cycle and off I went. During my few days covering the TT Races there were, mercifully, no serious accidents. One of the traditional annual duties of the helicopter pilot was to join with the local Member of Parliament and a former TT champion to judge the beauty contest. Well someone has to do it!

From time to time we had charters for various VIPs including ferrying senior management of British Airways.

BEAH were given a contract by the CAA/ARB to fly some 300 hours with an oil lubricated rotor head. Hitherto, it was standard for helicopters to have grease lubricated bearings in the rotor head necessitating frequent attention with grease guns. Bert Westerman, our accountant at Gatwick, took it upon himself to organise tickets for hundreds of Gatwick staff to be flown in G-ANFH. These flights were very popular. Joy rides were another activity and it was just possible to make a small profit at such events as fairs and country shows. The S61N was also used for the charters including VIPs, as the following photograph shows.

There is an apocryphal story of Jock Cameron joy riding at an air show with the S61. “Quick, Pat, get the passengers off and another lot on!” “But Captain Cameron, this lot have not yet had their flight!” He was always one for keeping his eye on profit!

The Instrument Rating – this section was shared between my time at Gatwick and Aberdeen

BEAH/BAH more than any other helicopter company of its era was an innovator, both in flight operations and engineering. The Engineering Department under Chief Engineer, Fred Charlton, had Design Approval – the authority to modify aircraft and have those modifications certificated by the CAA and ARB. Dave Eastwood, as Manager Flight Operations, led the way in developing a Helicopter Instrument Rating, something that no other helicopter operator in the Western world had pursued. It is possible that the Russians had done so but probably not. The driving rationale was the need to operate in the majority of the weather to be found over the North Sea, thus giving our oil industry customers a more reliable service.

Dave decided that the best way to proceed was to model the helicopter rating on the well-established aeroplane instrument rating of which, as a former Viscount pilot, he had vast experience. The project was pursued in close cooperation with the Flight Operations Inspectorate section of the CAA*, headed by Jeff Gurr and assisted by his deputy, Tony Lister. The S61N had VOR/ILS and ADF as well as the Decca Navigator. VOR and ADF were the standard aids in use at the time for navigating airways and conducting VOR or NDB cloud break procedures and for alignment for ILS and GCA approaches. (VOR – Very high frequency omni-range and direction navaid; ILS – Instrument Landing System – the ICAO standard precision landing aid for the World’s airfields; NDB – non-directional radio beacon; GCA – ground controlled approach – talk down by air traffic controller used mostly by the military at airfields but also,at that time, at major airports, even Heathrow).

I had learnt to fly aeroplanes and helicopters on instruments during my flying training with the RAF. Whilst on 225 Squadron we were further checked and I held a Transport Command “Master Green” Instrument Rating. With the very basic navigation equipment of the Provost T11, the Vampire T11, the Sycamore and the Whirlwind, instrument flying was confined to handling the aircraft using the instruments available to maintain the correct attitude (pitch and roll), altitude, airspeed and heading. Lack of navigational instruments meant we had no means to determine the position of the aircraft over the ground. Occasional bouts with the Decca Navigator were short-lived as the equipment was soon removed. Navigation was by Dead Reckoning (the pilot calculated a heading, ground speed, sector time and fuel needed based on the forecast wind at the chosen altitude). Arrival at the destination airfield depended on the services of Air Traffic Control providing a radar approach such as a GCA (Ground Controlled Approach) or an SRA (Surveillance Radar Approach). The former gave altitude and heading to steer to place the pilot some 5 miles away from the threshold of the runway in use but on the extended centre line. Then the radar controller would pass corrections to heading and recommended heights, to give the pilot guidance to maintain the glide slope and centre line all the way down to the Decision Height – the minimum height approved for the approach. The controller might say “you are left of the centre-line and should be passing through 1,200 feet”, etc. The the controller was blind to the actual height of the aircraft. At the Decision Height, the pilot would either have descended below the cloud base and been able to look up and land visually or, if still unable to see the approach lights, would have to initiate a climb and carry out a missed approach procedure under the direction of the radar controller. The GCA was more sophisticated in that the controller had height information and was able to advise the pilot that he was “above the glide-path, left of the centre-line, etc. so providing, as it were, a talking instrument to enable the pilot to fly all the way down to the Decision Height for the procedure, which was always lower than that for the SRA.

Now the civil instrument rating is very different in that, apart from obtaining clearances from Air Traffic Control, the pilot must not only handle the aircraft but is also responsible for navigation down to the Decision Height using the instruments in the aircraft linked to the various navigation aids on the ground, namely, VOR, NDB and ILS.

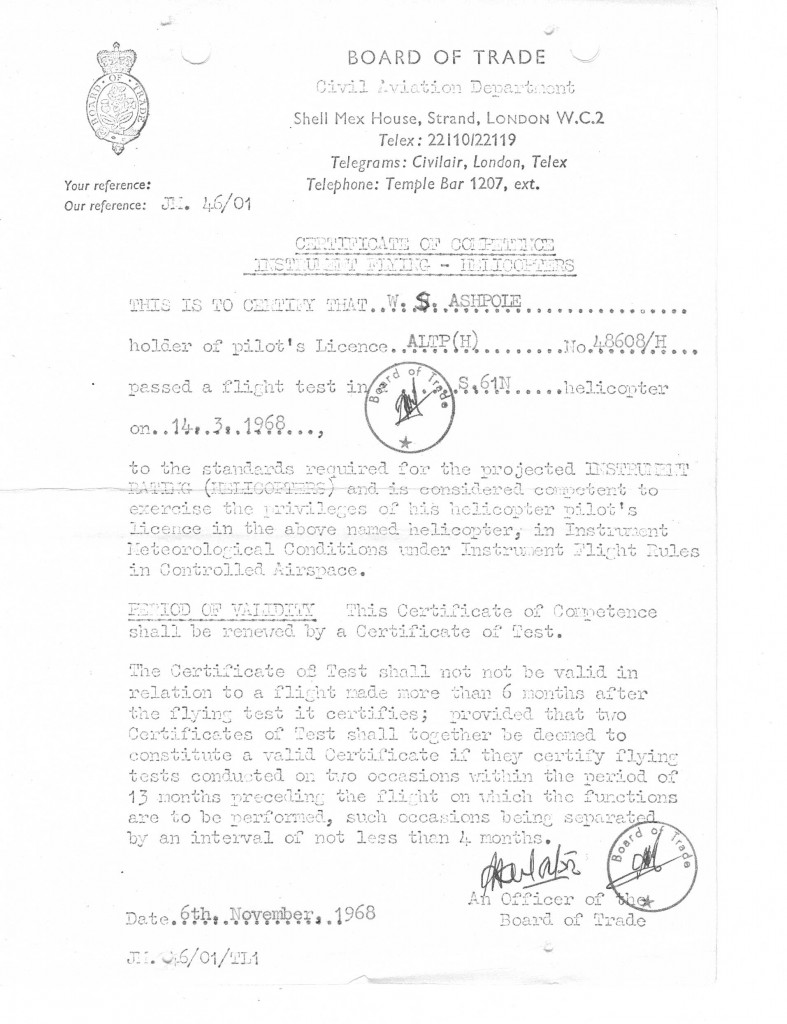

Next to BEAH in the Beehive building at Gatwick was Tony Mack’s company offering a Link Trainer. We spent a few hours in this very basic device which allowed one to brush up on instrument flying skills and learn airways flying using NDB’s and VOR’s. Route over the “ground” was plotted on a table by a moving box with a set of tricycle wheels powered and steered via a cable. The instructor could see how the student was adhering to the required track. Progressing to the S61N, a system of panels was clipped to the cockpit windows in front of the pilot being taught or tested who wore headgear to complete the block off from the outside world limiting vision to cockpit instrumentation alone. Piloting the S61N on instruments, even with the AFCS (Automatic Flight Control System) functioning and maintaining the pitch, roll and heading selected by the handling pilot with the stick and rudder pedals and definitely NOT an automatic pilot which maintains the height, heading and airspeed as dialled by the pilot), required great skill and concentration. In addition to merely flying a fully serviceable helicopter, it was part of the Instrument Rating test to include an equipment failure such as an engine failure or, in the case of the S61N, an AFCS failure or a failure of one of the hydraulic systems which powered the jacks which controlled the rotors. It was considered to be too much of a challenge for one pilot unaided. The helicopter instrument rating was progressed to fruition on the basis that although one pilot would handle the controls, the other pilot would be available to handle communications and operate the speed levers, undercarriage, etc. as directed by the handling pilot and as called for by the cockpit checks. On 14 March 1968 I underwent the test at Aberdeen having been posted there in February. Dave Eastwood was my co-pilot. Tony Lister sat on the jump seat between us and was the examiner. Jeff Gurr, Head of Flight Operations Inspectorate Board of Trade Civil Aviation Department, stood behind Tony and was checking Tony out as an examiner!! Tony Lister was checking out Dave Eastwood. It could be likened to a Keystone Cops movie! The same day Dave Eastwood passed his test as did Tony Lister.

*N.B. In the account on my website I have mentioned CAA (Civil Aviation Authority) and ARB (Air Registration Board). However, government organisations change from time to time. In fact, the authority at the time of gaining my certificate of competence to fly on instruments was awarded by the “Board of Trade”. Some of my earlier pilot’s licences bear the name “Ministry of Aviation”. So, I ask my readers to allow me some licence in this matter.

Transcript of Certificate of Competence (including typo of 2 “nots” in the last paragraph) BOARD OF TRADE Civil Aviation Department Shell Mex House, Strand, London W.C.2 Telex: 22110122119 Telegrams: Civilair, London, Telex Telephone: Temple Bar 1207, ext Your reference: Our reference: JM. 46/ 01 CERTIFICATE OF COMPETENCE INSTRUMENT FLYING – HELICOPTERS THIS IS TO CERTIFY THAT W. S. ASHPOLE holder of pilot’s Licence. ATPL(H) No 48608/H passed a flight test in a S61N helicopter on 14. 3. 1968 to the standards required for the projected INSTRUMENT RATING (HELICOPTERS) and is considered competent to exercise the privileges of his helicopter pilot’s licence in the above named helicopter, in Instrument Meteorological Conditions under Instrument Flight Rules in Controlled Airspace. PERIOD OF VALIDITY This Certificate of Competence shall be renewed by a Certificate of Test. The Certificate of Test shall not not be valid in relation to a flight made more than 6 months after the flying test it certifies: provided that two Certificates of Test shall together be deemed to constitute a valid Certificate if they certify flying tests conducted on two occasions within the period of 13 Months preceding the flight on which the functions are to be performed, such occasions being separated by an interval of not less than 4 months. Date 6th November 1968 JM 46/01/TL1 [Signature and stamp over] An Officer of the Board of Trade

Anecdotes It has to be said that some of these founder members of BEAH were characters and I include here some anecdotes which will amuse those who still remember these individuals. Margaret Goodall, a former colleague at the Beehive sent me these two. #1 I shall never forget going to meet a helicopter at Gatwick one evening with Doug Pritchard and Dave Eastwood flying it, and one of the engineers asking some technical question and their reply: “in the darkness and the terror we didn’t notice!” #2 It involved Mike Perkis, Doug Pritchard and Tom Price (I think) flying the S61 when the Torrey Canyon went down off Lands End. One of them needed to relieve himself and there was only a jerrycan on board. At the crucial moment, one of the crew on board signalled the pilot and he made the aircraft “wobble”!

Single Pilot Clearance for the Helicopter Instrument Rating

Although the S61 was a 2 pilot machine as regards the Instrument Rating, I have learnt from an old friend from Bristow’s, Jean Dennel, (station engineer for the Bristow operation in Bushire close to Kharg island who later became a very senior figure in Bristow’s engineering department) that Alistair Gordon drove through a project to obtain single pilot clearance on instruments for the Bell helicopter. This necessitated some additional electronics to provide some stabilisation to relieve pilot workload. A remarkable achievement on the leading edge of helicopter history.

FLYING THE GIANT RUSSIAN HELICOPTER – AN ARTICLE PUBLISHED IN HELICOPTER WORLD APRIL 1967 A Multi-Author Feature Incorporating the Experiences of British Pilots who flew and flew in the Russian Mi-10  THE RUSSIAN demonstration of their giant Mi-10 crane helicopter, at Gatwick last month, was an event of no little importance in the helicopter world. It was the first time that a Russian helicopter had ever flown to England and they certainly set the ball rolling in a big way. For some of its visit the Mi-10 was based at BEA Helicopters’ Gatwick Airport South base, where it occupied a large part of the grass operating area alongside the “Beehive”. The energy developed by its 115 ft. diameter rotor was evident in the strength of its downwash which blew over many of the barriers that had been placed around the edge of the tarmac area. It even blew over some of the photographers who ventured on to the grass to picture the massive machine as it took off or came in to land. The helicopter was flown by Captain Boris Zemskov, Chief Test Pilot at the Soviet Aviation Ministry, who has been flying helicopters for 12 years. His fixed wing experience dates back to 1959 and he has completed some 7,000 hours total. Flying the giant crane is a 2-pilot operation and he was assisted by Co-pilot Karapetian Gurgen, a test pilot with the Mil Institute. The latter was able to speak quite good English but in view of the volume of air traffic around Gatwick and their lack of familiarity with British r/t procedure, it was felt advisable to have an English pilot to operate the radio communication with Gatwick air traffic control, this job being shared by B.E.A. Captain T. J. D. Price and 1st Officer W. S. Ashpole, both of B.E.A. Helicopters Ltd. On some of the flights they performed this task in the co-pilot’s seat and were invited to handle the controls themselves for short periods. Their impressions are included later. The demonstration was arranged by Aviaexport, the Soviet overseas trade bureau, and it had a two-fold purpose. On the one hand, the Soviet Union have reached a stage in helicopter development when they are anxious to find overseas’ markets for their helicopters in addition to those already being supplied in their immediate neighbours. They also want to gain experience of British airworthiness requirements as they appear to be thinking in terms of designing for export to British certificate of airworthiness standards. For this latter reason, a proportion of the time spent in England was devoted exclusively to giving representatives of the Air Registration Board free run of the machine to let them make a preliminary assessment of its characteristics. In charge of the trade delegation which accompanied the helicopter to England was Mr. Mikhail Lebedev, the helicopter Department Manager of Aviaexport. He caused a good deal of amusement at the conference following the flight demonstrations by starting his speech of welcome through an interpreter and then lapsing into English—which he spoke quite well—half way through. He spoke about the Soviet wish to sell helicopters in the European market and provided some interesting figures on costs, the first authentic information on this subject to be published outside the Soviet Union.

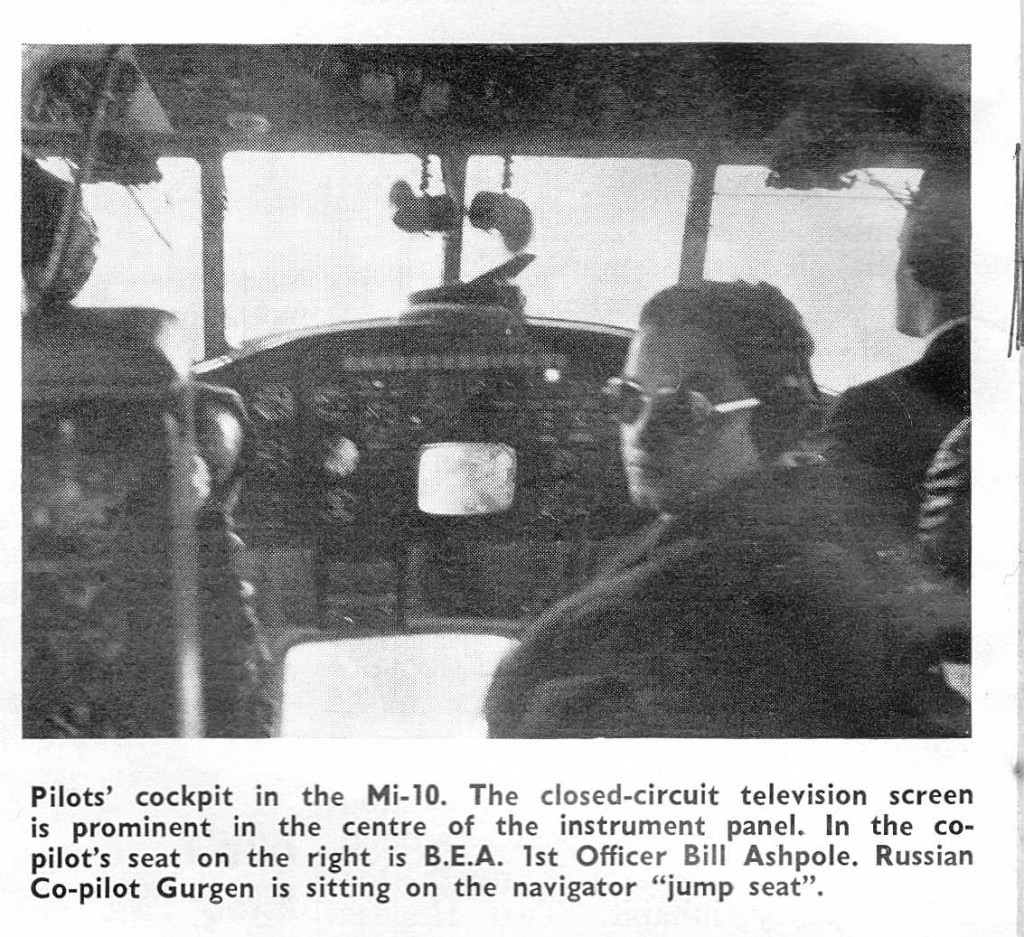

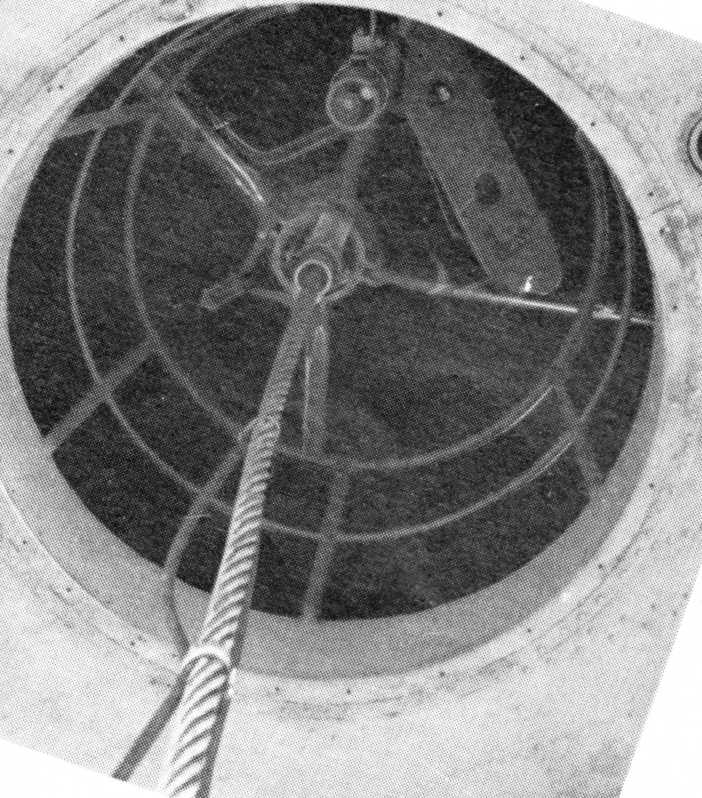

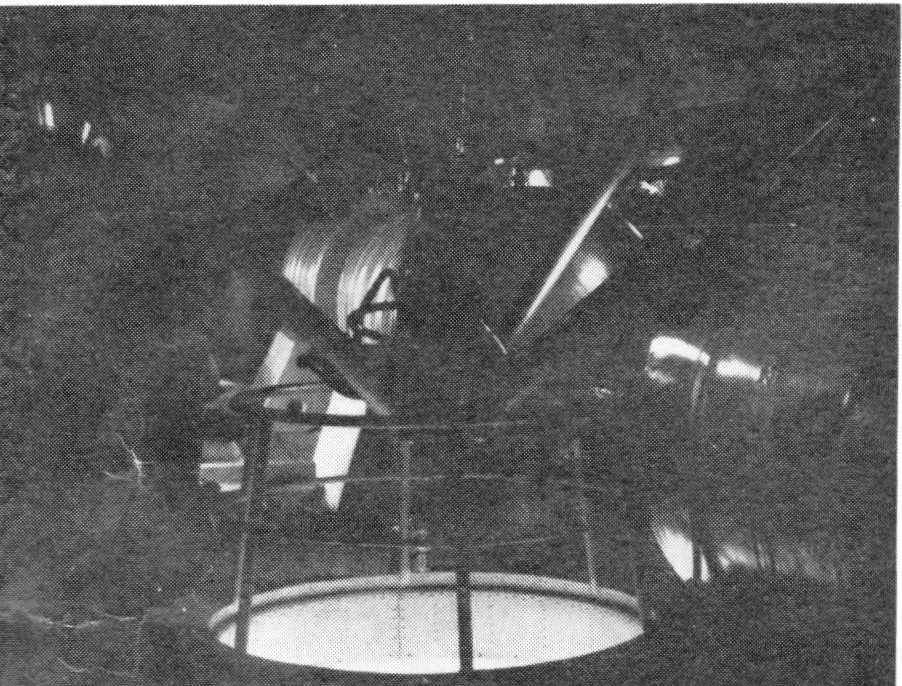

THE RUSSIAN demonstration of their giant Mi-10 crane helicopter, at Gatwick last month, was an event of no little importance in the helicopter world. It was the first time that a Russian helicopter had ever flown to England and they certainly set the ball rolling in a big way. For some of its visit the Mi-10 was based at BEA Helicopters’ Gatwick Airport South base, where it occupied a large part of the grass operating area alongside the “Beehive”. The energy developed by its 115 ft. diameter rotor was evident in the strength of its downwash which blew over many of the barriers that had been placed around the edge of the tarmac area. It even blew over some of the photographers who ventured on to the grass to picture the massive machine as it took off or came in to land. The helicopter was flown by Captain Boris Zemskov, Chief Test Pilot at the Soviet Aviation Ministry, who has been flying helicopters for 12 years. His fixed wing experience dates back to 1959 and he has completed some 7,000 hours total. Flying the giant crane is a 2-pilot operation and he was assisted by Co-pilot Karapetian Gurgen, a test pilot with the Mil Institute. The latter was able to speak quite good English but in view of the volume of air traffic around Gatwick and their lack of familiarity with British r/t procedure, it was felt advisable to have an English pilot to operate the radio communication with Gatwick air traffic control, this job being shared by B.E.A. Captain T. J. D. Price and 1st Officer W. S. Ashpole, both of B.E.A. Helicopters Ltd. On some of the flights they performed this task in the co-pilot’s seat and were invited to handle the controls themselves for short periods. Their impressions are included later. The demonstration was arranged by Aviaexport, the Soviet overseas trade bureau, and it had a two-fold purpose. On the one hand, the Soviet Union have reached a stage in helicopter development when they are anxious to find overseas’ markets for their helicopters in addition to those already being supplied in their immediate neighbours. They also want to gain experience of British airworthiness requirements as they appear to be thinking in terms of designing for export to British certificate of airworthiness standards. For this latter reason, a proportion of the time spent in England was devoted exclusively to giving representatives of the Air Registration Board free run of the machine to let them make a preliminary assessment of its characteristics. In charge of the trade delegation which accompanied the helicopter to England was Mr. Mikhail Lebedev, the helicopter Department Manager of Aviaexport. He caused a good deal of amusement at the conference following the flight demonstrations by starting his speech of welcome through an interpreter and then lapsing into English—which he spoke quite well—half way through. He spoke about the Soviet wish to sell helicopters in the European market and provided some interesting figures on costs, the first authentic information on this subject to be published outside the Soviet Union.  Cost of the Mil-10 crane helicopter and the Mi-6 passenger version, fitted as an 80-seater, would be approximately the same—in the region of £600,000. The smaller Mil V-8, the 30 seat twin turbine machine that was evaluated by B.E.A. Captain J. A. Cameron, in Moscow last month, was said to cost $625,000 or approximately £225.000. No price could be given for the 8-passenger Mil V-2 but the Mi-4, which is an earlier design slightly larger than the Wessex and powered by a single piston engine, was said to cost £50,000. Aviaexport also deal with other Russian helicopter constructors, apart from the Mil Institute, and Mr. Lebcdev said that the cost of the new Kamov KA-24 would be a little over £30.000 plus the cost of special equipment that could be fitted. The KA-24 is a small co-axial rotor utility helicopter that can be fitted for crop-spraying, rescue work and as an aerial ambulance. In reply to a question, he said that the other Russian helicopter team, originally led by Yakovlev, were designing a new 30-passenger twin turbine helicopter due for service in 1969 but no details are available yet. Presumably this type will be based on the tandem rotor configuration to which Yakovlev have adhered for most of their projects. Technical information supplied at the conference by Mr. Andrew Nekrasov, Assistant Chief Designer at the Ministry of Aviation Industry in Moscow, amplified considerably the previous knowledge of the Mi-10 particularly and also other Russian helicopters. Advance information on future projects he gave included the news that Mil are working on an 80-passenger version of the Mi-6 that would be capable of completing the London-Paris run, city-centre to city-centre, in 1 hour 20 minutes. It was an interesting insight into their present thinking, incidentally, that the performance of this machine was related specifically to the London-Paris route, as opposed to the selection of a typical Russian route as an example. This new helicopter will be exhibited at the Paris Air Salon, it was said. In addition, the Russians are developing a new version of the Mi-10 for use more specifically in civil engineering construction work. It will have shorter undercarriage legs and a third pilot’s control position facing aft. The co-pilot will be able to move to this position during lifting operations and fly the machine while looking directly at the load he is raising or lowering on the hoist. This, of course, is a feature of the Sikorsky S-64 crane helicopter. Flying in the Mi-10 was an exceptionally interesting experience. The world’s largest helicopter, it is a two-pilot operation to fly it and because of this it was not possible to handle the controls. However, it was possible to obtain some indication of the handling characteristics, standing in the cockpit behind the two pilots. Normally the co-pilot occupies the right-hand seat but-because of the language difficulty and the volume of air traffic in the Gatwick Airport circuit, B.E.A. 1st Officer Bill Ash-pole flew with the machine during the flight demonstrations and sat in this seat to maintain constant r/t communication with air traffic control. The Russian 2nd pilot used a “jump seat” in the centre gangway, from where he performed the various co-pilot duties during the run up, take-off and landing phases. Entry to the machine is gained by way of a stairway incorporated in the port undercarriage leg and its supporting members, to a door on the port side. This opens into a small compartment from which one door gives access into the cockpit itself and another into the rear cabin. For the series of long range flights associated with the recent series of demonstrations by the machine, four large fuel tanks had been installed in the cabin (the reserve fuel provided a range of just over 600 miles). The tanks occupied a good deal of the space in the cabin but there was still room for some 30 people at a time to fly in the machine. Bench seats along each side of the cabin are fitted but, since the machine is not designed as a passenger carrier, there was no upholstery and no air conditioning. The rear cabin was thus rather noisy and hot but this was only to be expected. Any helicopter without furnishings is the same. It was interesting to note, though, that the Russians do not seem to bother about seat belts for passengers. In fact, part of the seating accommodation in the rear cabin comprised an ordinary “kitchen” table, unsecured, with a number of small tubular frame chairs. The pilot’s cockpit, in contrast is both ventilated and soundproofed so that conditions here are comparable to other aircraft. As might be expected in such a large machine, the cockpit is big enough to be described as the flight deck. Behind the pilot’s and co-pilot’s positions are seats for the (light engineer on the left and the radio operator on the right of the gangway. The most unusual feature is the closed circuit television screen located in a prominent position in the centre of the pilots’ instrument panel. This is primarily to provide the pilot with a sight of any load he may be lifting or lowering on the cable hoist which is secured to the main structure below the rotor pylon in the rear cabin, through an aperture in the cabin floor. The pilots can also use the picture as an indication of the position of the main wheels relative to the ground while landing. The camera is located in the tail, viewing forward. The other instruments on the panel, although of unfamiliar design, were self-evident as attitude and compass indicators, together with height and airspeed indicators. The machine is fitted with power controls in all four channels and has a complete auto-pilot system. All the engine instruments are grouped together at the flight engineers position. The controls themselves are of conventional pattern, comprising stick, rudder pedals and collective pitch lever with twist grip throttle. In flight, the vibration present is by no means unacceptable. Considering the size of the helicopter, its intensity is relatively low. There is a certain amount of rather ponderous fuselage “stir” on the long undercarriage legs during the period of rotor engagement, but this soon settles down when the rotor gets up to speed. Rotor speed, incidentally, is in the region of 130 r.p.m.—much slower than in more familiar machines because of its great size. B.E.A. Pilot’s Impressions Describing his and Captain Price’s impressions of the Mi-10, 1st Officer Bill Ashpole writes as follows: In keeping with the rest of the Mi-10 the cockpit is vast; during certain of the flying demonstrations at Gatwick up to nine people managed to crowd the flight deck. The Captain and Flight Engineer sit in tandem on the port side: the Co-pilot and Radio Operator similarly to starboard. The central gangway between the pilots has ample space for the unsecured navigator’s stool. In spite of the machine’s size, the cockpit is surprisingly clear of complication. Each pilot has the normal blind flying instruments, radio compass and rotor and engine tachometers (in per cent.). A systems failure indicator panel and a minimum of other instruments leave the panel fairly free for the occasional switch and the closed circuit television screen. The flight engineer’s panel contains nearly all the aircraft’s temperature and pressure gauges and a large bank of switches is convenient to his left hand. A dial type vhf multi-channel selector is one of the few items I recognised in the roof panel over the pilots; the radio operator has WT as well as normal vhf communication. The atmosphere in the cockpit was at all times very informal with little evidence of any spoken checks. With the APU already running, one of the pilots would throw two switches and both engines would slowly run up. The start of rotor engagement was almost imperceptible and the acceleration continued gently up to the region of 85% rotor speed (indicated) which was maintained throughout flight.

Cost of the Mil-10 crane helicopter and the Mi-6 passenger version, fitted as an 80-seater, would be approximately the same—in the region of £600,000. The smaller Mil V-8, the 30 seat twin turbine machine that was evaluated by B.E.A. Captain J. A. Cameron, in Moscow last month, was said to cost $625,000 or approximately £225.000. No price could be given for the 8-passenger Mil V-2 but the Mi-4, which is an earlier design slightly larger than the Wessex and powered by a single piston engine, was said to cost £50,000. Aviaexport also deal with other Russian helicopter constructors, apart from the Mil Institute, and Mr. Lebcdev said that the cost of the new Kamov KA-24 would be a little over £30.000 plus the cost of special equipment that could be fitted. The KA-24 is a small co-axial rotor utility helicopter that can be fitted for crop-spraying, rescue work and as an aerial ambulance. In reply to a question, he said that the other Russian helicopter team, originally led by Yakovlev, were designing a new 30-passenger twin turbine helicopter due for service in 1969 but no details are available yet. Presumably this type will be based on the tandem rotor configuration to which Yakovlev have adhered for most of their projects. Technical information supplied at the conference by Mr. Andrew Nekrasov, Assistant Chief Designer at the Ministry of Aviation Industry in Moscow, amplified considerably the previous knowledge of the Mi-10 particularly and also other Russian helicopters. Advance information on future projects he gave included the news that Mil are working on an 80-passenger version of the Mi-6 that would be capable of completing the London-Paris run, city-centre to city-centre, in 1 hour 20 minutes. It was an interesting insight into their present thinking, incidentally, that the performance of this machine was related specifically to the London-Paris route, as opposed to the selection of a typical Russian route as an example. This new helicopter will be exhibited at the Paris Air Salon, it was said. In addition, the Russians are developing a new version of the Mi-10 for use more specifically in civil engineering construction work. It will have shorter undercarriage legs and a third pilot’s control position facing aft. The co-pilot will be able to move to this position during lifting operations and fly the machine while looking directly at the load he is raising or lowering on the hoist. This, of course, is a feature of the Sikorsky S-64 crane helicopter. Flying in the Mi-10 was an exceptionally interesting experience. The world’s largest helicopter, it is a two-pilot operation to fly it and because of this it was not possible to handle the controls. However, it was possible to obtain some indication of the handling characteristics, standing in the cockpit behind the two pilots. Normally the co-pilot occupies the right-hand seat but-because of the language difficulty and the volume of air traffic in the Gatwick Airport circuit, B.E.A. 1st Officer Bill Ash-pole flew with the machine during the flight demonstrations and sat in this seat to maintain constant r/t communication with air traffic control. The Russian 2nd pilot used a “jump seat” in the centre gangway, from where he performed the various co-pilot duties during the run up, take-off and landing phases. Entry to the machine is gained by way of a stairway incorporated in the port undercarriage leg and its supporting members, to a door on the port side. This opens into a small compartment from which one door gives access into the cockpit itself and another into the rear cabin. For the series of long range flights associated with the recent series of demonstrations by the machine, four large fuel tanks had been installed in the cabin (the reserve fuel provided a range of just over 600 miles). The tanks occupied a good deal of the space in the cabin but there was still room for some 30 people at a time to fly in the machine. Bench seats along each side of the cabin are fitted but, since the machine is not designed as a passenger carrier, there was no upholstery and no air conditioning. The rear cabin was thus rather noisy and hot but this was only to be expected. Any helicopter without furnishings is the same. It was interesting to note, though, that the Russians do not seem to bother about seat belts for passengers. In fact, part of the seating accommodation in the rear cabin comprised an ordinary “kitchen” table, unsecured, with a number of small tubular frame chairs. The pilot’s cockpit, in contrast is both ventilated and soundproofed so that conditions here are comparable to other aircraft. As might be expected in such a large machine, the cockpit is big enough to be described as the flight deck. Behind the pilot’s and co-pilot’s positions are seats for the (light engineer on the left and the radio operator on the right of the gangway. The most unusual feature is the closed circuit television screen located in a prominent position in the centre of the pilots’ instrument panel. This is primarily to provide the pilot with a sight of any load he may be lifting or lowering on the cable hoist which is secured to the main structure below the rotor pylon in the rear cabin, through an aperture in the cabin floor. The pilots can also use the picture as an indication of the position of the main wheels relative to the ground while landing. The camera is located in the tail, viewing forward. The other instruments on the panel, although of unfamiliar design, were self-evident as attitude and compass indicators, together with height and airspeed indicators. The machine is fitted with power controls in all four channels and has a complete auto-pilot system. All the engine instruments are grouped together at the flight engineers position. The controls themselves are of conventional pattern, comprising stick, rudder pedals and collective pitch lever with twist grip throttle. In flight, the vibration present is by no means unacceptable. Considering the size of the helicopter, its intensity is relatively low. There is a certain amount of rather ponderous fuselage “stir” on the long undercarriage legs during the period of rotor engagement, but this soon settles down when the rotor gets up to speed. Rotor speed, incidentally, is in the region of 130 r.p.m.—much slower than in more familiar machines because of its great size. B.E.A. Pilot’s Impressions Describing his and Captain Price’s impressions of the Mi-10, 1st Officer Bill Ashpole writes as follows: In keeping with the rest of the Mi-10 the cockpit is vast; during certain of the flying demonstrations at Gatwick up to nine people managed to crowd the flight deck. The Captain and Flight Engineer sit in tandem on the port side: the Co-pilot and Radio Operator similarly to starboard. The central gangway between the pilots has ample space for the unsecured navigator’s stool. In spite of the machine’s size, the cockpit is surprisingly clear of complication. Each pilot has the normal blind flying instruments, radio compass and rotor and engine tachometers (in per cent.). A systems failure indicator panel and a minimum of other instruments leave the panel fairly free for the occasional switch and the closed circuit television screen. The flight engineer’s panel contains nearly all the aircraft’s temperature and pressure gauges and a large bank of switches is convenient to his left hand. A dial type vhf multi-channel selector is one of the few items I recognised in the roof panel over the pilots; the radio operator has WT as well as normal vhf communication. The atmosphere in the cockpit was at all times very informal with little evidence of any spoken checks. With the APU already running, one of the pilots would throw two switches and both engines would slowly run up. The start of rotor engagement was almost imperceptible and the acceleration continued gently up to the region of 85% rotor speed (indicated) which was maintained throughout flight.

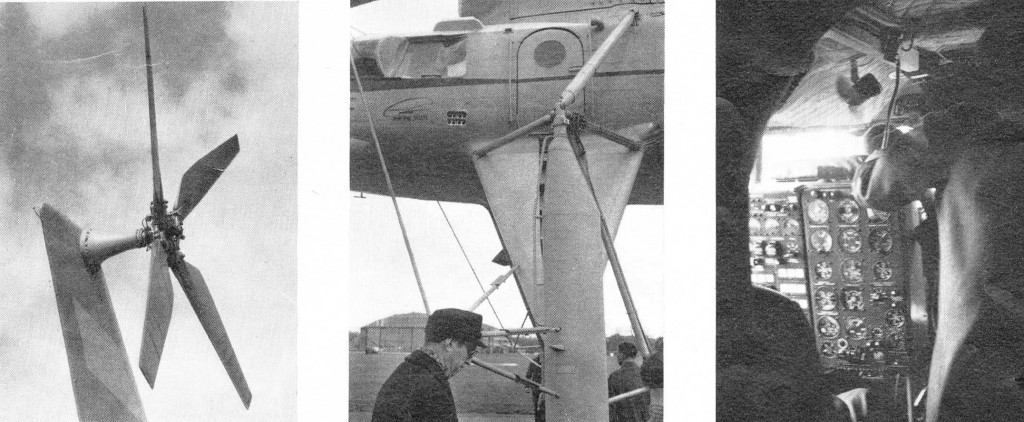

The picture above (left to right) the Mil 10 tail rotor, the access stairway to the forward cockpit and the flight engineer’s position in the cockpit. Note the soundproofing material on the cabin roof.

With the rotor engaged the machine had a noticeable (rotor) vibration. In spite of several attempts to breach the language barrier. I was unable to discover whether this vibration was inherent in the type or peculiar only to this particular machine. The flying controls, with the exception of the throttle, conform to Western practice. The throttle is in the form of the familiar twist grip on the end of a very short lever, but is rotated in a direction opposite to Western convention. Later Marks of Mil-10 have automatic rotor speed control. Releasing a button in the end of the throttle locks the lever in any desired position. It requires considerable force to overcome the spring bias of the cyclic control. This is probably a design feature to prevent large cyclic movements from sending the 57-foot rotor blades into convulsions! A beeper trimmer mounted on the top of the stick (as per S-61) provides assistance. The right hand arm rest of the Captain’s seat features a miniature stick for autopilot control. Rudder and lever control seemed adequate and due allowance had to be made with regard to the direction of rotation of the main rotor, which is clockwise when viewed from above. In forward flight 1 thought that the aircraft handled quite responsively if one could accept the effort necessary to move the stick and rudders. The usual approach made by the Russian pilots was long and flat, terminating in an extremely high hover. Once established in the hover it felt more stolid, its great mass unaffected by small wind gusts. The landing, usually performed by Captain Zemskov, was always very definite, there being a distinctly solid feel to the undercarriage. After engine shutdown, the rotor was allowed to coast almost to a standstill before application of rotor brake. The quality of picture on the television screen was worthy of note. With the coach in situ on the under-slung platform, the forward pointing cameras enabled the crew to detect any movement of the rear of the vehicle. Without the coach in position, one of these cameras with a long focus was used as a taxying aid to position the wheels into a confined area. There are also downward pointing cameras which look along the winch cable used for lifting the lorry. Actual positioning of the helicopter over the lorry was achieved with the assistance of a VHF “Walkie-Talkie” operated by a ground engineer. The pilot flying the aircraft during the “hook-up”, gave only an occasional glance at the television picture. Lack of depth perception limits use of the installation as a self-sufficient marshalling aid, but the ability to study the behaviour of the load in flight is a tremendous asset. My overall impression of the Mi-10 is one of admiration for this eight-year-old machine which combines impressive performance without too much sophistication. These impressions by two experienced British helicopter pilots confirm substantially our own impressions of the machine. There are some slight variations in the degree of importance attached to vibration but nothing beyond what might be expected from normal variations in individual’s opinions. Whether Aviaexport expect to sell the Mi-10 itself in the European markets is not completely clear. Its work capacity, with a payload capability of some 15 tons, is extremely high and to obtain economic utilisation its annual programme would probably have to be planned by some form of national authority. It would almost certainly be capable of more work than any single construction company could provide. Military utilisation would be a different matter, of course, but in this particular series of demonstrations it was not as a military aircraft that the machine was offered. Whatever the case, the Mi-10 certainly proved an impressive “standard bearer” for the Russian helicopter industry and its visit may well stimulate a good deal of interest in the other more conventional Soviet helicopters. Full technical data on the complete range of Russian helicopters will be included in our World Helicopter Number, next month.

With the rotor engaged the machine had a noticeable (rotor) vibration. In spite of several attempts to breach the language barrier. I was unable to discover whether this vibration was inherent in the type or peculiar only to this particular machine. The flying controls, with the exception of the throttle, conform to Western practice. The throttle is in the form of the familiar twist grip on the end of a very short lever, but is rotated in a direction opposite to Western convention. Later Marks of Mil-10 have automatic rotor speed control. Releasing a button in the end of the throttle locks the lever in any desired position. It requires considerable force to overcome the spring bias of the cyclic control. This is probably a design feature to prevent large cyclic movements from sending the 57-foot rotor blades into convulsions! A beeper trimmer mounted on the top of the stick (as per S-61) provides assistance. The right hand arm rest of the Captain’s seat features a miniature stick for autopilot control. Rudder and lever control seemed adequate and due allowance had to be made with regard to the direction of rotation of the main rotor, which is clockwise when viewed from above. In forward flight 1 thought that the aircraft handled quite responsively if one could accept the effort necessary to move the stick and rudders. The usual approach made by the Russian pilots was long and flat, terminating in an extremely high hover. Once established in the hover it felt more stolid, its great mass unaffected by small wind gusts. The landing, usually performed by Captain Zemskov, was always very definite, there being a distinctly solid feel to the undercarriage. After engine shutdown, the rotor was allowed to coast almost to a standstill before application of rotor brake. The quality of picture on the television screen was worthy of note. With the coach in situ on the under-slung platform, the forward pointing cameras enabled the crew to detect any movement of the rear of the vehicle. Without the coach in position, one of these cameras with a long focus was used as a taxying aid to position the wheels into a confined area. There are also downward pointing cameras which look along the winch cable used for lifting the lorry. Actual positioning of the helicopter over the lorry was achieved with the assistance of a VHF “Walkie-Talkie” operated by a ground engineer. The pilot flying the aircraft during the “hook-up”, gave only an occasional glance at the television picture. Lack of depth perception limits use of the installation as a self-sufficient marshalling aid, but the ability to study the behaviour of the load in flight is a tremendous asset. My overall impression of the Mi-10 is one of admiration for this eight-year-old machine which combines impressive performance without too much sophistication. These impressions by two experienced British helicopter pilots confirm substantially our own impressions of the machine. There are some slight variations in the degree of importance attached to vibration but nothing beyond what might be expected from normal variations in individual’s opinions. Whether Aviaexport expect to sell the Mi-10 itself in the European markets is not completely clear. Its work capacity, with a payload capability of some 15 tons, is extremely high and to obtain economic utilisation its annual programme would probably have to be planned by some form of national authority. It would almost certainly be capable of more work than any single construction company could provide. Military utilisation would be a different matter, of course, but in this particular series of demonstrations it was not as a military aircraft that the machine was offered. Whatever the case, the Mi-10 certainly proved an impressive “standard bearer” for the Russian helicopter industry and its visit may well stimulate a good deal of interest in the other more conventional Soviet helicopters. Full technical data on the complete range of Russian helicopters will be included in our World Helicopter Number, next month.

Hmm it looks like your website ate my first comment (it was extremely

long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say,

I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog. I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new

to the whole thing. Do you have any helpful hints for rookie

blog writers? I’d genuinely appreciate it.

Replied privately

This website truly has all the info I needed about this subject and didn’t know who to ask.

Woah! I’m really loving the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s challenging to get that “perfect balance” between user friendliness and visual appearance. I must say you’ve done a excellent job with this. Additionally, the blog loads extremely quick for me on Chrome. Excellent Blog!

michael jordan golf apparel

[url=http://www.bangornazch.org/?shop=michael-jordan-golf-apparel&id=6795]michael jordan golf apparel[/url]

Thank you Michael

You ought to be a part of a contest for one of the finest sites on the web.

I’m going to highly recommend this web site!

Thanks, Frances – you are very generous.

Pingback: British Airways used to operate a fleet of helicopters from 1964-1986 - FlyerTalk Forums

William, you asked for personal experiences or anecdotes on the home page, well I have one for you re the visit of the Russian Mi-10 to the Beehive at Gatwick in March 1967. I found your site because I was looking for any reference to this visit as I remember having a tour of it as a young boy of nearly 11. My father worked at the CAA’s Technical Engineering Establishment (TEE) just down from the Beehive. He came home one evening to announce that this Russian helicopter had arrived and they were letting people have a look. So he took me over there that evening and I can still recall going inside this strange thing for a tour. No flight, though from your report of the demonstration to the good citizens of Crawley, that was perhaps just as well. My interest to search for some reference to their visit was stimulated particularly by a recent visit to the Central Museum of the Airforce in Moscow where they have one on display. Happy to let you have a few photos from my visit there if you’d like to e-mail me.

Dear David – thanks for your message with its interesting comment. I am certainly interested on your photos and will send my email link. Best wishes. Bill Ashpole

P.S. TEE may still have been Board of Trade back in 1967?

Bill, thank you for a thoroughly interesting read and a nostalgia trip for me. I doubt you will remember me, John Miller. I joined BEAH engineering in November 1969 having recently left the British Army. It was a great outfit to work for, with some wonderful characters. We were very busy putting the 3rd fuel cell in the S61 fleet at that time. I christened us “The 3rd Tank Regiment, Charleton’s Own Reluctant Highlanders ” as even in those early days we were facing a move to Aberdeen. After 4 or 5 years in the executive helicopter world (Air Hanson and House of Fraser) I came back into what was now BAH to look after Ricky’s little baby G-AWGU (Agusta Bell 206) at Inverness. I finally left to join the CAA in 1990 by which time the company had suffered a sea change under the ownership of Robert Maxwell. However I cherish the memories of those early days with BEAH. Thanks again.

Hi John, Great to hear from you after all these years. You had an interesting history with BEAH/BAH and, like me, moved around. I smiled remembering Ricky – what a character! I think we all have some fond memories not least of which was the pride we felt in being “the best”! Helicopter operating and engineering history was made as we faced some very challenging issues. I don’t think that anyone who served deserved that awful man to buy the Company and rob the pension scheme! Best wishes Bill

Bill, like John above, I was an engineer but joined BEA Experimental Unit as a final year apprentice under Den Angel working in the instrument workshop. I stayed on as an instrument/electrical fitter working on the S55s and the Bells you mentioned and eventually the S61N gaining licences over the years for electrical/instruments/AFCS and compasses so we would meet frequently on compass swings. I came across your blog purely by accident as I was looking for a prewar picture of the Beehive and had to read it, it brought back vivid memories of the early days especially the Russian Mil 10 visit. Were you around when the Beetles visited BEAH at Gatwick, their visit gets a mention on the media occasionally? Thanks for the memories

Dear Arthur – Great to hear from you after all these years. I remember you from the days of Fred Charlton, Frank, Denis Angel, Don, John Wilding, Tony Short and all the rest – helicopter pioneers in every respect. The Beatles visit was before my time but I expect that Jock Cameron, Doug Pritchard, Dave Eastwood and Tom Price might have been involved with the flying. They were fun days with a couple of primitive machines, the S55’s, and then the S61N made a little better by our valiant engineering team who kept me alive and without serious technical mishap. I hope you are enjoying your retirement and look back on fond memories of Gatwick. Best wishes. Bill Ashpole

Dave Eastwood was my paternal grandfather. He died about about 15 years before I was born so never had the pleasure of meeting him, so these anecdotes and photos are particularly special. A thoroughly interesting and enjoyable read! Thank you.

My late father John Reid flew for BEAH from around 1955 until 1961 and I am trying to put names to faces in his photo album. He trained on the Bell 47B and then flew Sycamores and W.S55’s. I used to fly around the UK with him as a 10- to 12-year-old and have no problem recognising Jock Cameron but Dave Eastwood, Doug Pritchard and others I am unable to recognise. Not sure how to send a copy of some of the photos. Is there an email address?

Regards

Martin Reid

Wakefield

Nelson N.Z