Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

HELICOPTERS AND OIL EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION

One has to admire the skill and tenacity of the oil exploration and production industry, particularly those companies and individuals involved in the very hostile environment off the coast of England and Scotland. The gas and oil brought ashore has made an enormous contribution to the wealth of the United Kingdom and has thereby touched the lives of every inhabitant. Could it have been done without the helicopter industry? – Of course! But I venture to suggest that progress would have been much slower and many more lives would have been lost. Helicopters have played a vital role in the support of the oil and gas industry and the helicopter operating companies have had to be on the leading edge of operational and engineering development in order to face the arduous challenges, especially those of adverse weather. Very occasionally, the price has been very high in terms of human life as men and machine have lost the battle but this needs to be seen against the overwhelming success of millions of hours safely flown and men and equipment delivered to schedule. I, for one, am proud to have been associated with these men and their enterprise!

EARLY DAYS FOR THE HELICOPTER COMPANIES

Exploitation of the undersea wealth of the North Sea concentrated initially off the coast of East Anglia where gas was discovered. British Airways Helicopters set up a base at a former airfield, Ellough, near Beccles in Suffolk. Bristow Helicopters set up their own operation at Yarmouth. The BAH operation began with the Sikorsky S61N and the base remained active throughout the history of the company. The search for oil moved northwards and was based at Aberdeen in Scotland. Bristow Helicopters, followed by BAH, established bases at Dyce airport in Aberdeen in support of the considerable activity in search of oil.

A SEGMENT FROM OIL EXPLORATION AND PRODUCTION HISTORY ON THE NORTH SEA

Phillips Petroleum discovered oil in December 1969 in the Ekofisk field which is in Norwegian waters in the centre of the North Sea. Also in December, Amoco discovered oil in the Montrose field some 135 miles east of Aberdeen. British Petroleum had licences for the Montrose area but had not used them. Spurred on by the Amoco discovery, BP drilled a dry hole in May followed by striking oil in the Forties field in October five months later. The Forties field proved to be enormous. Shell Expro discovered the second enormous field, the Brent, situated in the northern North Sea to the east of Shetland to the north of the mainland of Scotland. The next discovery was by the Petronord Group – the Frigg gas field. Further discoveries were the Piper oil field in 1973 and the Stratfiord and Ninian fields in 1974. The Beatrice field in the Moray Firth was discovered in 1976. The actual production of oil began with the Argyll & Duncan Oilfields (subsequently renamed Ardmore) in June 1975 and the Forties oil field in November 1975. It took four years of drilling by BP to eventually find oil. In fact, it was by drilling deeper that they found the precious liquid. The result was dramatic! It seemed that the whole world descended upon Aberdeen. I was posted there from Gatwick in 1967 and paid around £6000 for a three-bedroom bungalow. For three years I wondered if I had paid too much for the property. Two years later, when I came to sell the bungalow, it went for around £15,000. Fifteen months later the new owner sold it for £25,000! These were crazy times and in sharp contrast to those which befell Aberdeen a few years later when the oil industry entered a period of recession. There were many very sad stories of homeowners in dire circumstances with huge negative equity. Fortunately, as with many industries, the wheel of fortune then turned and the oil industry in Aberdeen re-established itself!

THE BEA/BAH OPERATION

Initially, we operated out of the old passenger terminal at Dyce on the east side of the airport. It was nothing better than a large shed to which Portakabins were attached to cope with our passengers. However, this would soon have to change. The two helicopter companies had purpose built hangars constructed on the west side of the airfield and rotary wing operations soon far exceeded those by aeroplanes.

VERY SHORT FINALS FOR STAFLO – CAPTAIN MIKE EVANS AT THE CONTROLS WITH THE AUTHOR ON THE SPEED LEVERS

The British Airways Helicopters base at Aberdeen, like Bristow’s, grew continuously as more and more rigs arrived and more oilfields were developed. At the start, we only flew to the rig “STAFLO” for Shell UK, but later, contracts with other companies blossomed. Although “STAFLO” was our stable diet for the first four years we then gained further contracts with different oil companies and other names were added to our catalogue of destinations: OCEAN TRAVELLER, GRAND ISLE, SEDCO, TRANSWORLD 61, ORION, GLOMAR III, GLOMAR IV, 135F , 135G, 700B, P84, ZAPATA UGLAND, 700, PACESETTER 1 ,BREDFORD DOLPHIN, PIPER A, MCP 1, GULF TIDE, and many others.

The S61N was the mainstay of our fleet and proved itself to be an exceptional aircraft. That is not to say there was never a hitch. Captains Dave Creamer and Keith Gregson ended up on the sea in the early hours of 15 November 1970 when their aircraft, G-ASNM, experienced a loss of oil to the main rotor gearbox necessitating a ditching. Fortunately, they were soon picked up by a fishing vessel and the helicopter rolled over and sank to the bottom of the sea. (see Aberdeen Press & Journal article dated 16 November 1970 later in this section).

HAMILTON BROS. – UNDERSLUNG LOAD TRIALS

The first manager of the BEAH/BAH base in Aberdeen was Bob Simpson, a very pleasant man who died tragically in a road accident. He was replaced by Mike Evans who went on to become Director Flight Operations. BAH had a contract with Hamilton Brothers. A problem arose in transferring supplies by rig crane during rough weather conditions so the company sought to find ways around the problem. They proposed that their helicopter should be used to transfer supplies between the rig supply vessels and the rig. Bob kindly gave me the assignment to prove the feasibility. It involved hovering very low over the pitching and rolling supply vessels and lifting and lowering loads using the underslung load hook developed by our company. The project did prove feasible but was not used due to the introduction of greater flexibility in the use of the rig cranes.

THE WEATHER

Weather over the North Sea is legendary. There are many fine and sunny days but then there are days and days of cloud, wind and rain. Winds of hurricane force, especially to the north of Aberdeen and around the Shetland Isles, are to be expected. Shetland experiences winds in excess of 100 mph on average three times per annum. Wave heights of up to 100 feet have been known putting perspective on the amphibious capability of the S61N which will capsize in wave heights of more than six feet. Flying in such conditions can be rough, to say the least. The aircraft vibrates more than normal and the occupants get a shaking.

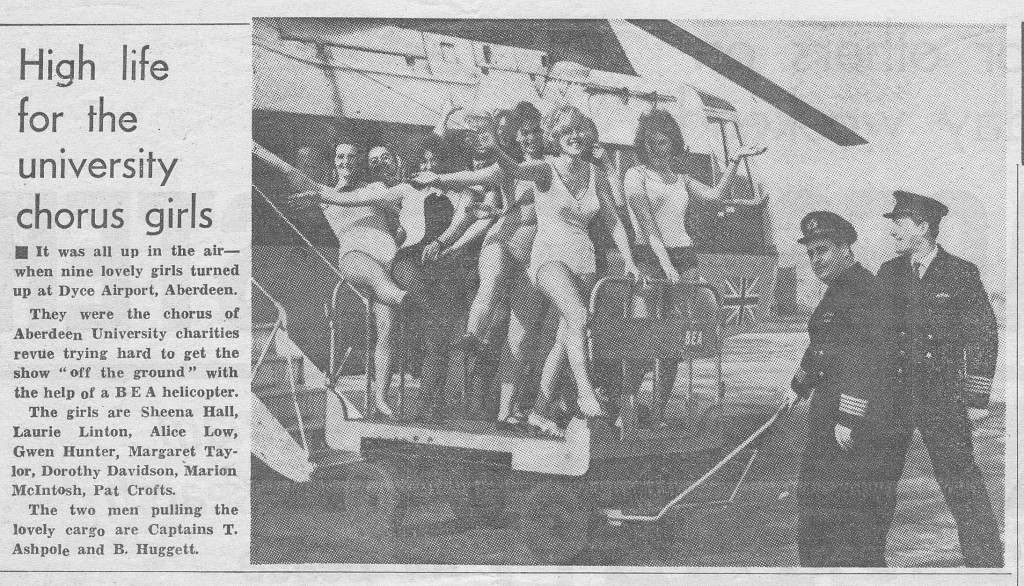

OCCASIONALLY WE WERE CALLED UPON TO PERFORM PHYSICALLY DEMANDING DUTIES! CAPTAIN DON HUGGETT AND THE AUTHOR

ICING CONDITIONS

Under the leadership of Captain Dave Eastwood, BAH pioneered with the CAA and ARB (Air Registration Board) a clearance to fly in forecast “light” icing conditions. This specified a rate of accretion of not more than half an inch of ice in 40 miles flying. The means of determining this was via a nine inch long metal aerofoil section – a metal rod – mounted on a box just outside of the captain’s window. The assembly included a light for use when night flying and a heated element for “burning” off the ice to begin a new check of accretion rate. Captain Dave Creamer was given the exciting task of further pursuing the icing clearance by flying in a variety of icing conditions. The S61 had windscreen de-icing by means of heater elements buried in the Perspex, the engine intakes and the first four rows of stator vanes (the non-revolving stages of the axial flow compressor) by means of a hot air bleed taken from the compressor, and electrical heating to the pitot head (the metal tubes which protrude forwards on all aircraft to provide a measurement of the kinetic pressure of the air and thus the airspeed). Neither the main nor the tail rotor blades had any form of de-icing except that kinetic heating due to the speed of the blades revolving through the air would warm the leading edges on the more outboard sections. Ice and snow could build up on the cabin roof over the cockpit. In those seasons when icing conditions were likely (visible moisture present, viz. cloud, mist or fog, in the temperature region +5 to -15 degrees Centigrade), an ice shield was installed to prevent ingestion of ice and snow, which may have built up on the front end of the cabin roof, into the engine intakes. This shield took the form of a flat plate angled to the cabin roof. Apart from the loss of power that the anti-icing systems caused, the other aspect of concern was knowing whether the systems were operating effectively. The only test one could apply to the intake and stator vanes was to switch the system on and off during checks after starting engines. If the system was working then one should see a small increase in power turbine temperature and a corresponding small decrease in compressor speed. This was not a very positive check and could not, of course, be repeated when in icing conditions. Sandy Sanders and I were flying on the airway between Aberdeen and Edinburgh when, at flight level 50 (5,000 feet) one engine flamed out. We returned to Aberdeen on the other engine, remaining in thick cloud all the way. Once on the ground, the engine that had stopped started readily as, by then, the ice had melted.

THE GLOMAR RIGS

My first flight to Glomar III took place on 29 May 1971. The Glomar series of rigs were converted whaling ships with a small helipad built onto the stern. Ships pitch and roll and so limits for landing were imposed. As I recall the roll limit was 2.5 degrees. Now landing with the nose towards the superstructure of the ship was straightforward in that one could see the obstruction of the bridge, etc. Thus the proximity to the nearest object to the rotor blades was clearly visible and there was ample visual reference to effect a safe landing. I always felt that a good guide to proximity was the eyeballs of the ship’s crew peering out at the helicopter! When one could see white all around their pupils then it was close enough to touch down! However, landing tail rotor towards the superstructure was something else. There was nothing to focus on to establish an accurate hover. So Captain Russ Williams, our company Flight Technical Officer, had the oil company erect long poles, with spheres on the end, around the helideck. This provided the visual reference needed and gave some measure of comfort that the tail rotor was not about to grind into the bridge of the ship! The Glomar rigs were by far the most challenging of all the rigs due to the location, size and movement of the helipad. Fortunately, they did not remain on the North Sea for long.

UNTETHERED RIG

Another rig which appeared for a spell, it may have been the Ocean Traveller, was one which was not tethered to the sea bed but was held in position by thrusters governed by satellite positioning and wind speed. During our first operation to this particular rig we were asked to fly slowly around in close proximity. We then received a frantic call to clear away immediately! Looking back at the rig one could see the sea churned to a white froth all around the rig. Apparently, the rotor downwash had been detected by the wind sensor on the rig and the rig positioning computer was trying to compensate for hurricane-force winds – hence the froth churned up by the thrusters trying to push the rig in every direction at once.

A STRANGE VIBRATION

On 16 August 1971, Brian Slade and I flew G-ATBJ to Edinburgh airport to pick up a drill bit. This object weighed around a ton and took considerable effort by many men to load it in the cabin of the S61N. They were working against the clock as the airport was due to close at midnight. We finally took off 45 minutes after Cinderella hour and climbed into the night sky heading North-East toward Aberdeen. As we levelled out a vibration began to shake the aircraft at a frequency of once per revolution of the main rotor (220 RPM). This was a bit eye-watering as main rotor and main rotor gearbox problems are the two most alarming technical problems that can be faced by helicopter pilots. Engine and tail rotor failures can sometimes be handled.

We conjectured that we had lost a piece of streamlining from one of the main rotor blades. Asymmetric icing could have produced the same vibration but we were in clear air with excellent visibility. Reducing main rotor RPM failed to rectify the problem so a return to Edinburgh seemed the only course available – but Edinburgh ATC had closed down. We gave a quick call to Scottish Flight Information and asked if they could catch Edinburgh before their staff had departed for the night. We were lucky and a safe return to Edinburgh was achieved without further incident, a flight duration of 30 minutes. The airfield shut again immediately after we landed.

Our engineers arrived from Aberdeen the next day but could find nothing wrong with the aircraft. As I recall, the oil company transported its drill bit by road, unable to wait any longer.

I can only conjecture that the drill bit, an unusually heavy but dense load, whilst having been secured well within centre of gravity limits, had caused some kind of harmonic vibration in the rotor/fuselage combination giving us the one per rev vibration.

SURVIVAL SUITS

Throughout my 17 years in BEAH/BAH we wore the standard captain’s uniform with the four gold bands on the sleeve. At some stage whilst at Aberdeen, the company supplied us with a survival suit in the form of a high-quality thick anorak with a drop-down piece of rubber which could be wrapped around the groin area. Wearing was optional and most pilots would drape the jacket over their seat for use should a ditching occur. Much later, and after I had moved to the Penzance/Scillies operation, a decision was taken that all pilots and passengers must wear a full military-style immersion suit. This practice continues today. Now undoubtedly, ditching into the North Sea exposes one to a hostile environment, especially in winter. But I do not envy today’s pilots having to spend 70 or 80 hours a month flying in such uncomfortable gear. There is a vast difference between the few hours a month flown by military pilots and their commercial counterparts. So not only do helicopter pilots have to contend with the noise and vibration in the cockpit and flicker of the rotor, but they now have to tolerate the sweat and discomfort of a rubber suit sealed at the neck. It is a far cry from Jock Cameron’s philosophy to put one’s resources into keeping the helicopter flying safely in the air rather than catering for the rare ditching. At the risk of being controversial one must ask the question as to whether today’s cockpit environment is conducive to alertness and a general “on-the-ball” feeling.

THE S61N FLIGHT SIMULATOR

Another BAH innovation to the world of helicopters was the decision to invest in a full motion flight simulator which would faithfully replicate the cockpit experience of the S61N. Redifusion Flight Simulation of Crawley, next to Gatwick Airport, were chosen to build this amazing machine. Captain Russ Williams, as Flight Technical Officer, was given the responsibility to liaise with Redifusion in order that the replication might be as realistic as possible and the final version would be able to simulate all likely emergency conditions encountered by the real aircraft. I believe it true to say that this was the first time that the design and build of a helicopter simulator had ever been attempted in the western world. The challenges were many, not least of which were the replication of all the various sources of vibration – two engines, main rotor gearbox, tail rotor gearbox, main rotor and tail rotor. Additionally, there were the unique instrumentation and failures on a twin-engined helicopter. The result was stunning. The cockpit environment was strikingly similar to the real aircraft. The one limitation was the visual aspect in that only two screens were provided, in place of the windscreens in front of each pilot, but with no side screens. This was not a problem for instrument flight but presented a challenge when attempting simulated visual flight.

The simulator was installed in a special new building at the BAH base in Aberdeen. Captain Pete Bramley was appointed Chief Trainer. The simulator totally revolutionised training. Previously, training had been the poor relation and had to be fitted between commercial requirements. Often a training detail had to be cancelled at short notice. This often created problems as the 6 monthly checks, including instrument rating checks, had to be completed or pilots would lose their currency with consequent disruption to the crewing roster. With the arrival of the simulator training became stable, but the greatest benefit was the more sophisticated training now available because of this amazing machine. For the first time ever we could pull the T-handles during simulated engine fires. On one occasion Bill Flynn and I were under training when the trainer gave us what is called a “flex-drive shaft failure”. This is a very confusing emergency in which engine and torque needles swing wildly backwards and forwards over the dials and it takes careful analysis to determine what has gone wrong and the correct action to take. There is no aeroplane equivalent. That day, on the simulator, the trainer was able to freeze the motion, viz. the simulator jacks cease to move and simulated progress over the ground is halted. We were able, at our leisure, to carry out the diagnosis and take the necessary actions to bring the situation under control. It was a sea-change in the modus operandi of helicopter training.

Later, BAH went on the purchase a Boeing 234 simulator with wrap-around visual screens.

As an amusing aside, just prior to the commissioning of the S61N simulator, a discussion regarding its availability to Bristow Helicopters took place at the monthly management meeting in the Beehive. Jock Cameron chaired these meetings at which all the base managers were present. There was a general sentiment that Bristow Helicopters should not be given the use of the simulator. I asked why we should object to taking money off our competitors provided the price was right. Jock’s eyes gleamed and the decision was immediately made to sell time to Bristow’s! Later, not only Bristow’s but also BCALH leased time.

TRANSCRIPT OF ARTICLE IN BEA NEWS, FRIDAY, 19 JANUARY 1968

BEA HELICOPTER IN BIG AIRLIFT AT SEA

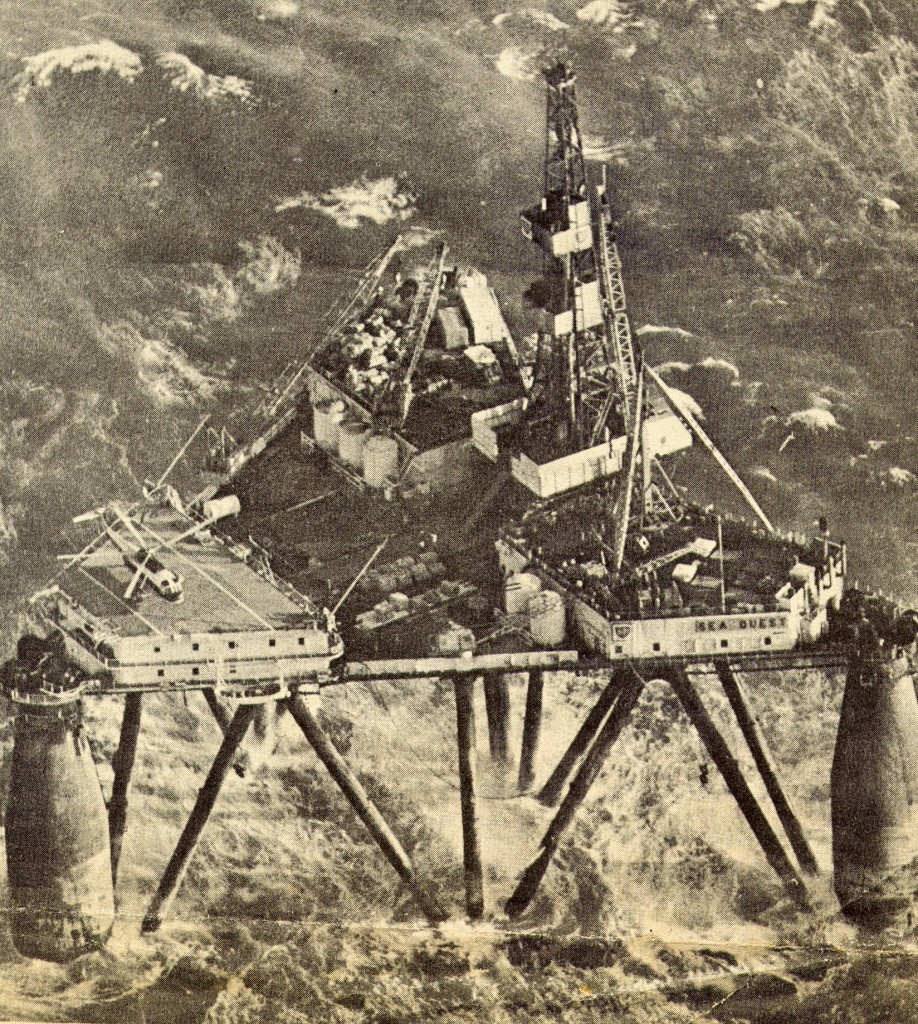

It was “interesting.” That was how a BEA helicopter pilot modestly described the airlift of 22 men from the giant oil rig “Sea Quest” as it dragged its anchors in a 50-knot gale. But Captain Mike Evans, who was co-pilot at the time, went on to praise the “skilful airmanship” of Captain Russell Williams, who was in command of Sikorsky S61N helicopter “Foxtrot Mike”. Having no passengers on board made it even more tricky for Capt. Williams to nurse the big helicopter on to the none-too- steady landing pad of the drifting rig out in the North Sea. The 22 men, most of them drillers, quickly filed aboard and the aircraft was airborne again within three minutes. Third crew-man was Cabin Attendant Roy Dimbleby. Capt. Evans emphasised, however, that apart from the weather conditions it was “more or less” a routine air lift, not an urgent rescue operation. He said that British Petroleum, owners of the rig, asked BEA to take the men off as a precaution because, since there was no drilling being done, they were not needed on board. The semi-submersible rig, which BP officials stressed this week was designed to withstand gales, was drifting at about two miles an hour when the BEA helicopter men found it with the help of the rig’s beacon.

SPEED The aircraft had flown 110 miles from Beccles, near Lowestoft, and Capt. Evans said that when they reached the rig they were just within the operating range to pick up maximum payload. Wind speed at the scene was 50 to 60 knots, but he added that the rig’s design stopped it pitching greatly. Another 16 of the oil men were lifted from the rig in a smaller helicopter, leaving 19 key men on board as tugs ploughed through the North Sea to the Sea Quest’s aid. Photo below: Not far above an angry North Sea, BEA helicopter “Foxtrot mike” lifts off from the landing pad of the drilling rig “Sea Quest”, taking 22 men to safety – just in case. This dramatic aerial picture was taken by Daily Express cameraman George Birch.

SEARCH & RESCUE

BAH was awarded a Search & Rescue contract. The first of its kind given by the UK Government to a civilian company. This contract was driven by the late Captain Tom Price and in his safe hands went from strength to strength. The following newspaper article sums up what was achieved.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

TRANSCRIPT OF NEWSPAPER ARTICLE (THE ABERDEEN PRESS & JOURNAL circa end of 1983 or early 1984)

YESTERDAY marked the 10th anniversary of the epic rescue of the crew of the trawler Navena—a four- and-a-half-hour drama in which a British Airways Helicopters S61N winched 12 men from the deck of the vessel, aground on the rocks off the island of Copinsay. That was BAH s first major rescue in their 12-year search-and- rescue service, operated in conjunction with the coastguards. On November 30 that contract came to an end, and today FRED PARK looks back over some of the dramas—and lighter moments—of SAR.

AT 1106 hours on November 6, 1971, a British Airways Helicopters S61N took off from Aberdeen on the first sortie of a two-year “trial” contract awarded by the Department of Trade to provide a search-and-rescue service for the northern North Sea. At the controls were Captains Ashpole and Price, with crewmen Terry Chappell, Ken Jacobs and Gordon Strathaim on board. The mission—to assist the British freighter Amberleigh, which had lost steering in a Force 8 gale. When the helicopter arrived at the scene, the crew had succeeded in regaining steering on the Amberleigh and “no further assistance was required”.

According to the aircraft’s log, the S6IN was back at Dyce at 1241: the three crewmen had had a dry run for their first mission, but within one month the SAR service was called out to lift a severely injured seaman from the Danish trawler Viking Bank, this time with Dr David Proctor from Aberdeen’s casualty unit on board. Crewmen on that occasion were Ken Jacobs, Gordon Strathaim and, making his “debut”, Ted Clarke, with Captains Price and Hooper at the controls. That mission of 3hr. 20min. duration was a taste of the real thing.

When the last contract ended, on December 31, 1982, BAH had flown more than 130 missions, some more dramatic than others, and their crewmen had amassed an enviable collection of Rescue Shields, Queen’s Commendations for Valiant Service in the Air, a Queen’s Gallantry Medal and other national and international awards. Throughout 1983, they have operated extensions of the contract until last month.

But the story of search and rescue goes back to the early 1970s, when Danish, Norwegian and American helicopters had been called in to rescue crewmen on two stricken vessels. At that time there was no British rescue capability using long-range helicopters, but eventually, and after pressure in the Commons, the Coastguard service was given that vital air support.

The first contract went to British Airways Helicopters, operating from the former RAF station at the west side of Aberdeen Airport. Today, only two of the original crewmen are still with BAH, cabin services superintendent Terry Chappell and cabin services supervisor Pete Garland.

With one exception, the crewmen stationed at Sumburgh, to where operations were transferred in 1979, have now transferred to Aberdeen, where they will work on the BV 234s, and will be involved in the development of a new, heavy-lift service using the Boeings.

Coming back to the 1970s, and to the early hours of December 6, when the British fishing vessel Navena ran aground on a reef 600 yards horn the rocks on Copinsay. At 0810 hours an S61N was scrambled from Aberdeen with Captains Evans and Price at the controls. Terry Chappell and Ted Clarke were the crewmen on what was to be the unit’s first major search-and-rescue operation.

On the rocks off Copinsay the trawler Navena was badly holed and sinking. On board, a crew of 12 with the ship being battered by Force 10 winds. The weather was so bad that Kirkwall lifeboat took four attempts—and 50 minutes—to get out from port. Skipper Jim Clark was last to leave the ship on that fateful December morning, when the helicopter was the only chance left for him and his crew. For that rescue, the crew received the Department of Trade’s Rescue Shield for the most outstanding rescue of the year and a Queen’s Commendation.

For a brief spell it was back to routine “casevac” and “medevac” sorties and land- and-sea searches, plus the never-ending routine of training exercises. By the time of the Navena, the team of winchmen and pilots had formed a rapport that made verbal communications almost unnecessary. Training had made sure that the teams could really work together: the Navena showed just what that teamwork could achieve, under the worst possible conditions in the North Sea.

The New Year celebrations to herald 1974 were “out” for the duty SAR crews, who, only four days into 1974, were scrambled to assist the Polish trawler Nurzec, aground at Murcar, north of Aberdeen. Pete Garland and Ken Jacobs were the crewmen who had to attempt the dangerous task of winching up survivors from the storm-tossed seas tossed seas and the deck of the vessel. They rescued four men from the trawler, in pitch darkness and in the teeth of a Force 10 gale; they recovered three bodies from the beach before having to return to base. Next day, they pulled the last four men to safety from the trawler.

But it was from Sumburgh, not Aberdeen, that one of the most dramatic rescues was to be carried out, again in the early days of December—again in Force 10 gales. On December 9,1977, an S61N was scrambled from Sumburgh, with Captains Bain and Bosanquet and crewman Brian Johnstone, to go to the aid of the fishing vessel Elinor Viking, foundering on the rocks off the Skerries. After a search hampered by darkness and foul weather, the helicopter located the boat and lifted four of the crew on board. Below, the lifeboat could not reach the Elinor Viking, which was rapidly breaking up, and the helicopter made a second and successful attempt to rescue the four remaining crewmen on the boat. That rescue earned no fewer than nine top awards, including two Queen’s Gallantry Medals and the US Coast Guard Captain Kessler Award.

In 1978, it was decided to position the search-and-rescue service at Sumburgh, the first sortie from there being flown on June 19, 1979. But the last rescue performed from Aberdeen also lived up to the spectacular tradition of SAR. On December 16, crewmen Jacobs and Garland, with pilots Buckley and Ingledew, went to the aid of a crewman on the bulk oil tanker Dinos M. The seaman had been overcome by fumes and BAH winchman Pete Garland was lowered to the deck of the tanker. The helicopter returned to base and Pete Garland made three attempts to rescue the seaman and bring him up on deck. Using breathing apparatus for an hour and a quarter, Pete Garland finally got the seaman topside, but the man was dead. For his part in this rescue. Garland received a Royal Humane Society award.

The annals of SAR are packed with examples of skill and outstanding courage, but the service also had its lighter moments, many of which are still fresh in the minds of the crews, and are oft-quoted in after-dinner speeches. Common to many of these anecdotes is a dummy which the BBC had presented to the SAR unit. The dummy was used regularly in exercises, and for more light-hearted pursuits – on occasion. “Fred”, as British Airways Helicopters had christened the dummy, was found lurking in some strange and often out-of- bounds places. He was also used as a “victim” in rescue exercises. On one occasion a TV crew were on location, filming with BAH, the script calling for a young female personality of the time to be winched off the deck of a (wrecked) trawler in a stretcher. The Sheriffmuir, off Balmedie, was the location, but the star of the show declined, I am told, to be winched up. So Fred was strapped in, and lowered from the helicopter to the set. Cameras on the beach were whirring—when Fred fell out! Vital to the story is the fact that the camera crew did not know of the last-minute substitution, of the dressing of Fred in the star’s apparel. Their horror at the sight of the rapidly-descending figure was compounded tenfold when a BAH crewman wandered up to the body—now spread-eagled on the sand—and delivered a hefty kick which decapitated the victim. That story I heard so often that it must be true, but some of the feats attributed to Fred (who also transferred to Sumburgh) defy belief.

The last wet winching “rescue” carried out by BAH was in support of “The Press and Journal” Cavitron appeal, when I was winched from the sea off Bressay — and, although I knew I was going to be rescued, I was more than a little relieved to see the winchman descending, with the rescue strap held out. I now know that even an S61N with the main door removed to accommodate the winchgear is a warm and welcome place compared with the sea. In 12 years that relief has been felt by hundreds of men and women whom British Airways have rescued, but the last word comes from Mr David Mitchell, Parliamentary Under Secretary at the Department of Transport, in a letter dated November 24, 1983, to BAH’s managing director, Mr M. C. Ginn. That letter expressed “the Government’s appreciation of 12 years of service, bravery and courage—exceptional airmanship”. It concluded: “You and your staff involved in that contract can take justifiable pride in a job well done—and appreciated.” That, on behalf of those hundreds rescued, says it all.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

TRANSCRIPT OF ARTICLE IN THE ABERDEEN EVENING EXPRESS – 5 JANUARY 1972

THE BUSIEST BASE IN BRITAIN —THAT’S DYCE’S HELICOPTER FUTURE

Helicopters have become a familiar sight in the skies over Aberdeen as they ferry men and goods to and from the North Sea oil rigs. Now BEA are to make Dyce their helicopter HQ for Britain. INNES STEPHEN finds out what this will mean to Aberdeen’s airport.

IN THE NEXT year Aberdeen will become the busiest helicopter base in Britain with perhaps as many as eight of the giant Sikorsky S61′s in operation at Dyce.

For progress, both technological and economic, is now strongly represented at Aberdeen Airport, and, in terms of helicopter value, there is a bigger investment here than anywhere else in Britain. BEA are to spend around £200,000 in moving their engineering and administrative headquarters to Aberdeen, because their biggest future prospects lie in this region. Bristow have spent £20,000 in building a hangar with offices, stores and engineering base. Both companies expect that their future at Aberdeen could extend to 25 years or more. And the helicopter operations complex is set to build up swiftly to become the most sophisticated in Britain within three years.

s a scene that is repeated noisily several times a day as BEA and Bristow get down to the grind of ferrying men and freight to the North Sea oil rigs. s a regular occurrence to watch the ungainly helicopters fly out and in.

The men who fly them are no less remarkable than their machines. Of course, there has always been an aura of glamour around “those magnificent men and their flying machines.” ‘ If the aura around these pilots shines a little brighter it is probably because they are a lot closer to the original pioneering breed about whom the phrase was coined than are the men who fly the regular airways. They will be the first to deny that their job is anything other than ordinary. Such modesty is only to be expected. IN FACT THEIRS IS PROBABLY THE MOST CHALLENGING ROUTINE FLYING WORK IN THE COUNTRY.

They have got to keep the links with the oil rigs open; they have got to land on tiny platforms which are almost indiscernible in the midst of the heaving sea; they have got to fly further from the safety of land than any other helicopter pilots in Britain. And the BEA pilots have willingly taken on the job of long-range rescue, which, almost inevitably, means flying in the foulest of conditions. These hazards and tests of skill are shrugged aside. Captain Doug Pritchard, BEA Helicopters’ commercial manager, commented: “I wouldn’t think it is any more hazardous than flying anywhere else.” “Great care has to be exercised in landing on the rig platforms, and certainly the Scottish weather conditions tax people’s skill because you get gales, fog, snow and icing in full measure.” “You don’t just get a little wind, you get a roaring gale. You don’t just get frog, you get this Scottish Haar which reduces visibility to 50 yards.” “YOU CAN SEE THE SUN SHINING ON A RIG AND TEN MINUTES LATER IT IS COVERED WITH CLOUD.” “This is why we exercise a rule that every aircraft must fly with sufficient fuel to go out and back again.” “I think you could say that flying does require the exercise of great skill for these reasons.”

As commercial manager, Captain Pritchard must look at future as well as present activities. He expects a high level of activity in the oil business for at least seven years and a good measure of business for 30 years. As the pressure of oil business falls off and finds a level, the company anticipate that commercial scheduled services to the Highlands and Islands based on Aberdeen could dovetail in. The target for introducing a new, bigger and far more economic Sikorsky helicopter is 1975, and BEA have been looking at this with Scottish services in mind, so the decision to establish their main administrative and maintenance base in Aberdeen was a logical one. Initially they will build a hangar for two aircraft, but they hope to get other hangars at the airport for storage of the remainder of their fleet.

Apart from that, there will be accommodation for administration and engineering operations and passenger handling in a separate block. BEA will buy one and perhaps two more helicopters in the present financial year. Estimates suggest that there will be 25 rigs in the Scottish sector of the North Sea in 1974. That would mean that BEA would need something like 10 helicopters based at Aberdeen and Sumburgh. Even when the oil search moves around to the west coast and some of the helicopters are moved to a base there, they will continue to come to Aberdeen for servicing. To deal with an operation of this sort, about 70 or 80 staff will be employed. At present there are 18 pilots based on Aberdeen. This will increase to about 25 this year, and more after that.

Bristow Helicopters, who have one machine at Aberdeen at present, will be getting another very soon and possibly a third later this year, according to Captain Mike Wood. They will also be starting a base at Sumburgh. Their skilled maintenance staff will number about six next year, with four to six local labourers. There will be at least 10 pilots in Aberdeen. Captain Wood could not predict how their involvement in Aberdeen would develop, but he was certain that the company would not have gone to the bother of building a hangar if they did not expect their operations to be long-term.

What difference have the helicopters made to Aberdeen Airport? Even though they are still in the early stages of development, the helicopter operations have put accommodation at a premium and have greatly increased the traffic in and out of the airport. In October, for example, there were 2620 aircraft movements. Of these 405 were scheduled services, 528 helicopters. 453 charters, 981 private, and 35 executive flights. So the helicopters account for more movements than the scheduled services of BEA and Air Anglia combined. Although they can carry only 20 or less passengers on every trip, the amount of people they transport every month is considerable. In September for example the BEA helicopters flew a total of 380 hours. They carried 1122 passengers out to rigs and 1090 back. Between rigs they carried 239 passengers, and they carried a total of 63,1201b of freight. This year there could be as many as 1200 people working out in the North Sea—about twice as many as in the busiest periods this year, and a lot more business for the helicopters.

RESCUE!

BEA HELICOPTERS have already been called out on actual North Sea rescues. Their first job, however, was a simple matter of dropping a man down to a ship which had an engine fault (writes INNES STEPHEN). If the past winter It anything to go by, Captain Tom Price, who is in charge of the search and rescue section, estimates that their help could be needed about nine times between now and April. Until the next call comes, the search and rescue section can only sit and wait, and train to be able to deal with any eventuality that may crop up.

The “Evening Express” was the first newspaper to fly with them on an exercise to see the problems they face and the way they tackle them. It was carried out in the calm of Aberdeen Bay under almost perfect conditions, with the Aberdeen University ship HMS Thornham acting as “target” and two members of the coastguard at observers. The helicopter came in crablike to hover at an angle over the stern. First one winchman went down, and the helicopter swerved sideways, up and away in a great circle. Back again and the man was hoisted slowly, steadily into the aircraft. Another circle and the process was repeated over again….and again….and again. In cockpit Captain Price’s hands rested lightly on the engine throttles, his concentration on the ship’s mast only a few feet away from the whirling rotor blades as we hovered. The helicopter would occasionally dip away from the few square feet of grey painted decking where the man was to be landed – otherwise everything was perfect once the forward movement of the boat and the quarter sideways and three quarter forward motion of the aircraft were synchronised. It was so simple and so precise. But after all Captain Price and most of the other BEA Helicopters’ pilots were trained in exactly this sort of work with the services. And with a well-practiced art the old skills return quickly.

Of course it will not always be so easy. A pitching, wallowing trawler and a howling gale driving rain or sleet before it is a different proposition entirely. Every type of vessel sets its own problems. The helicopter is two feet longer than the average seine-netter, and the winch-man would have to be landed in the bow, so the pilot has almost 70 feet of aircraft behind him that he doesn’t see. He is flying blind, relying entirely on the crewmen talking him into position. Or if a yacht is involved, the chances are he cannot come directly down because of the height of the mast and the restricted length of cable from the helicopter winch. Under these circumstances a rope will have to be lowered from the cable, and once it has been grabbed by those on board the helicopter will descend alongside so that the cable can be pulled on board.

The winchmen, too, are experts in their job after long service with the Navy or Air Force. In charge is Terry Chappell. He spent over two years on Shackletons at Kinloss and a further four years on helicopters at Valley in Anglesey, so that he has seen all aspects of airborne search and rescue. Like most of the BEA men he has now settled down in the North-east and is staying temporarily at Kemnay while a house is being built for his family at Inverurie. His colleague Ken Jacobs was stationed in the search and rescue section at RAF Leuchars for many years and he bought a house in nearby Anstruther. He has kept on his house in Fife and now has five hours driving every week between there and his “digs” in Aberdeen.

Not all the BEA staff took kindly to a posting to Aberdeen. One pilot commented: “I came here at the wrong end of a pistol.” But he smiled as he said it. And there are the usual comments from others about “the frozen north.” But generally speaking every-one is happy and settled. Captain Doug Pritchard described his feelings, which are probably fairly representative. “I was, in fact, fairly disturbed when I heard I was being posted to Aberdeen. “I have always lived in a line between the Wash and the Bristol Channel. “Quite frankly we nearly had a divorce the first week because we hared around trying to find n house. “Now I would rather be here than anywhere else In the UK. I think It Is an absolutely marvellous place. “I am living in Banchory and the people are exceptionally friendly and kind. “I have made more friends in four weeks here than I made in ten years in southern England. “In fact you will find this reaction from most people. Initially they think it is a terribly long way north. “For example a chap will say that it is terribly difficult to get to London. He probably lived about 20 miles away from London, but when you ask him when he was last there it was probably about five years ago” Happy they have to be, for they can only go where their work takes them. And for many years, for many helicopter pilots, that means the North-east and North of Scotland.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Transcript of article from the Press & Journal – Monday November 16 1970

Distress drama in stormy North Sea

SUNK HELICOPTER TRIO RESCUED

CAPT. David Creamer (centre), who was piloting the helicopter which sank in the North Sea, points out the location on a map to two of his BEA colleagues, Capt. Robert Simpson (left) and Capt. David Eastwood (right).

TWO BEA pilots and a civilian passenger were rescued by a Swedish cargo ship after their helicopter ditched in the North Sea about 50 miles off Aberdeen yesterday.

Captain David Creamer, who brought down the long-range helicopter in a heavy sea whipped up by gale-force winds, had to swim about 10 yards to a rubber dinghy after the aircraft rolled over while he was salvaging equipment.

A former Navy jet fighter pilot, and helicopter test pilot, Captain Creamer, his co-pilot, Captain Keith Gregson, and the civilian, Mr Alan Mendes, were on a routine flight to the Staflo oil rig when the helicopter developed a malfunction.

Looking fit and apparently none the worse for his ordeal. Captain Creamer last night described how he and Captain Gregson brought down the stricken helicopter, not knowing if anyone had heard their Mayday calls, and of their stroke of luck in being picked up within 90 minutes by the Montrose-bound Gripan.

Captain Creamer explained that, when the helicopter developed a main gearbox lubrication supply failure, he had to put her down in the sea in winds of up to 35 m.p.h. and 15ft. high waves.

Ten minutes later the helicopter sank.

A married man with three children, Captain Creamer was transferring equipment to the dinghy when the helicopter suddenly rolled over. He said: “I left it a bit late, but there was no danger. The aircraft rolled so that the door was facing up and it was easy to get out. It floated for about five minutes before rolling over again and sinking.”

As they shivered in the pitching dinghy, he said, they were anxious about having had no replies to their distress calls

But after spotting the lights of the Gripan they sent up a distress rocket and flares at five-minute intervals. The Gripan, they learned later, saw the first signal and they were picked up shortly afterwards.

Captain Creamer praised Mr Mendes, a Shell BP employee, for remaining calm in the emergency.

He said: “Mr Mendes put up a good show. He didn’t lose his head and did exactly as we asked him to do.”

HEAD KNOCK

Captain Gregson was last night recovering at his home, Switha, South Headlands Crescent, Newtonhill, from a knock on the head he received while climbing aboard the Gripan.

Captain David Eastwood, BEA helicopters operations manager at Dyce, said: “Captain Creamer did a most remarkable job on this. I think the crew were really excellent. You don’t land at night in a rough sea for pleasure. It’s a particularly difficult thing to do.”

He added that BEA helicopters engineering staff would make special intensive checks on all aircraft before further flights.

He did not think there was much chance of recovering the £400,000 helicopter.

As the Gripan could not enter Montrose Harbour until high tide at 2 p.m. yesterday, she was met by the Montrose pilot boat.

The three men were transferred to it and Dr.A. E. Mowatt gave them a medical inspection.

Waiting at the harbour side was an ambulance, which took the three men to Dr Mowatt’s home at 2 Warrack Terrace.

ADMIRATION

After a bath, a change of clothes and a bite to eat they were met by BEA official, Captain Simpson, who arrived in a taxi from Aberdeen.

Earlier Mr Mendes was taken back to Aberdeen by Shell BP officials.

As Captain Simpson left the home of Dr Mowatt, he stated: “There will obviously be an inquiry, but I have nothing but the greatest admiration for my men and the civilian.”

Five hours after the men were landed the Gripan arrived at the harbour on the high tide.

Captain Bernt Abrahams-son (33) from Goienburg, said that he had been making a normal run to Montrose with a general cargo of timber and paper.

“On Sunday morning my mate on the .bridge told me to look out the window,” stated Captain Abrahamsson. “I saw a red light — as if somebody was in distress. From the bridge I saw a white light and the occasional flare, about four nautical miles away. This was about 2 a.m.”

“By 2.25 a.m. we had thrown a line over the side and taken the men aboard. They were all physically all right.”

“The sea was not calm, but neither was it rough. I would say it was about five to six force winds.”

Montrose pilot boat with the doctor on board met the Gripan at 8.15 a.m.

The helicopter, a Sikorsky S61, is one of two used by BEA on regular ferry flights between the mainland and the oil rigs.

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Transcript of article – unknown newspaper – probably Press & Journal

HELICOPTER IN INJURED BOY DRAMA

AN ACCIDENT involving a 17-year-old boy on board a Scottish trawler sent a BEA helicopter 130 miles out over the North Sea late on Tuesday.

The boy, reported to be the son of the skipper of the Aberdeen trawler Onam, was severely injured in an accident with a winch. The trawler sent out a Mayday call and was advised by Coastguards to head for the Shell rig Staflo, nearest to the trawler but, at 130 miles off Aberdeen, the furthest of the rigs serviced from the BEA helicopter base at Dyce.

A BEA Sikorsky S61N helicopter from Dyce was in turn ordered out to the rig to await the trawler.

The helicopter, with Captain Don Huggett, 36, in command, took off at 2123.

The trawler arrived at the rig at 0105 Wednesday The boy was flown to Dyce, where an ambulance was waiting to take him to hospital.

LIFEBOAT

Aberdeen lifeboat was launched during the rescue in case fog in the area of the rig prevented the helicopter from taking off again.

The other members of the helicopter crew were Captain Bill Flynn and Engineer Dennis Webb. The rescue came at the end of a day during which bad weather had stopped all routine flying from Dyce, including rig crew relief trips.

As well as the helicopter crew, it meant a late night for the ground support team—fitter Doug Shand, Charlie Patterson and Peter Gibson, who was co-ordinating the rescue—at Dyce. BEA Edinburgh Station Assistant Sid Ball also stayed on duty until the helicopter returned to base at 0400 in case a diversion became necessary.

Captain Hugget is a holder of the Air Force Cross, awarded for a helicopter rescue he undertook while in the RAF. The citation said that despite extreme snow and ice conditions, Captain Huggett carried on with the rescue and in fact continued to operate beyond the theoretical endurance of his machine.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

You may not remember me but I was a Sikorsky S61N pilot with Bristows on detachment to LSI in 1972. I returned in 1973, having married a Scalloway lass and lived briefly in the Bristow married patch.

I find your articles and reminiscences absolutely fascinating! I had started in ABZ in 1971 , having been told by BHL management I was going to the Far East, it transpired that this was to be the Far East of Scotland!

Mike Wood was my first ‘proper’ Chief Pilot after the initial start up with Alastair Gordon and Ken Bradley. Mike sadly died just recently having been ill for a few years. Ken Bradley is still alive and well according to his daughter.

One question…..wasn’t the S61 lost in 1970 G-ASNM? I thought the crew was Keith Gregson and Dave Creamer, not Sandy Sanders?

So many names here and so many memories. I thank you again for this website.

Yours Aye

Dave Clare

Hi Dave – Great to hear from you after all these years. I hope you are in good health. It is sad to learn that Mike Wood, like so many others, has now experienced “life’s greatest adventure” – hence the need to record our little contribution to aviation history before it is lost forever.

You are absolutely correct. It was Dave Creamer and Keith Gregson and the aircraft was G-ASNM. It could not have been G-ATFM as my logbook records me flying it post the incident. I have corrected the entry on the website and will also include a transcript from the Aberdeen Press & Journal of 16 November 1970 which gives further details. Thanks for the correction. I would appreciate any other comments or contributions which would be accredited to you by name.

My best wishes to you and yours

Bill

Hi! I am the son of Brian Johnstone who participated in the Elinor Viking rescue. It was a joy to find the article on him on your site! Sadly he passed away on June 6th 2000. Please let me know if you happen to come across anymore articles with my father in them. Best regards from Martin Johnstone.

Dear Martin – I am very pleased that you saw the article on my blog but sad to learn of the passing of another colleague – an all to frequent occurrence these days. I have no more articles at present but perhaps other correspondents may have. Best wishes. Bill Ashpole

Fascinating stories about early days of North Sea. I worked on Staflo in 1974.

I preferred Helikopter Service A/S, who flew from the former military airfield at Forus, Norway. I flew with them in 1975-76 and was impressed by the insulation they had on the inside of the fuselage.

Hi Gordon – Thanks for your comment. I well remember Staflo as BAH had a contract for many years with Shell and Staflo was their rig. Our North Sea S61N’s were quite noisy in the cabin and it was just as well that flights were relatively of short duration. I hope you have good memories of your travel to work with Helicopter Services A/S and your work in the oil fields generally. Best regards Bill Ashpole

Very interesting to read about these early years in the North Sea, it must have been exciting times for all…. I wanted to let you know my grandfather Captain Pete Bramley passed away peacefully on Thursday 10th November 2022, aged 93.

I’d be delighted to hear of any more stories anyone can share, Capt Pete always spoke fondly of his time in the RAF & many years of commercial flying….