Caution on copyright should you wish to use photographs and diagrams from my website. I have included attribution wherever known and attempted to seek permissions from authors/owners of copyright who could be still found. This was not possible in all cases as the source of the photo was unknown or no longer in existence.

Why Shetland?

With the success of oil exploration and production going well off the coast of Aberdeen, the search moved progressively northwards. This is not to say there had been no previous exploration to the north but towards the end of the 60’s the search off Shetland began in earnest spurred, undoubtedly, by the fact that the Norwegian oil industry had found oil half way between southern Norway and the Shetland Isles. Helicopter pilots and engineers of both BAH and then Bristows soon found themselves spending more and more weeks at a time away from their families and staying in the Sumburgh Hotel or even the Lerwick Hotel, neither of which were too appealing.

BAH were first to arrive and shared half of a former wartime hangar with Loganair who operated a TriLander aircraft piloted by Captain Alan Whitfield. Harvey Pole was the Station Engineer for BAH and he and his team of stalwarts performed miracles in keeping the initial S61N flying in spite of the cold, the wet and the wind and later as the fleet of aircraft grew until Sumburgh was the biggest base in the company. The weather statistics for Shetland were formidable. On over half the days of each year one could expect gusts of over 35 mph but worse, hurricane force winds of over 100 mph could be expected on three or four occasions per year! Cognisant of the increasing separations from my wife and three children, I made a decision. I visited Jock Cameron at Gatwick and offered to be Manager for the Shetland operation. He almost bit my arm off and I found myself selling up and moving northwards. My decision had a more altruistic side: BAH were recruiting new pilots at a great pace for the expansion in Shetland and it seemed rather inappropriate not to have someone with S61N experience permanently present on the base. Jock fully understood the point.

As mentioned earlier, selling my house on the south side of Aberdeen was easy. Finding somewhere to live in Shetland was something else. For the first two months we hired a caravan situated some five miles north of Sumburgh airport. The Shetland Isles consist of hundreds of islands with the largest, known as Mainland, some 70 miles in length in an inverted “L” shape. Sumburgh is situated at the lowest extremity of Mainland with Lerwick, the capital and only town, situated some 30 miles to the north. We then moved out of the caravan into a small croft next to a dairy – a far cry from the accommodation to which we had been used.

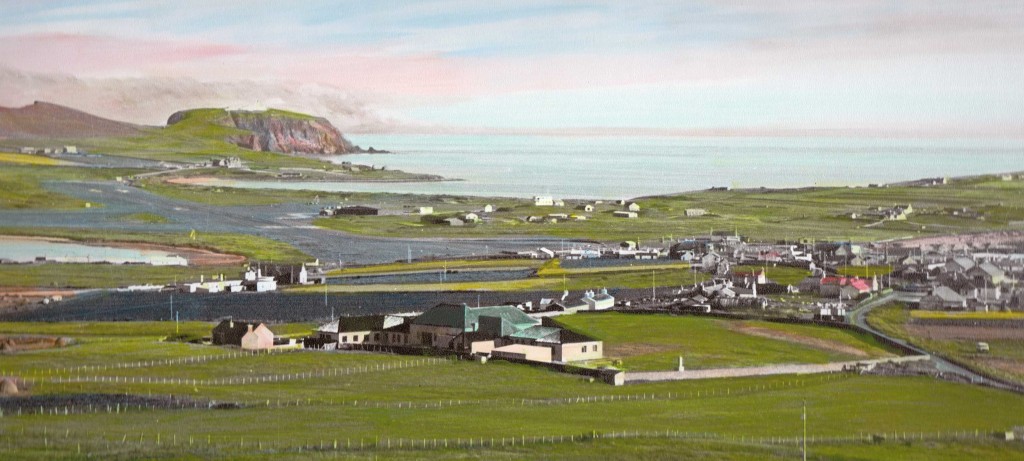

Sumburgh airport – 1969 – photo by J A Manson. Sumburgh Head in the far distance; the two runways clearly visible with the one black hangar; the white control tower to the right of the hangar; the Norwegian wooden housing, my own house and the company housing were built on the headland to the right of the photo.

Shetland was and is a very rural community with wild picturesque countryside none of which is more than a very short distance from the sea. Huge precipitous cliffs and rocky headlands abound everywhere. The islands are barren of trees except for one small area. It was on this scene that we arrived with “sophisticated” southerners – pilots, engineers and operations staff – who were used to a very different way of life and living conditions. BAH had to build not only hangarage but complete housing estates to accommodate the staff and their families. All this would take time – lots of time! In the meantime everyone had to manage as best as they could!

Initial relief for the staff and families was provided by the local council. They purchased and installed a dozen Norwegian timber houses and built an estate just to the south of the airfield. These three bedroom houses had insulation the like of which I have never seen before or since. They were very warm and cheap to heat and had the added advantage of being in walking distance of the airfield. I say walking distance but in winter, exposed to a 45 mph wind, one gains a new perspective on the expression “the wind cuts through you”!

Construction of hangars commenced but would take time. In the meantime the helicopters would have to remain in the open – and open to the elements! We experienced all kinds of unserviceability which could be directly attributed to the inclement weather, especially the wind and rain. Harvey and his team battled to keep them serviceable and to their great credit we managed to provide a reliable service to our oil company customers who learnt to give and take in the allocation of aircraft and not insist on their own particular airframes.

There was one aspect of the weather that was especially stressful for me as Manager. Extreme gusts of wind can cause an effect known as “blade sailing”. This is when stationary rotor blades with their leading edges facing the direction of the wind are subject to a speed of airflow which creates sufficient aerodynamic lift that they rise vertically. They can, in fact, rise up and then crash down subjecting the rotor head to extreme forces and actually bend the rotor blades. This was demonstrated to particular effect one day when there was a coming and going of helicopters and a Royal Navy Sea King, the military version of the S61N, was sitting with rotors stationary in front of the airport terminal building. A huge gust hit the airport; the blades of the Sea King were severely kinked and had to be replaced with the help of our engineers. My dilemma with this aspect of helicopter operation was to decide each afternoon whether we should scramble our fleet, numbering as many as six S61N aircraft, to Wick airfield on the Scottish mainland where there was hangarage. Fortunately, this contingency action was only required on a relatively small number of occasions before the new hangar became usable.

Although we initially had a couple of offices in the old terminal building, by the grace of Jim Burgess, the BA station manager, our growth soon required an alternative solution. I began ordering Portakabins until we had a “Portakabin Empire” housing Operations, Pilot’s Crew Room, Engineers, etc. and even a very large one named “The Portapub” which was for social activities. None of this was ideal but it enabled us to live and operate as the base grew and grew. When I left Shetland, after spending three years as Manager and Chief Pilot, the Aberdeen base had shrunk and the Sumburgh operation was by far the busiest base in the Company. In the height of its development, it had over a dozen S61N aircraft operated by BAH and, in addition, the Bristow fleet.

The operational procedure on all flights was to give a position report every 10 minutes. This was transmitted by VHF radio (Very High Frequency) when relatively close to Shetland but on HF radio (High Frequency) when further out. (VHF radio transmissions are limited to more or less to line-of-sight; HF radio waves have the ability to “bend” around the curvature of the Earth and so permit longer range communication albeit at the cost of reliability and clarity). BAH and Bristow’s each had an operations room for monitoring transmissions. With the increase in helicopter traffic it became apparent that there was an ever growing danger of a mid-air collision between aircraft. I met with Captain Terry Wolfe-Milne, the Canadian Manager of Bristow’s, Shetland, to discuss the problem and we decided that some form of air corridor system and joint air traffic control was necessary if disaster was to be avoided. My Assistant Manager, Captain Dave Clem, represented BAH at the subsequent nuts-and bolts meeting where the system was thrashed out. It needs to be said that National Air Traffic Services (NATS) had been approached but they declined to assist in any way. So a system of corridors was established based radially on Sumburgh airport and extending to the main centres of rigs and platforms. Aircraft were assigned altitudes inbound and outbound and position reports were passed to the BAH operations room in the new hangar. We had established the first ever helicopter air traffic control system. This system was developed as years passed until eventually NATS took over the management and day to day control.

ANOTHER ENGINE FAILURE

As explained in the section on Gatwick, the S61 has insufficient power, even at its 2.5 minutes 1350 shaft horsepower rating, to hover on one engine if the aircraft has much of a payload. Thus landings and take-offs to and from oil rig helicopter platforms always involved a few seconds during which disaster could strike should one engine fail. Good technique could minimise the risk. On 23 January 1975, I was landing G-AYOY on the Zapata Ugland with co-pilot Dave Owen. Just as I lowered the lever we heard the unmistakable sound of a jet turbine stalling. Fortunately, the landing was almost complete so all that remained was to shut down and check the cause. Inspection revealed that the rod which changes the pitch on the first four stages of stator vanes on the compressor of one of the engines had sheared. The resulting starvation of air to the compressor had caused the stall.

I sought and obtained permission to fly the empty aircraft back to Sumburgh on one engine. There was a wind of 20 knots or more over the helideck so we took off and, from a higher than normal hover, transited into forward flight. We had never practiced such a manoeuvre, even in the simulator, and it felt very strange. Captain Terry Wolfe-Milne, Bristow’s manager in Shetland, was flying nearby at the time and very courteously flew alongside to cover our return to Sumburgh. Although I had flown hundreds of hours over water, including the heavily shark-infested water of the Persian Gulf, in single-engine helicopters, piloting a twin-engine helicopter on only one engine made me very apprehensive throughout the flight – bizarre!

We returned safely to Sumburgh having saved the company a great deal of money and the engineers one enormous headache. We had also freed up the helideck for normal use.

Flying in “extreme” weather conditions

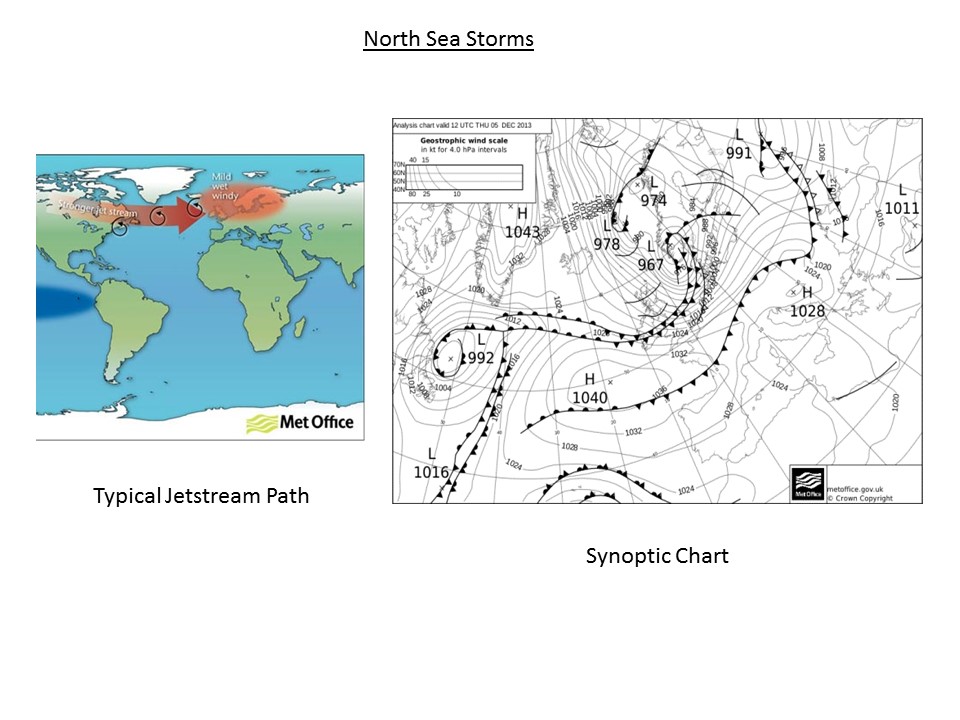

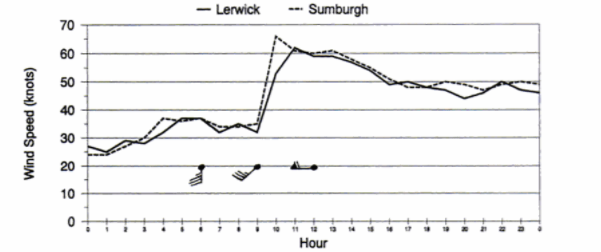

The Shetland Isles experiences extreme weather conditions. I read that the record mean wind speed was recorded at the Muckle Flugga lighthouse (the north end of the Isles) on the island of Unst at 73 knots (89 mph) with unofficial record gusts of over 150 knots/173 mph. The maximum reading of the wind speed indicator was 150 knots hence the record was unofficial. Shortly after, the indicator was destroyed by a severe gust sometime around 3 a.m. These speeds were, of course, recorded at ground level. Wind speeds at higher altitudes would be greater. Winds up to 100 mph battered the United Kingdom and Norway in Mid February 1974, killing 19.

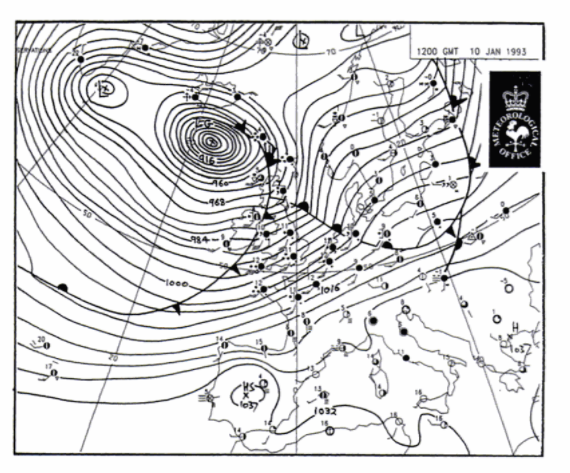

THIS SYNOPTIC CHART DEPICTS VIVIDLY THE TYPE OF BAROMETRIC SITUATION WHICH PRODUCES EXTREME WINDS. (THIS ACTUAL CHART POST-DATES MY TIME THERE BUT EQUIVALENT OR WORSE ARE TYPICAL FOR ANY YEAR)

Flying in winds of 40 or 50 knots is the norm in this region but occasionally there is a requirement to test the mettle of both aircrew and aircraft. The most extreme conditions I have ever experienced were, if memory and logbook serve me right, in January 1974. The Transocean III had been on station on the northern edge of a group of rigs almost halfway between Shetland and Norway. Between 29 December 1973 and 1 January 1974 the rig had experienced progressive structural damage due to storm conditions. The crew had previously been evacuated and the rig began to break up. There was a distinct danger that debris from the rig, such as the massive legs, would drift towards other rigs in the area. We were on standby at Sumburgh with three aircraft and crews waiting for the word from the oil company concerned, Mobil North Sea. The plan was to lift the crews from rigs in harm’s way and move them to other rigs. We received the order to commence the rescue operation!

That night the whole region was subject to a very deep meteorological depression with surface wind speeds of over 80 mph. We were faced with two immediate challenges. The first was one of navigation. The S61N on the North Sea was operated at a cruising airspeed of 110 knots. With a tailwind of 80 knots we would have a ground (or speed over the sea) of 190 knots – we would get to the rig in record time. But when returning to Sumburgh we would have a ground speed of 30 knots and would run out of fuel long before landfall! The answer was to carry out the transfers at the rigs, refuel at a rig, and then continue on to Stavanger in Norway and wait until the winds abated. The second was the blade sailing phenomenon referred to earlier in this section – the risk that when starting the rotor, a huge gust of wind would lift the advancing blade then leave it to crash down on the fuselage near the tail. We elected to start up in the lee of the hangar thus protected from the worst of the wind. This worked and we departed for the rigs.

Flying in such strong winds was rough but a helicopter has high wing loading (the ratio of all up weight to wing or rotor blade area) and so is not the handful one might imagine. We sped across the sea, with wave heights of perhaps 50 feet, in the knowledge that a ditching would almost certainly not be survivable in the S61N which would roll over in swells over six feet.

Landing on the rig’s helicopter platforms in the dark required some nifty handling of the controls but in such a wind strength we had plenty of power to spare. Although we had landed into wind in the lee of the rig superstructure, I was amazed to see the needle of the airspeed indicator vibrating at 82 knots! Sitting firmly on the large gauge rope netting, which is to be found on all rig heli-decks to reduce the possibility of sliding around, we gave the thumbs up for the rig crew to approach. They crawled over the deck, hand over hand clutching the rope net, towards the helicopter. It was a bizarre sight and the thought did cross my mind that I must be a madman to not only have such a job but also to be enjoying the challenge!

We filled the cabin with rig crew not having any concerns about the number of seats available as one is permitted to ignore the Air Navigation Order when in a life or death situation. We did, however, still have to pay regard to the overall weight so as not to over-stress the aircraft. With such a wind strength there was no performance problem. We flew the relatively short distance to a nearby rig and dropped off our passengers before returning for a second load.

It was now time to return empty to dry land so the navigation issue came to the fore. Fortunately for us the centre of the deep depression, which was causing the extreme wind speeds, was moving rapidly and with this movement the direction of the wind was also changing. By the time we had completed the emergency evacuation, the wind direction no longer posed an insurmountable ground speed problem for the return to Sumburgh. So, having refuelled at the last rig, we abandoned the plan to fly on to Norway and returned to Shetland instead.

I was very pleased to receive a fuller explanation of the events surrounding this incident from Bob Worrall, who was working as an engineer for Shell at the time. His account, which includes a fuller history of the rigs in question, appears at the end of this section of the website. It is well worth a read, particularly as it provides some details on the problems facing our customers, the oil exploration industry and the formidable challenges they faced and continue to face in operating in extreme weather.

TRANSCRIPT OF ARTICLE FROM ESSO AIR WORLD – 1975 [with slight editing]

Article originally published in Esso Air World and reproduced here courtesy of ExxonMobil.

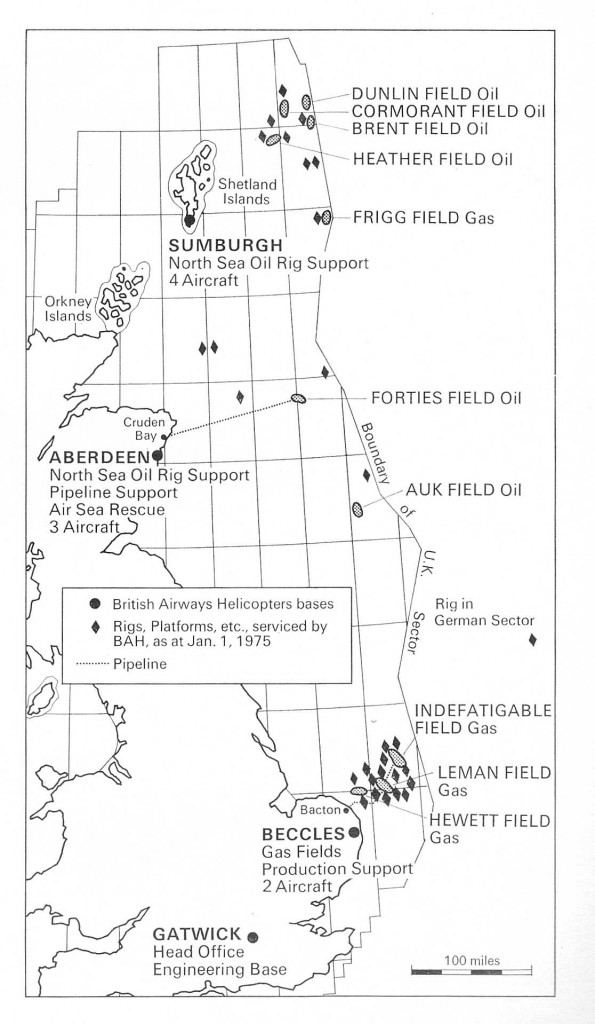

British Airways Helicopters serves the North Sea gas and oil fields

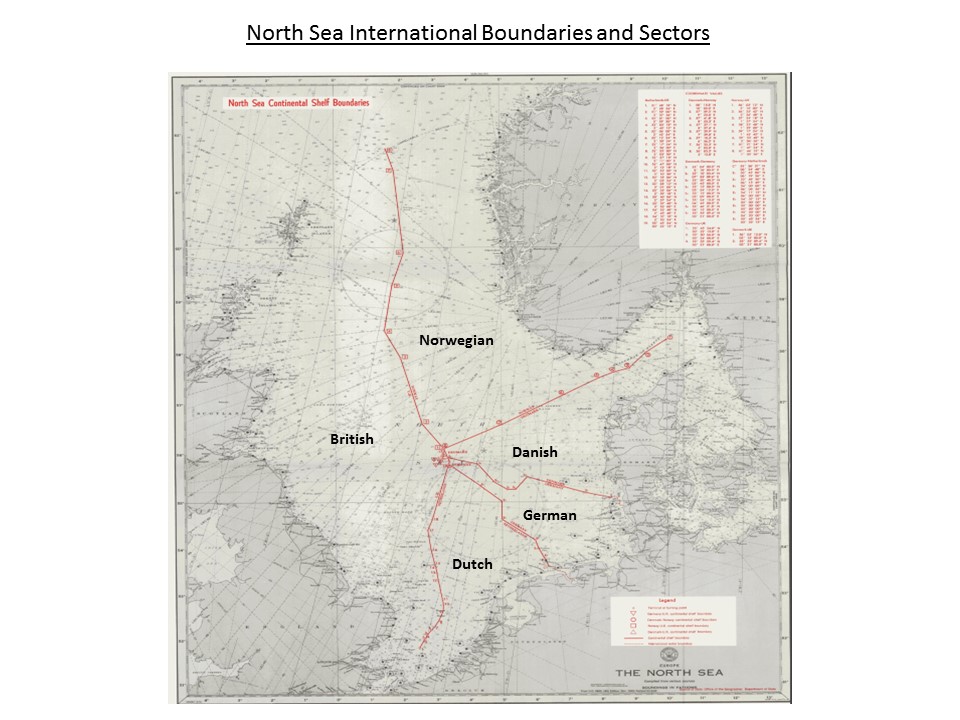

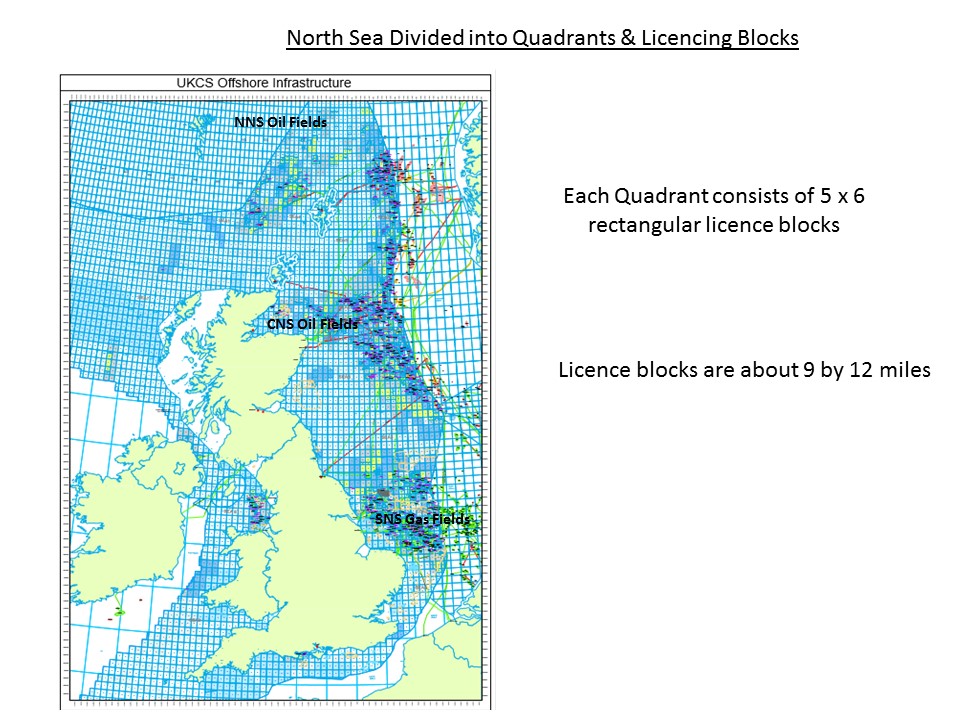

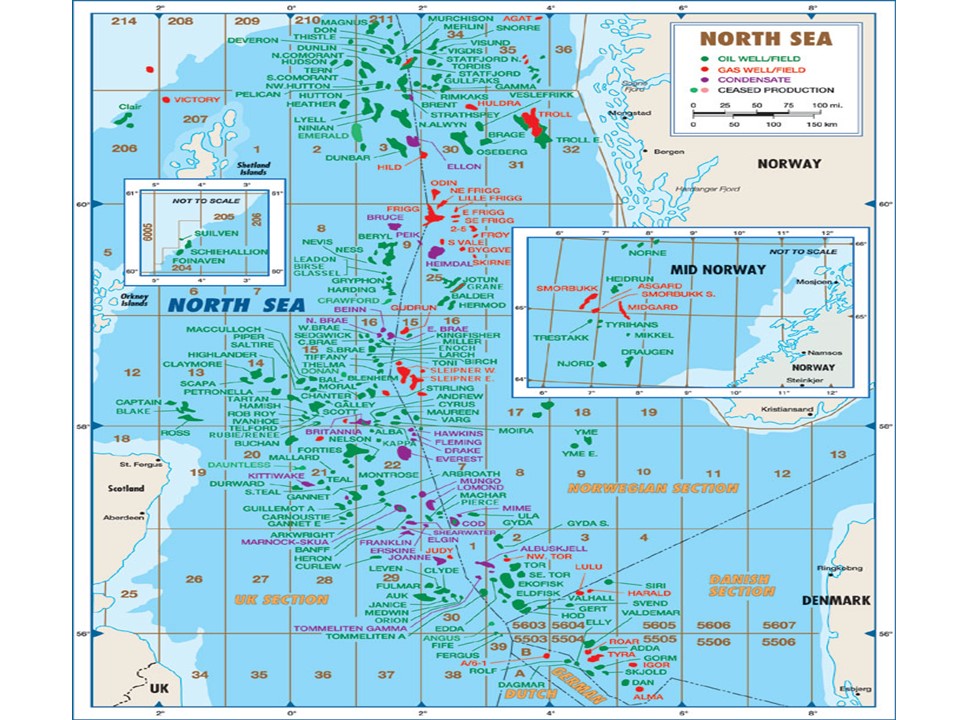

British Airways Helicopters, which has a history dating back to 1947, started servicing rigs in 1964 when, after the discovery in 1959 of huge natural gas reserves near the Dutch town of Slochteren. drilling started in the North Sea off the east coast of England. Later, when promising oil-bearing rock formations were located under the North Sea oil” the east coast of Scotland and to the cast and north-east of the Shetland Islands, and drilling started there. BAH became active in this area, too. Today, there are some twenty-eight to thirty drilling rigs and 41 production platforms in the British sector of the North Sea, the majority in the southern area. The rigs are mobile and arc constantly being moved; the platforms are permanent structures, and most of them arc or will be connected to the shore by pipeline. These installations are owned by or leased to some 16 major oil companies and other organisations either individually or under partnership agreements. Of these companies, Esso Shell. Burmah, Total. Phillips. Occidental, Unionoil and North Sea Sun Oil have contracts with British Airways Helicopters involving the regular servicing of up to thirty North Sea installations. The discovery of natural gas under the North Sea has already had a profound effect upon the British economy. One field is yielding 1-5 thousand million cubic feet a day; another has a potential output of 600 million cubic feet a day. Three other fields are contributing their quotas to the massive total, and more fields have yet to be brought into production. Gas consumption in the United Kingdom has increased threefold since natural gas started coming ashore, and over ninety per cent of the demand is based on North Sea supplies. Map shows location of main oil and gas fields in the UK sector of the North Sea, and the bases and servicing locations of BA Helicopters, which also operates a helicopter passenger service between Lands End, Cornwall, and the Isles of Scilly. * Crude oil from the British sector of the North Sea will start coming ashore during 1975; analysis of samples taken from the wells prove that the quality is equal to and in some characteristics better than Middle East oil. Some of the wells have reserves that promise high outputs over long periods; one alone has an estimated production capacity of 22 million tons a year. Geological surveys have located typical oil-bearing rock formations in close proximity to the region already explored, and the presence of oil has been proved several hundred miles to the south-west, off the west coast of England in the Irish sector of the Celtic Sea. Oil companies secure drilling rights by buying a lease of one or more of the blocks (each covering about 100 square miles) into which the North Sea (and other offshore waters) have been divided by the governments of the various countries with territorial claims on them. Four rounds of allocations in the UK offshore area have so far been made by the British Government (in 1964. ’65. ‘70 and ’71/72) and another is expected to be made shortly.

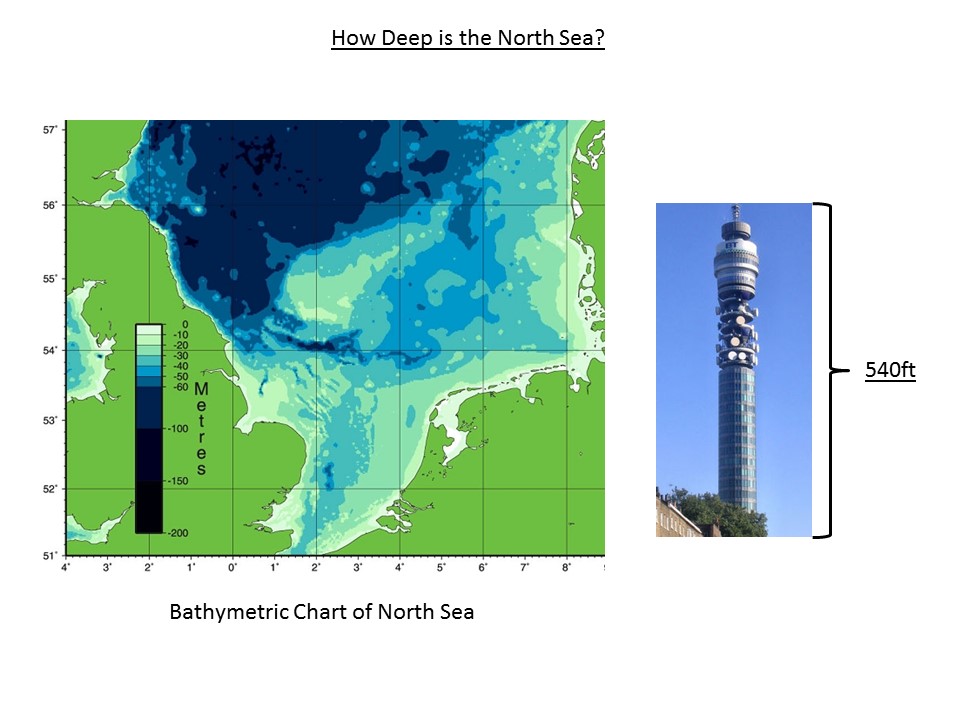

BAH’s servicing operations

British Airways Helicopters’ principal base for the natural gas fields is at Beccles. Norfolk; its operational bases are at Lowestoft and Yarmouth. In Scotland, it operates from Dyce Airport. Aberdeen, and in the Shetlands from Sumburgh. A possible future base is the island of Unst. 82 miles north of Sumburgh. On average, the distance to the offshore installations is between 90 and l(X) nautical miles, but at times (lights to points 180 nautical miles out have been made. The BAH fleet maintained at Beccles consists of one Sikorsky S-6IN and one Bell 212; the Dyce Sumburgh fleet is made up of eight Sikorsky S-61 Ns. Two twin-turbine-engined versions of the widely-used Sikorsky S-58 piston-engined helicopter bought in Germany and being converted by BAH at its main base at Gatwick, Surrey, will join the fleet in February or March. 1975, as will, later, three more S-61Ns now on order. Four Westland 656 (civil Sea Kings) may be added to the fleet in 1976. All types are equipped for day and night operation. S-61 Ns carry up to 22 passengers to the rigs, the S-58 up to 16 and the Bell up to 14. The crew consists of two pilots and a crewman. The number of passengers and the amount of cargo carried by each type depend upon the distance to be flown. Typical figures for the S-61 Ns are 12 passengers to rigs 180 nautical miles distant; 22 passengers to rigs 80 nautical miles offshore. Helicopters do not normally refuel at the rig, although fuel is available for use in an emergency. They must therefore leave base with enough fuel for the out-and-back trip and reserves for diversion to an alternative base in case their own is closed by weather or other cause. Normally the Scottish “alternate” is Kinloss or Inverness, but in some circumstances it could be Bergen in Norway. Customarily, BAH makes about live flights a week to each rig but schedules are liable to be varied for operational or other reasons. In addition, one helicopter is on standby duty, with its crew, to meet emergency calls—for instance, to bring ashore an injured rig crewman or to rush urgently needed spares out. Killer weather Weather in the North Sea is notoriously unpredictable and wide-ranging. It can be as placid as a mill pond one moment and tormented by hurricane force winds the next, piling up waves 100 ft. high. Fog and mist sweep over it without warning, and rainstorms of almost tropical intensity can hit the area with devastating violence. Below the surface, tidal currents flow with destructive power and are a source of hazards unsuspected by those unacquainted with them. Several of the rigs brought in from calmer waters when natural gas and oil drillings started were wrecked almost upon arrival; their stability and structural integrity were unequal to the North Sea’s testing stresses. These, in conjunction with the deep waters of the more northerly latitudes, have swung the design and building of rigs and platforms into a new orbit and led to the production of structures far larger than any previously built for offshore fields. One now under construction for Esso Shell, to give a production rate of 100,000 barrels a day and to accommodate 80 men will have a height of 755 ft. from the sea floor to the top of the drilling derrick, and weigh more than 40.000 tons. Similarly, the stormy environment and deep water— 200 metres or more—have led to the use of ships and semi-submersible vessels as drilling rigs. The semi-submersible vessel is fitted with large columns which, filled with water to the necessary level, give the rig the required degree of stability. Both types oil drilling rig have to be securely anchored so that no shift in position occurs whatever the forces acting upon them above or below the surface. Jack-up and submersible drilling rigs are supported by legs resting on the sea bed.

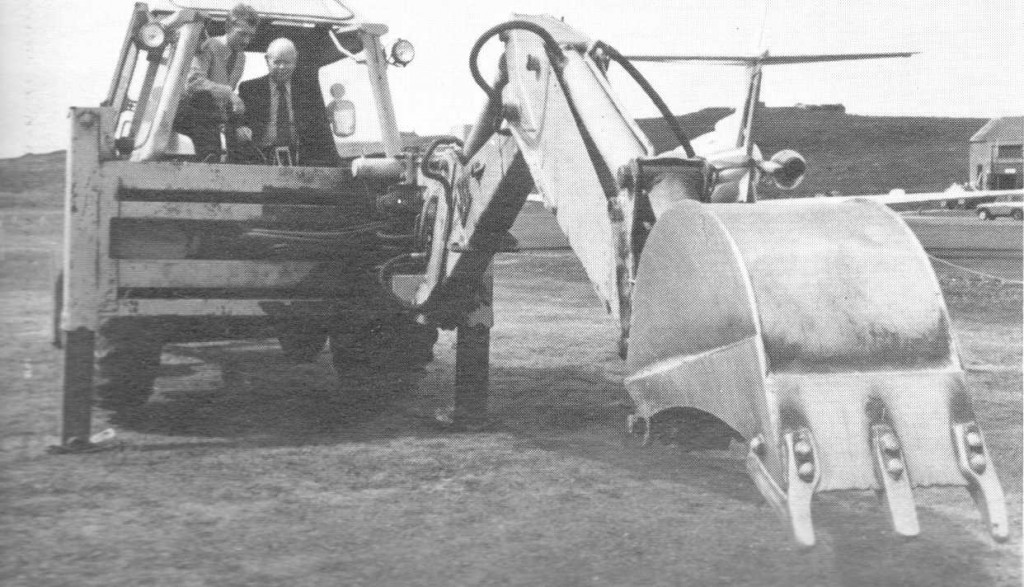

Capt. J. A. Cameron, Managing Director of BA Helicopters, breaks ground at Sumburgh Airport on the site of a new hangar, costing £400.000, which has since been completed.

Operational hazards

Rig servicing in good weather presents few dangers but good weather in the oilfield regions of the North Sea is less common than bad, and experienced pilots claim that anyone able to fly a helicopter in the oilfield belt can fly one anywhere in the world. All that can be done to reduce the hazards to a minimum is being done but it has to be remembered that the oilfields were a recent discovery and that developments did not follow precedents. Rigs appeared as if by magic and in their efforts to find and bring oil ashore the oil companies solved their problems as they met them, often against opposition from people who did not grasp the urgency of the work being done on land and at sea to safeguard and swell Britain’s oil resources. Helicopter pilots proved that, with available equipment—which included a Decca navigation system—they could find their rigs and return to base, thus fulfilling their part of the contract. At first, measures to lighten their task had to be foregone; but things are changing.

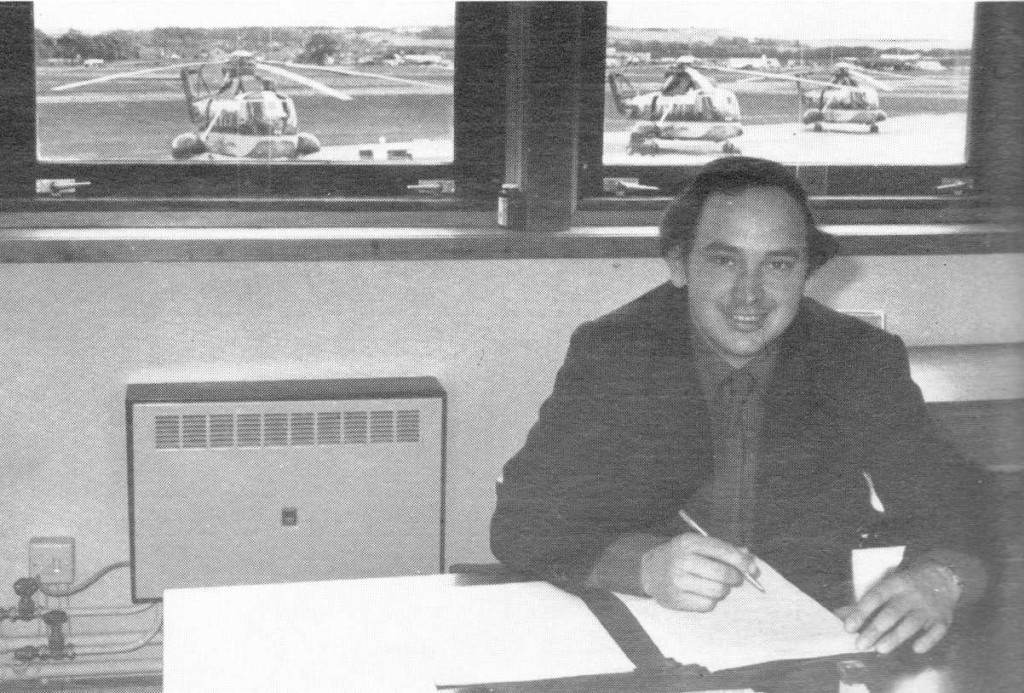

Capt. Mike Evans, BA Helicopters Flight Manager at Aberdeen. Outside, the bases’s three S-61s, with the airport terminal seen on the far side of the airfield.

Equipment

Some of BAH’s helicopters now have radar equipment designed to provide both weather and terrain mapping and a short-range sharp-resolution display for use in an airborne approach, or in search and rescue operations and other maritime reconnaissance roles. The equipment gives the pilot warning of weather hazards—storm clouds harbour turbulence and. often, icing conditions— along his route so that he can fly round them. It also enables him to locate a rig when visibility is bad and to make a “blind” touch-down. In due course, all the helicopters in the fleet will have the equipment. There is also a possibility that, later on the aircraft will be fitted with a modern radio guidance system which has already proved its worth in military operations. The equipment is likely to be installed experimentally during 1975 and, if found satisfactory, to be generally adopted the following year. Under the present routine, pilots report to base by radio every ten minutes while over the sea. An alert is raised if a ten-minute period passes without a report; a search and rescue operation is mounted if a second reporting period passes without word from the pilot. All the aircraft have flotation gear and. unless badly damaged, can remain afloat for a considerable time even in fairly heavy seas. Rig servicing operations associated with the natural gasfields oil England’s eastern shore were once under the threat of another hazard in addition to those posed by the weather. The danger came from low flying military aircraft which were in the habit of using the area for low-flying training. Consultation between the parties concerned led to the introduction of a safe and simple procedure: helicopters were allocated clearly-defined corridors between land-bases and rigs, and required to fly at heights between 750 and 2,500 ft. when over the sea. Military aircraft were required to fly either over or under the corridors. When cloud base drops below 1.500 ft., or visibility becomes less than three miles, low flying by the military is discontinued. The measurement of visibility and cloud base, and decision-making, is the responsibility of an organisation set up for the purpose. Similar procedures are to be adopted in other areas where low-flying military aircraft are. or might become, a hazard. Weather plays a big part in the operation of oil and natural gas rigs. No one would think of moving a rig for instance, if a violent storm were imminent. The industry relies largely upon national meteorological forecasts but the majority of operators also make use of a private forecasting service which covers nearly every continent and ocean. Nevertheless, as the head of this service once remarked: “North Sea weather is most capricious: it doesn’t know what it’s going to do next.” Needless to say, weather is of equal moment to the helicopter operators who service the rigs: their eyes are rarely oil’ the forecasts for their part of the world. The limitations on helicopter operations are a 200-ft. cloud base and 600 metres horizontal visibility.

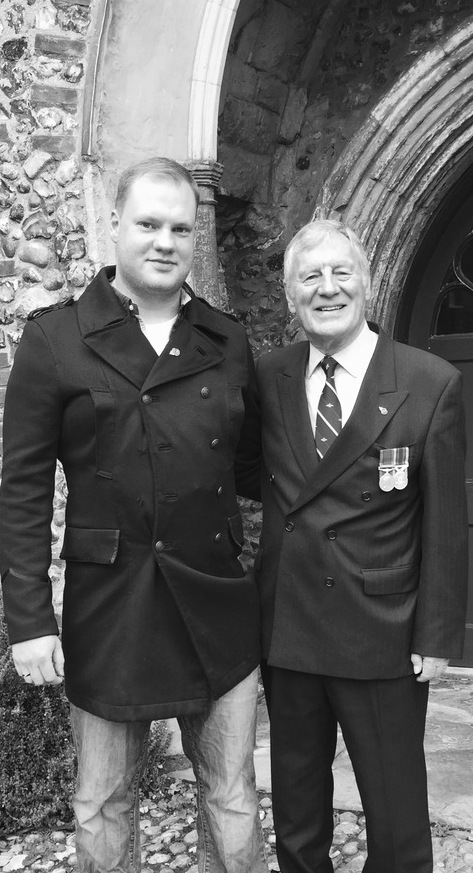

Captain Bill Ashpole (left), BAH Manager, Sumburgh, and Captain J W G “Jimmy” James, retired Chairman of BA Helicopters

Impeccable maintenance ensures round-the-clock availability for services which sometimes include calls from vessels like the old barge, shown riding a 50 knot gale, from which an injured crewman was lifted

When you’ve seen one wave you’ve seen ’em all. Rig crews wear immersion suits for their over-water flights.

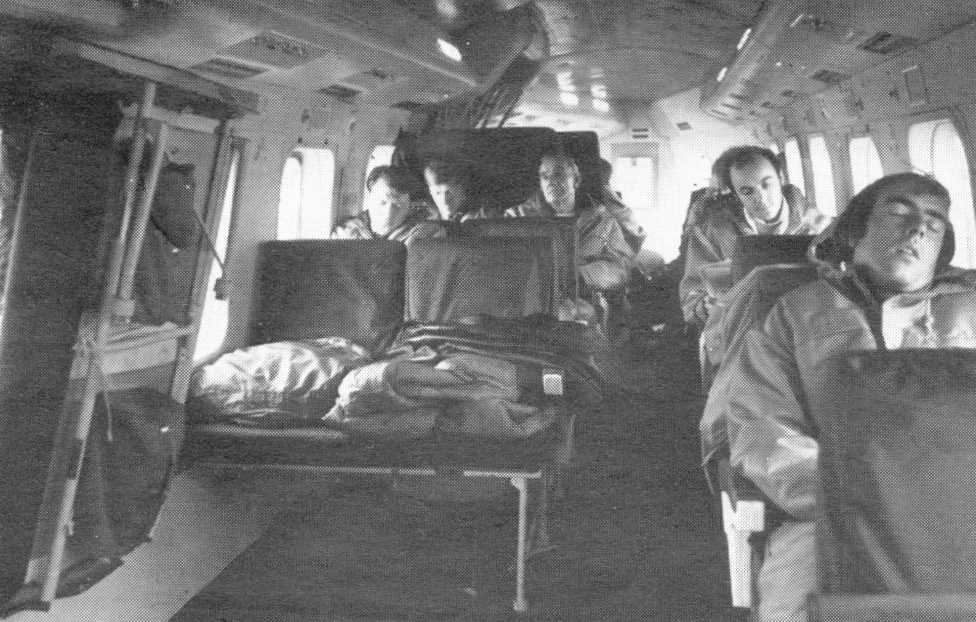

An S61, with Decca flight log prominent, approaches the Staflo rig where an injured crewman (lower picture) is taken aboard for swift transport to hospital.

Contracts and requirements

Contracts between helicopter operators and oil companies are basically simple, and consist mainly of a standing charge (which is more or less constant over the period of the contract) and a flying charge which depends upon the number of flying hours logged during a specified period. But, inevitably, variables creep in, and other factors come into the reckoning. An essential feature of service is reliability; if a helicopter is due at a certain time it must be there to the minute or the oil company might incur additional expense or charges. Furthermore, the service must be available twenty-four hours a day. Only an organisation with an adequate fleet of suitable aircraft, skilled crews in adequate numbers, efficient base support with competent and resourceful maintenance engineers can hope to survive in this fiercely competitive and exacting business.

An S61 leaves busy Sumburgh as another, in old BEA Helicopter markings, taxies in. Also seen is a BA Viscount and a Loganair Islander.

Air/Sea Rescue

British Airways Helicopters, apart from its commitments to the oil companies, has a contract with the British Government under which its aircraft and crews are available and equipped for seeking and rescuing the crews of ships, rigs and aircraft, and others, when they are in trouble. It receives, on average, one call a month and its crews have already earned high commendation for rescues that made heavy demands on skill and courage. They once took off 26 crew from a Scottish trawler that had gone aground. On another occasion, eight seamen were rescued from a foundered Polish trawler—four in a daytime operation and four in a tricky night rescue with a Force 10 gale blowing. Again at night, and in the teeth of vicious winds, two BAH helicopters from Sumburgh lifted 66 men to safety when their rig was threatened by floating wreckage from a rig destroyed by the storm. The full extent of the natural wealth under the North Sea and other waters surrounding the United Kingdom and Ireland is still not known. The commercial status of some of the wells already discovered has not yet been assessed; a number of wells have proved too small for production in the present economic conditions and have been sealed for tapping when, as seems inevitable, a growing scarcity of the precious commodity will make production a viable proposition. Clearly, the offshore oil industry around the UK coasts will for many years be in need of helicopter services – services which British Airways Helicopters, among others, will continue to provide.

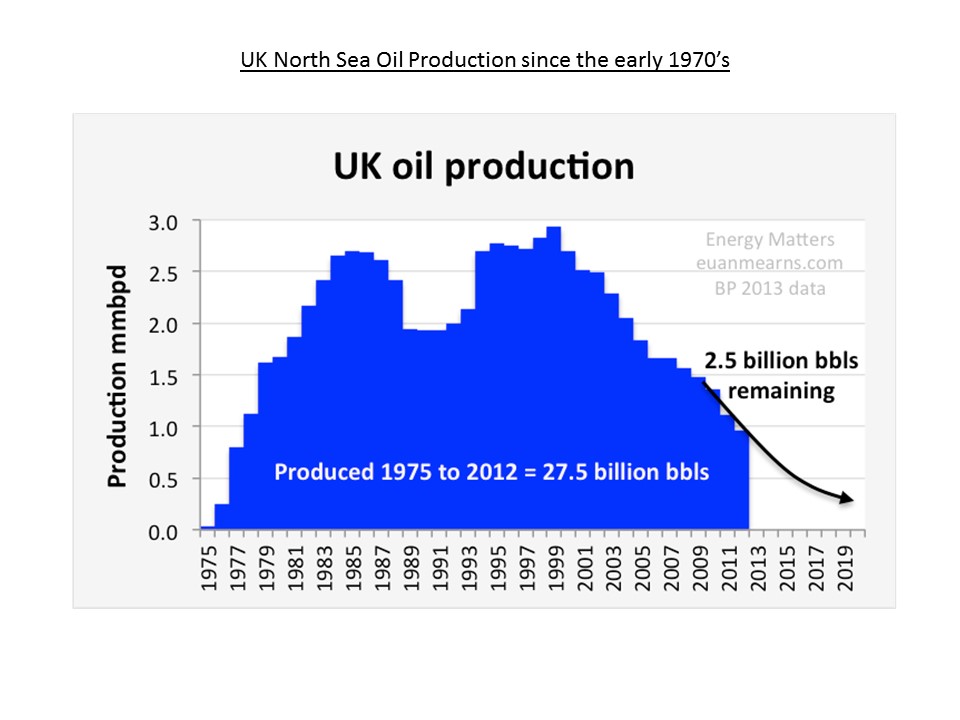

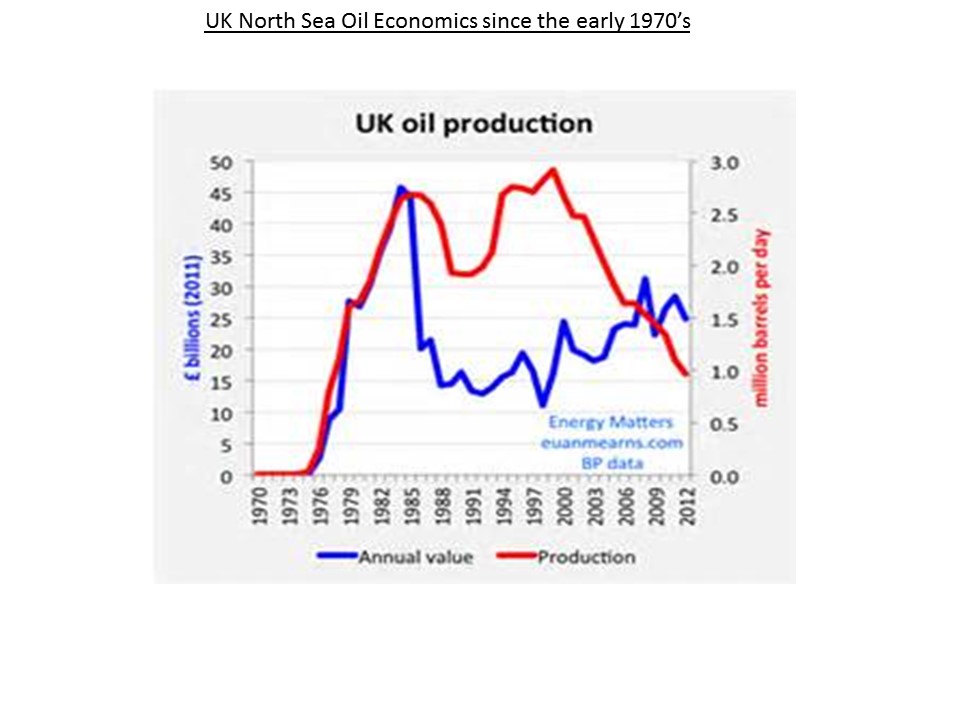

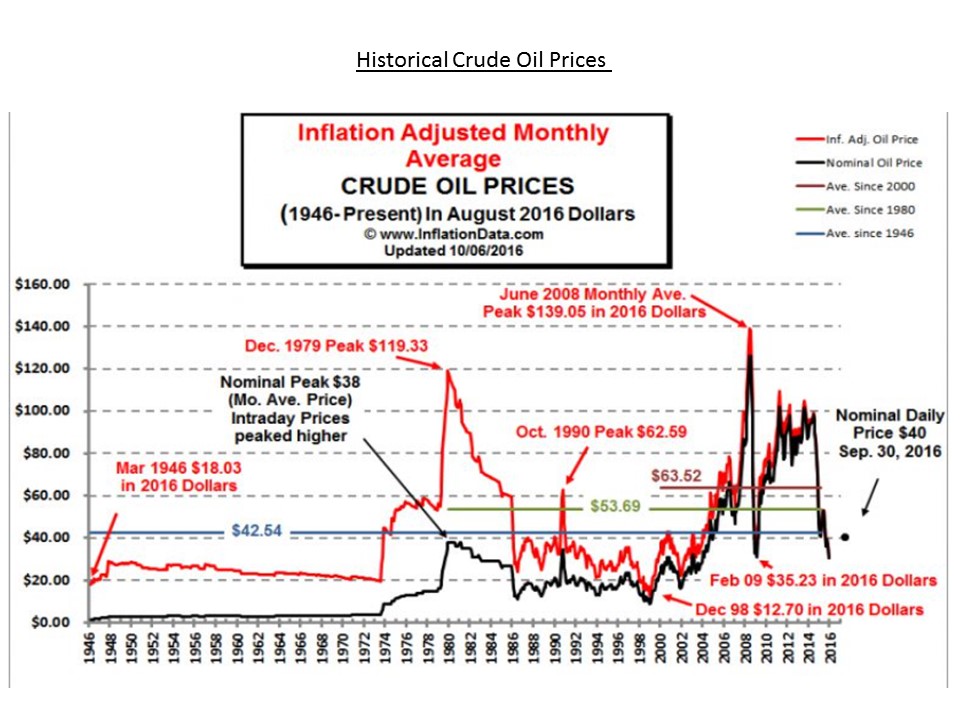

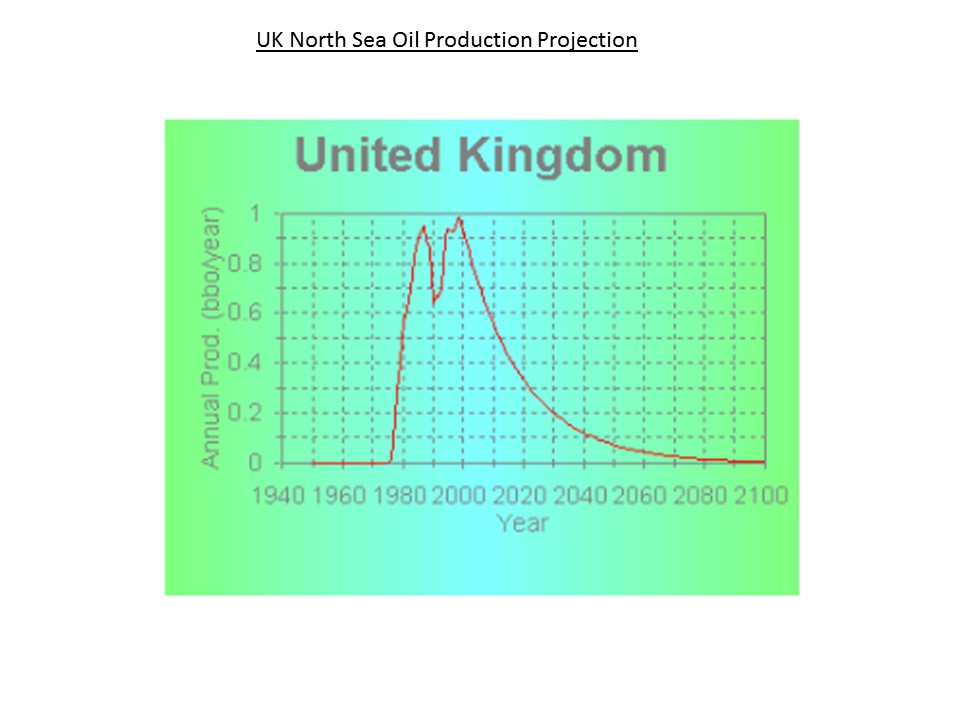

A few pages about the development of North Sea oil –

These were provided by Christopher Samson, a fellow member of our local Jaguar Enthusiasts Club who worked as a geologist for many years in support of the oil industry.

Oil & Gas Fields and Wells in the UK North Sea

The following interesting article was kindly supplied by Robert (Bob) Worrall who was a young engineer working for Shell in Lowestoft (1971-2) and Aberdeen (1972-5). For a while he worked on Staflo

This article gives an oil company perspective and rig details which can be read in conjunction with the previous section “Flying in “extreme” weather conditions”

This describes the rescue of the skeleton crew of the Transocean III. The company Transocean was a partnership between Kerr-Magee (who owned Transworld Drilling) and several German drilling companies. The rig had just been built by Blohm+Voss in Hamburg (who built The Bismarck and the US Coastguard sail training ship Eagle). It was similar to Transworld 61. We (Shell) had the rig Sedco 135G in the next dock for modifications for three weeks in about September 1072 so I had seen Transocean III under construction.

From Hamburg Transocean III was towed to a fiord in Norway and then out to its first drilling location for Mobil on the Beryl Field on the UK/Norway boarder. Transworld 61 was anchored nearby. TO3 anchored up and then cracks developed in a tubular bracing. Most of the crew were evacuated to Transworld 61 which was anchored nearby. As the cracks developed and the weather got up the remaining skeleton crew were evacuated by you to the TW61 as described below. I think this was a superb piece of airmanship.

The good folks in Oklahoma, Transocean’s HQ, became concerned that the rig with no crew might be boarded by a tug boat crew who would claim salvage. The following day Dieter Eickleburg, the rig manager of Transocean III, and Bob Deharsh the manager of TW61, flew out in a Norwegian helicopter, saw the rig was still afloat, and flew to Transworld 61 to refuel before landing on Transocean III. When they got back the rig had capsized and sunk. If they had been a few minutes earlier they would all have been catapulted off the deck and killed. One hull was floating around the North Sea for months and ended up in Northern Norway. Dieter, who had met a couple of weeks earlier in Stavanger, and myself became good friends and professional colleagues and worked together on numerous projects until he retired in 1986.

For the technically minded. An oval access hole had been welded in the tubular bracing during construction. This had been welded up. The cracks started at the weld. It was a lousy design of rig. I had worked on the Transworld 61 the previous summer in the Celtic sea.

On the article from “Esso Air World”. Exxon were partners with us offshore UK. We were the “Operator”. Both companies financed the investment 50/50 but we, Shell, actually spent the money with our customary gay abandon. Conventionally the partnership was referred to as Shell-Esso, and we were a major part to Exxon’s total investment at that time. I think this miffed Esso UK’s PR department. The picture is of Staflo, a rig actually owned by Shell.

The rig you evacuated was Transocean 3 (TO3) was basically the same design as Transocean 61 (TW61). They were the only two rigs built to this concept, which was a dead end. TW61 Was built in Japan in 1970. It had a drill ship hull and four diamond shaped floats, each underneath a 60-foot diameter leg. You can see the starboard float just breaking the water in the photo below.

The concept was that when under long distance tow it would be configured as a Drillship, and would tow faster than a Semi-Sub, as the longer hull had less wave drag. This would improve its competitiveness in the exploration drilling rig market at that time when successive jobs might be in different oceans.

This picture shows TW61 under long distance tow in drillship mode.

Once the rig reached the area of operations the dogs holding the one of the legs to the outrigger would be slid back (disengaged) and the diamond shaped floats flooded. The leg and float would sink to a total draft of 90 feet and the upper dogs would be engaged. The leg (and outrigger underneath) would then be locked into position. A large number of wedges were inserted between the circular leg and a tapered ring built into the outrigger or hull. These were hammered down with a large sledge hammer. These wedges locked the leg in position and transferred the horizontal forces and bending moments from the leg to the outrigger. There may have been two sets of wedges separated by say 20-30 feet vertically. The process was repeated for the other three legs, and the rig then de-ballasted to 60 feet draft, which was the normal operating condition. The rig would then be towed to its drilling location, and that is the configuration when you landed on it all those years ago.

The rig had no bracing between the diamond shaped floats and the hull, so the bending moments at the top of the leg and the stresses on the outrigger were much greater than with a conventional design of semi-sub. Think of the Staflo and Sedneth 2 which were of the same vintage, also at 60 foot draft, but with 20 columns and four hulls, and lots of diagonal bracing. The TO3/TW61 were much weaker structurally than most other rigs.

The later rigs such as the Sedco 700 series floated at 80-foot draft and had much less motion in big waves. The Staflo/Sedneth 2 had natural periods of 16 seconds, i.e. in 16 second period swells the vertical movement of the heli-deck was the same as the waves. At the time they were designed no-one imagined that we would try to operate in 16 second period waves. The S700 natural heave period was 23 seconds, so it moved much less in big seas.

The picture shows the rig TW61, most probably in the Bay of Biscay, on tow from Shell Spain (San Carles de la Rapita on the Mediterranean Coast) to Bantry Bay in SW Ireland in mid-1973. It was taken by the Master of the Wassertor, a 4000 HP German Supply Vessel which was towing. The master was probably Jan Hansing, or he may have been the Tow-Master on the rig. You can just see the port diamond shaped float of the rig breaking water.

I recognize the photo as Dick Kidd, Shell head of transport in Aberdeen had a copy on his office wall. Dick was also responsible for contracting BEA Helicopters, so you may have met him. He had a small wingspan handlebar moustache and glasses.

After the tow from Spain, John Bonstra the Shell Company Man/Tool-pusher and myself joined the TW61. We were in Bantry Bay which sheltered water with a depth of 120 feet. Once anchored the rig crew commenced unlocked the dogs on one leg and started to ballast the diamond shaped leg. John observed an 18” long open crack flexing in one of the legs. He turned to me and said “I am not an Engineer, but that does not look right.” We then spent 10 days welding up 198 cracks in the legs. We then towed the rig onto location in the middle of St George’s Channel, where it drilled one well before going to Mobil Beryl, where you landed on it.

After much prodding the Transocean Rig Manager, Bob Deharsh, and Larry Kulman, the designer, told us the previous history of the rig. The rig had left the Shipyard in Japan and gone to South Africa; I think on the Mussel Bay prospect. They had unlocked the first leg in a 15-foot sea and the leg had been in violent up and down motion for several hours. In the top of each leg was a room with no windows which had a bunch of mercury manometers to measure water levels in each of the float tanks. A guy was in this control room to relay the readings by telephone. When they got him out after several hours of violent motion, much noise, and total darkness, he was reported to be somewhat disoriented. The rig then spent three months sheltered waters being fixed before commencing drilling. It only had 42 bunks when first constructed. Most North Sea rigs had 80-100 bunks. Extra accommodation, of a less desirable nature, was fabricated in some of the main hull ballast tanks. A year or two later TW61 left the North Sea. It was too small, moved around in a rough sea, and the Unions objected to the lousy accommodation.

This website has the history of early offshore oil rigs

https://petrowiki.org/History_of_offshore_drilling_units

Record of your rescue flights.

These dates fit in with my recollections. I landed in Sumburgh from the 135 G on a BEA Helicopters S61N on about Dec 28 1973. We had been in Norway and it was being towed to a Shell UK location. The Aberdeen firemen were on strike against Maggie Thatcher so we could not catch a DC3 to Aberdeen. We spent the night in the Sumburgh Hotel wrecking the bar in the process, and then were flown to Abe in an S61N. I then drove to Northumberland for a New Year’s Eve Party. I heard about TO3 going down about Jan 4.

TW58, which also handled some evacuees was a very old small rig which had come up from Nigeria. It was the floating production unit for the Argyle field for Hamilton Brothers, which produced the first oil in the UK sector. I remember Tony Benn turning the handle (somewhere in Teesside-Jet Petrol from ICI?) on TV. Later on, I visited it in about 1976 when I was working in London on the North Cormorant platform design.

After the TO3 sank the diamond shaped float and leg which broke off floated round the North Sea for several weeks, and must be mentioned in Admiralty “Notices to Mariners”. It eventually ended up going aground in Northern Norway. Dieter Eickleburg, the TO3 Rig Manager, told me that they discussed bombing it with the RAF, who said that it would be difficult.

I found this site which gives brief details and timing of the flights. At the bottom is a list of North Sea Helicopter crashes.

Bob Worrall

http://members.home.nl/the_sims/rig/transocean3.htm

Summary – Transocean 3

Built in Hamburg, Germany in 1973 for the Transocean Drilling Company, the Transocean 3 rig was reported as a ‘special self-elevating semi-submersible design’, modified for use in the North Sea. Late-December storms in 1973 prevented the new rig from being moved to its first drilling location for Mobil, so the rig was anchored in 342 feet of water about 100 miles east of Shetland.

Between 29 Dec 1973 and 01 Jan 1974, the rig suffered progressive structural damage resulting from the storm conditions, leading to the evacuation by helicopter of 38 of the 56 crew at around 1800 hours on 01 Jan 1974. The remaining 18 crew were then evacuated by 2300 hours on 01 Jan 1974. The crew were transferred to the nearby Transworld 61 and Transworld 58 rigs. Four tugs were on stand-by to tow the Transocean 3 to Norway for repairs, but continued bad weather sank the rig in the early hours of 02 Jan 1974 before this could be performed.

HSE documents from the UK state that a jackable leg broke away from the machinery house, leading to the subsequent capsize and later sinking of the vessel. Weather conditions at the time were winds of 21m/s with waves of 6m. A later report for the Department of Energy concluded that the failure was caused by the inadequate performance of rings of wedges which were used to transmit bending movements between columns and cross-girders (location not mentioned, presumably on the legs – editor).

Sources:

The Times (UK): 02 Jan 1974 ‘North Sea rig sinks after crew taken off’

The Times (UK): 20 Jun 1975 ‘Structural defects blamed for loss of rig’

HSE: Review of issues associated with the stability of semi-submersibles

Robert Worrall.. June 2020

A good article which sums up the start of BEAH/BAH in the Shetlands

I’m really enjoying the design and layout of your blog. It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to come here and visit more often. Did you hire out a developer to create your theme? Superb work!

discount michael kors yellow tote

[url=http://www.caballerolawoffices.com/discount-michael-kors-yellow-tote-p-7644.html]discount michael kors yellow tote[/url]

Thanks for your kind comment. No developer was used.

Bill Ashpole

Thanks for this wonderfull article, I will be showing to my father who is Captain John Marriner who flew from Shetland around this time from Sumburgh airport when I was a wee lass living there.

Hoping you may have remebered him. Fly the Flag

Hi Kate – thank you for your kind comments concerning the website. Hopefully, your father will find it interesting. I am about to update it with some maps and charts showing oil exploration from a geologist’s perspective. I don’t remember your father but I left Shetland in 1975 and he, and you, probably arrived after that time. If this is not correct then please put it down to my memory malfunctioning – happens when you are my age! My three children all reflect on their days in Shetland with fond nostalgia. I hope you do as well.

Best wishes

Bill Ashpole

Hi Bill,

I was a Radio Engineer based at LGW 1972-86 & worked all the Helicopters at all

the bases when required. I remember you well.

Your report was quite enlightening

I remember seeing one tree at Sumburgh & fishing very late at night for trout when it was still light

Thanks for the memories

Ken W

Hi Ken – Really good to hear from you after all these years and to learn that you are still around – so many of our former colleagues have, sadly, passed away. I had contact with Harvey Pole quite recently so know he is going strong. Yes – Shetland was different – could be breathtaking in its scenery but a terrible place for wind – the long summer days and the short winter nights. I hope you are doing well and enjoying life. Best regards Bill Ashpole

Bill, one of the above is from December 2017. It’s a great “blog” and brought back many memories. Also passed on to the family. Best wishes ,John Tindall (don’t laugh but BA pilot rtd!)

Hi John – great to hear from you again after all these years – the last time, I recall, was at Redhill when you flew a couple of my friends in a microlight! I had learnt that you became a captain in BA – very experienced engineer and pilot – that is some CV! Thanks for your kind comment on the blog. Please feel free to submit anything of relevance – interesting or amusing from your memory bank and I will insert with full acreditation. Best wishes Bill

Hi Bill- Do you remember me Drew Mullay ?

I used to baby sit your kids at Scatness.

Enjoyed flying with you .

Hope you are well .

Learned to fly the R22 later in life and also went for my fixed wing pilots licence

Hope to hear back from you.

Kindest regards

Andrew

Replied to privately.

Hi Bill

Peter Hill here, who used to fly the S58T’s out of Sumburgh. Was just visiting Pete Bramley today, will be 90 next March 21st, who asked if anyone knew the latest whereabouts of Mike Evans. Wondered if you might know. All the best

Peter

Hi Peter – great to hear from you after all this time and learn that both you and Pete Bramley are still around. Please pass my best regards to him and wish him well.

I do not know the whereabouts of Mike Evans – I have not heard of him at all since I left Airlink. I think he got a job in the Emirates but must have retired long ago. Stew Birt might know. I have his email if you need it.

Wishing you and yours good health and a long life.

Bill Ashpole

Thanks for replying Bill. Will pass on your regards to Pete Bramley and would appreciate Stuart Birt’s email address re: Mike Evans. Will let you know how I get in.

All the best

Peter

Replied to privately.

Hello Bill,

My name is Tony Buckley. You welcomed me to Shetland straight from the RAF in 1975 with wife, a baby and a toddler. After c. 6 weeks in the “Meadowvale” we were lucky enough to get the first of the BAH Sandbister houses, albeit without water or electricity.

Really enjoyed reading your very comprehensive and accurate description of those early days. I became part of the Training team along with Dave Humble and Steve Jowett, and we processed something like 70 new pilots before I left for Aberdeen in 1978.

Hi Tony – lovely to hear from you and learn that you are alive and kicking! Those were interesting days and I feel we can look back with some pride on what was achieved in spite of some difficult conditions – you mentioned the house without utilities as one such. I just had a reunion in a pub in Norwich with some notables whom I have not seen for around 40 years – Ian Morrison, Mike Fermor, Tony Ridley, and others. Don Huggett hoped to be there but was recovering from an operation. I find such occasions very moving! So many have passed away. We hope to have another get together soon so if you are living anywhere near Norwich just let me know and I will make sure you get the message. I hope this finds you and your family well. All the best for 2019. Bill Ashpole

Best Wishes again for a Happy and Healthy New Year.

Fascinating to hear the names you mentioned after such a long time, I did not know Tony that well, but Mike and I were trainers on the simulator in Aberdeen, Don and I were involved with the ill-fated Hong Kong – Macau shuttle for 18 months (I met up with him at an RAF Search and Rescue squadron reunion last year). Ian Morrison’s civil career and mine were intertwined for many years; firstly I bought Ian’s house in Spiggie, Shetland; we were very friendly during the Aberdeen years and then we were both in Brunei during my Shell Aircraft time. I would be delighted if you could pass on my email address to him and see if he would mind getting in touch (tonybuck11@gmail.com).

I am not living very close to Norfolk (back in my native North East England near Darlington), but if you have another get-together this year I would try very hard to get down for a touch of nostalgia.

If you are at all interested, my progression was RAF, BAH Sumburgh, BAH?BIH Aberdeen, Shell Brunei, Shell Holland (Ground tour), Chief Pilot Brunei, CAA Flight Ops Inspector, then Tony Buckley Aviation Services up to retirement.

Delighted that you took the time to reply and once again congratulations on such a well composed history of civil helicopter operations.

Kind Regards, Tony B

Dear Bill,

What a great suprise! I made a typo in Google and a link to your website came up, it brings back fond memories of an almost idyllic life, well, for the first few years of the BEA/BAH operation in Shetland, it did get a bit hectic after 1976. Well done for writing the site and keeping the Blog up.

Mike Evans is living in southern Portugal, I have his email if anyone wants it. Sadly Jim Booth died a couple of years ago, as did Steve Jowett. Has anyone any info on Dave Humble, I’ve tried to find him, last known living in Spain, but I’ve had no success. There are so many people who I would love to know where and how they are, we were a very happy, diverse bunch in the early and mid 70’s.

Regards

Dave

Replied privately

Hello Bill

Thanks for the articles – they bring back lots of great memories. I first came to Sumburgh in 1973 as an ATCO Cadet, when Les Isaacs was GM with Mick Bain his other ATCO, & Tam … , the Tels engineer. I stayed at the Meadowvale for my 4 weeks detachment, looked after by Maggie Harper ; being English & trying to decipher her Fraserburgh accent was sometimes difficult ! I dont have the exact dste but at some point in either August or September 1973, I recall you flew me to Sedco 135 & back on a fam-flight Mick had organised for me.

My next encounter with the North Sea was in January 1980, when I was posted to the Ninian Central in the East Shetland Basin. You may recall that IAL (International Aeradio) were providing an ATC service by then. As I understand it, Shell & Chevron wouldn’t play nicely together so two units were established, one for the Ninian field on the Central, the the other for everywhere else on Cormorant Alpha. Shetland Radar at Saxa Vord handed over traffic at the ‘gates’, our Ninian traffic usually transiting at 500ft to/from Unst, the rest 1000ft or above to/from Sumburgh, & later Aberdeen when Chinooks came along. Of course Bristows were the main operator for Chevron but the BAH connection was the S61, G-BEOO – that was our regular daily freighter.

The IAL Manager based in Aberdeen during my tenure was Chris Fitch & in 1982 he & I moved to Liverpool, saying farewell to the North Sea. In 1993 I moved to Prestwick, from where I retired in 2013 after 42 years in ATC.

Best wishes

Dave Mobbs

Bill,

I was a young engineer working for Shell in Lowestoft (1971-2) and Aberdeen (1972-5). For a while I was working on Staflo and I am sure I have been flown by you. Many thanks for the safe arivals.

These are some of my recollections, apoligies if I have got it wrong.

The section Flying in “extreme” weather conditions”

This describes the rescue of the skeleton crew of the Transocean III. The company Transocean was a partnership between Kerr-Magee (who owned Transworld Drilling) and several German drilling companies. The rig had just been built by Blohm+Voss in Hamburg (who built The Bismarck and the US Coastguard sail training ship Eagle ). It was similar to Transworld 61. We (Shell) had the rig Sedoco 135G in the next dock for modifications for three weeks in about September 1072 so I had seen Transocean III under construction.

From Hamburg Transocean III was towed to a fiord in Norway and then out to its first drilling location for Mobil on the Beryl Field on the UK/Norway boarder. Transworld 61 was anchored nearby. TO3 anchored up and then cracks developed in a tubular bracing. Most of the crew were evacuated to Transworld 61 which was anchored nearby.

As the cracks developed and the weather got up the remaning skeleton crew were evacuated by you to the TW61 as described below. I think this was a superb piece of airmanship.

The good folks in Oklahoma, Transocean’s HQ, became concerned that the rig with no crew might be boarded by a tug boat crew who would claim salvage.

The following day Dieter Eikleburg, the rig manager of Transocean III, and Bob Deharsh the manager of TW61, flew out in a Norwegian (?) helicopter, saw the rig was still afloat, and flew to Transworld 61 to refuel before landing on Transocean III. When they got back the rig had capsized and sunk. If they had been a few minutes earlier they would all have been catapulted off the deck and killed. One hull was floating around the North Sea for months and ended up in Northern Noway.

Dieter, who had met a couple of weeks earlier in Stavanger, and myself became good friends and professional colleagues and worked together on numerous projects until he retired in 1986.

For the technically minded. An oval access hole had been welded in the tubular bracing during construction. This had been welded up. The cracks started at the weld. It was a lousy design of rig. I had worked on the Transworld 61 the previous summer in the Celtic sea.

On the article from “Esso Air World”. Exxon were partners with us offshore UK. We were the “Operator”. Both companies financed the investment 50/50 but we, Shell, actually spent the money with our customary gay abandon. Conventionally the partnership was referred to as Shell-Esso, and we were a major part to Exxon’s total investment at that time. I think this miffed Esso UK’s PR department. The picture is of Staflo, a rig actually owned by Shell.

The Sumburgh Hotel. A few days before the valiant rescue I stayed there for one night with a returning rig crew. Our DC3 back to Aberdeen was unable to fly as the Aberdeen Airport Fire Department were on strike in sympathy with the coal miners. I remember it well, as it was the only time in my life I became an (unwilling) participant in a bar fight. The place was wrecked. The fight was started when our Canadian Electrician, got up to go to the restroom, as he had consumed several pints of beer. Regretfully he stumbled and fell on top of the rather attractive wife of a BEA helicopter mechanic………………

The 19 of us flew back to Aberdeen on a S61N chopper the following day. Choppers don’t crash at high speed so no firemen are required.

I eventually retired from Shell in 2005, worked in Switzerland (Google Basel Earthquake…it was only 3,2) for a coupe of years and am now in Florida

Thnks very much for your narritive. I found it fascinating

Bob Worrall

Bob – what a very interesting account. I was particularity delighted to receive your message as I have tried on several occasions to find out more details of this incident. Yo have provided an enormous amount of information. Do you have the actual date of the flights by our three helicopters to the Transworld 61? I wanted to obtain a synoptic chart from the Met office depicting the isobars that night. Unfortunately, I had entrusted my logbook to someone else to fill in my flights and, probably because the flight was in the early hours of the morning, I cannot find it, for certain, in the logbook.

As you account is so good, I would like to make reference to it in the section “Flying in extreme weather conditions” so that readers can look it up in the Comments section.

I was reminded of the Sumburgh Hotel by your incident. Someone likened it to the bar scene in the first Star Wars film!

I hope you are enjoying life in Florida -not a bad place to which to retire, if indeed you have.

Wishing you and yours good health and thanks again for the article. Let me know if you remember the date.

Bill